IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 20 Aug 2013

Burundi- Reduce Neonatal-Mortality by Preventing Maternal Malaria

This guest blog has been re-posted from The blog by Chioma Anigbogu who is in our course, Social and Behavioral Foundations of Primary Health Care.

Malaria continues to severely burden many Sub-Saharan countries, including the nation of Burundi. In Burundi, 78% of the country lives in high or low transmission areas. Â In this population, pregnant women are at greater risk of experiencing spontaneous abortions, low birth weight, neonatal deaths and even anemia due to malaria. Â However, researchers have found that prevention treatment (Intermittent prevention therapy or IPT) during pregnancy can significantly reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity.

The WHO has a three-pronged recommendation for the prevention of malaria, including IPT, distribution of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) and proper management of disease. Burundi adopted an ITN policy in 2004 and has many in-country and international programs that distribute ITNs. Burundi even reports 100% treatment coverage for tested malaria cases. However, unlike some other African countries, Burundi has not adopted an IPT policy for malaria, leaving pregnant women and children extremely vulnerable.

In 2011, the government of Burundi (GOB) developed the Global Health Initiative, in partnership with international organizations, that is aimed at reducing maternal, neonatal and child health disease. The GHI holds a specific tenet regarding the “prevention and treatment of malariaâ€. In 2009 Burundi also received funds from the US- Agency for International Development (USAID) to complement already existing malaria activities. These activities sometimes include IPT but there is no formal requirement or enforcement of the treatment. WHO suggests that confusion amongst health workers may contribute to the lack of recommendation for this preventative treatment. A national policy that is developed and properly implemented would train health officials and workers in assuring that this treatment is integrated to the provision of services for women.

It would increase the overall health of the country and further bolster the work of other organizations such as Doctors without Borders and the Canadian Red Cross who are invested in Burundi’s malaria management. Adoption of this policy in Burundi will also reduce the negative impact of malaria, and may even reduce overall health spending by helping to maintaining better health for mothers and neonates.

In order to contribute your voice, leave a comment for the USAID (who works directly with Burundi), encouraging them to work with the Burundi government to adopt an IPT policy.

Photo Credit: Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders)

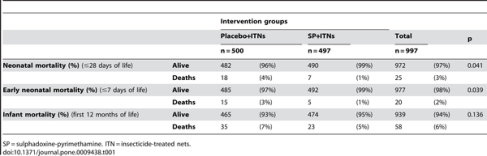

IPT Table:Â http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0009438

IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy &Surveillance Bill Brieger | 11 Nov 2012

Low prevalence of placental malaria infection among pregnant women in Zanzibar: policy implications for IPTp

A Poster Presentation at the 61st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 11-15 November 2012, Atlanta.

Marya Plotkin1, Khadija Said2, Natalie Hendler1, Asma R. Khamis1, Mwinyi I. Msellem3, Maryjane Lacoste1, Elaine Roman4, Veronica Ades5, Julie Gutman6, Raz Stevenson7, Peter McElroy8 – 1Jhpiego, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, United Republic of, 2Ministry of Health Zanzibar, Zanzibar, Tanzania, United Republic of, 3Zanzibar Malaria Control Programme, Zanzibar, Tanzania, United Republic of, 4Jhpiego, Baltimore, MD, United States, 5University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, United States, 6Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and President’s Malaria Initiative, Atlanta, GA, United States, 7United States Agency for International Development, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, United Republic of, 8Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and President’s Malaria Initiative, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, United Republic of

Efforts by the Zanzibar Ministry of Health to scale-up malaria prevention and treatment strategies, including intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp), have brought Zanzibar to the pre-elimination phase of malaria control. P. falciparum prevalence in the general population has been below 1% since 2008 and the diagnostic positivity rate among febrile patients was 1.2% in 2011.

Zanzibar implemented IPTp using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in 2004 when malaria prevalence exceeded 20%. While coverage among pregnant women is low (47% received two doses SP), the value of this intervention in low transmission settings remains uncertain. Few countries in Africa have confronted policy questions regarding timing of IPTp scale-down.

Zanzibar implemented IPTp using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) in 2004 when malaria prevalence exceeded 20%. While coverage among pregnant women is low (47% received two doses SP), the value of this intervention in low transmission settings remains uncertain. Few countries in Africa have confronted policy questions regarding timing of IPTp scale-down.

We designed a prospective observational study to estimate prevalence of placental malaria among pregnant women with no evidence of receiving any dose of SP for IPTp during pregnancy. From September 2011 to April 2012 we enrolled a convenience sample of pregnant women on day of delivery at six hospitals in Zanzibar (three in both Pemba and Unguja).

Dried blood spots (DBS) on filter paper were prepared from placental blood specimens. DBS were analyzed via polymerase chain reaction indicating active Plasmodium infection (all species). To date, over 1,200 deliveries were enrolled at the six recruitment sites (approximately 12% of total, range: 8-26%). Two (0.19%; 95% CI, 0.05-0.69%) of 1,046 DBS specimens analyzed to date showed evidence of P. falciparum infection. Both were from HIV uninfected, multigravid women in Unguja.

Birth weights for both deliveries were normal (>2500 g). Data collection will continue through the peak transmission season of May-July 2012. The very low prevalence of placental infection among women who received no IPTp raises policy questions regarding continuation of IPTp in Zanzibar. Alternative efforts to control malaria in pregnancy in Zanzibar, such as active case detection via regular screening and treatment during antenatal visits, should be evaluated.

IPTp &ITNs &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 28 Jun 2012

Malaria in Pregnancy: Learning from Global and Regional Programs

Malaria in Pregnancy: A Solvable Problem—Bringing the Maternal Health and Malaria Communities Together – a meeting in Istanbul organized by the Maternal Health Task Force, Harvard University.

Malaria in Pregnancy: A Solvable Problem—Bringing the Maternal Health and Malaria Communities Together – a meeting in Istanbul organized by the Maternal Health Task Force, Harvard University.

Take Away Messages from Day 2 Presentations by James Kisia, Kenya Red Cross.

The first roundtable of the second day was moderated by Koki Agrawal of MCHIP. Key lessons were the need to strengthen ANC as a platform for IPTp and ITN delivery. We need to address how to get the ANC systems funded—not just the interventions. Dr Agarwal challenged the panel to examine how to better measure processes that facilitate the delivery of care and to consider taking service beyond the walls of the health facility… and building stronger linkages between the facility and the community. We must develop indicators for quality of care and integration of programs

Viviana Mangiaterra of WHO explained that there are systematic issues in MIP; little investment has been realized (Global Fund has been doing most of the funding and is currently getting reorganized to increase technical guidance on MIP interventions as well as delivery mechanisms). There are different entry points – each provides opportunities for improvement in continuum of care. We must strengthen at different levels (for ex: CCM) to influence process

Mary Hamel of CDC demonstrated variations and contradictions in WHO guidelines on IPTp which can translate to country-level and implementation level confusion. She explained that, in the face of confusion, health workers are likely not to want to do harm—and, hence, do nothing. A simple clarifying memo from the Ministry of Heakth to health staff can help reach the desired level of IPT uptake.

Susan Youll of PMI talked about major challenges of poor data availability, stock outs. SP is not included in “tracer†commodity; not tracked in the same way other essential drugs are tracked. She discussed the negative effects of hidden fees for ANC services and the impact of this on IPT uptake and encouraged promoting the role of community to create demand.

Elena Olivi from PSI said of Nets that —“funding, funding, funding!†– is the answer. She reminded us of the overwhelming evidence that the biggest contributor to decrease in malaria cases was nets and cited by World Bank study on Kenya. Net delivery mechanisms are established and known. Nothing fancy about it! ANC is one of many platforms to deliver nets. She cited an example of nets treated like medicine with a prescription, enabling better tracking and forecasting. Behavior not an issue; knowledge about nets not a barrier to usage. There are technical champions for nets (PSI). The Advocacy community has not recognized the severity of the funding crisis—and lack of incentive to make bednets truly longlasting!

In conclusions, international partners have found that malaria in pregnancy cannot be controlled without basic resources and commodities. Advocacy is needed.

IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 20 Apr 2012

Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy – Maintain the Intervention

Intermittent Preventive Treatment of Malaria in Pregnancy (IPTp) as part of antenatal care (ANC) is a key malaria control strategy in areas of stable falciparum transmission. Growing resistance of parasites to the drug used for IPTp, sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) have led malaria program managers to wonder whether they should stop IPTp. Information presented at the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership’s Malaria in Pregnancy Working Group meeting this week in Kigali, Rwanda, cautions about not throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Peter Ouma of the Kenya Medical Research Institute/US Centers for Disease Control & Prevention and a member of the Malaria in Pregnancy Research Consortium shared research that showed continued value of SP for IPTp. Peter shared data on the importance of three doses of IPTp on reducing placental parasitemia, the condition that causes inter-uterine growth retardation and is especially helpful for primi- and secundi-gravidae.

Three IPTp doses is within the context of the recommended “at least two†doses recommended for pregnant women after quickening in stable transmission areas. In fact some countries like Ghana already recommend three.

Peter also advocated for more attention to SP drug quality. Most of the donors focus attention on quality approval processes for the treatment drugs – artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) – but many countries buy their own SP from various sources. Thus continued use of IPTp with SP should be linked with drug quality control to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Of course people recognize that SP will eventually need to be replaced. Various individual and combination drugs are being tested. Richa Chandra of Pfizer presented information on one such preventive treatment – Azithromycin and Chloroquine FDC (AZCQ). Most interestingly, AZCQ was found to be synergistically effective even with parasite strains that were resistant to chloroquine.

Should research favor roll out of AZCQ, practical planning and costing issues would need to be addressed. Like other drugs being tested, this combination would need to be given for three days unlike the one-time-only treatment dose of SP. Richa stressed the importance of community engagement if adherence to this 3-day regiment is to be achieved.

There was fear from the programmatic side that early cessation of IPTp within ANC would create a programming gap, such that when a replacement drug or combination comes along, it would be difficult to reintroduce IPTp into the ANC routine. But continued IPTp with SP is more than a placeholder; scale up and maintain IPTp programs in our high transmission countries will still save lives.

IPTp &ITNs &Malaria in Pregnancy &Monitoring Bill Brieger | 19 Apr 2012

Sustaining Gains or Retracting Progress

Currently the Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership’s Malaria in Pregnancy Working Group is meeting in Kigali, Rwanda. Seven country teams present have presented their progress and challenges, including most recent information on coverage/use of long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs) and intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp). Other working group members have also presented coverage data from other countries.

Two main challenges emerged. First, for the most part stable endemic countries that are using IPTp and reporting recent levels of coverage for this and for LLINs are hardly reaching the 2010 RBM targets of 80%. The second challenge is that some countries have actually recorded recent drops in IPTp coverage.

Two main challenges emerged. First, for the most part stable endemic countries that are using IPTp and reporting recent levels of coverage for this and for LLINs are hardly reaching the 2010 RBM targets of 80%. The second challenge is that some countries have actually recorded recent drops in IPTp coverage.

Group members presented experience and research that help explain these challenges. Coverage with the minimum two doses of IPTp has been hampered by the following:

- periodic stock-outs of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) supplies

- complexity of the steps involved in providing IPTp properly as directly observed treatment at antenatal clinic

- poor dissemination of national malaria in pregnancy (MIP) policies and guidelines

- inconsistencies in IPTp guidelines between malaria control and reproductive/maternal health service units

- lack of coordinated planning between those two units

The second problem, as seen in the chart to the left may be due to the above mentioned factors, but also imply more serious health systems problems. SP has become a forgotten step-child in the essential medicines portfolio. Once reduced treatment efficacy was observed with SP, countries began switching to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) for case management. SP was, according to meeting participants, still efficacious for prevention, but the formal health sector has not always responded by keeping it in stock.

The second problem, as seen in the chart to the left may be due to the above mentioned factors, but also imply more serious health systems problems. SP has become a forgotten step-child in the essential medicines portfolio. Once reduced treatment efficacy was observed with SP, countries began switching to artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) for case management. SP was, according to meeting participants, still efficacious for prevention, but the formal health sector has not always responded by keeping it in stock.

In fact the private sector still stocks SP because customers demand this cheaper alternative to ACT, even though such unregulated use may add to the problem of parasite resistance. Also donor programs, recognizing that SP is relatively cheap, often rely on endemic countries to purchase their own SP stocks, which some are reluctant to do.

IPTp saves lives in countries with stable malaria. The pregnant woman herself may not ‘feel’ the results of malaria that is concentrated in her placenta, but the fetus is deprived of nourishment and may be spontaneously aborted, stillborn, or born with low birth weight that increases the likelihood of neonatal mortality.

The 2012 World Malaria Day Theme of Sustain Gains, Save Lives: Invest in Malaria, could not be more timely in light of the charts seen here. First we still have to make the gains in many countries, especially in respect to protecting pregnant women. We need to sustain gains, not backslide. This can only be done if donors and health ministries continue to fund MIP control activities and health program managers in both malaria control and reproductive health sincerely collaborate.

Health Systems &IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 11 Apr 2012

Assessing Bottlenecks, Mitigation Strategies and Lessons for the Liberia Malaria in Pregnancy Programming

On April 5th 2011 the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health observed Global Health Day. A key event was a series of poster presentations by students who had won global health grants to undertake field projects. Today we are sharing a second presentation about malaria in pregnancy in Liberia. The results from this Case Study in Liberia feature IPT Uptake.

Contributors: Liz Posey, MPH Candidate, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Ngozi Enwerem, MPH Candidate, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Liberia is a target country for the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) with the goal of reducing related mortality by 70%. To achieve this, the country must reach 85% coverage, with proven therapeutic interventions, of the two most vulnerable groups, children under 5 and pregnant women. Despite concerted efforts to increase the number of women who receive two or more doses of intermittent preventive treatment (IPT) with the recommended antimalarial drug during antenatal care visits (ANC); the Global Fund August 2011 grant report which uses the Health Management Information Systems (HMIS) data for 2011 documents a trend of IPT uptake for pregnant women that is consistently 28-50% below target for every reporting period. Additionally, the Liberia Malaria Indicator Survey (LMIS) 2009 reported that 54% of pregnant women did not take the two or more doses of IPT as recommended during ANC visits. A case study was conducted using a tool created by JHPIEGO and WHO to identify the gaps, challenges and strengths of the Malaria in Pregnancy Program.

Identified Gaps and Challenges Surrounding Low IPT 2 Uptake Include:

Identified Gaps and Challenges Surrounding Low IPT 2 Uptake Include:

- Issues with recording and transferring antenatal attendance and IPT recipient data, arise as a result of overworked health care workers who are simultaneously responsible for administration, reporting , antenatal care and treatment, and prevention education which leads to underreporting of IPT distribution (Photo at right shows Ngozi reviewing clinic records with staff to learn more about IPT recording).

- The number of women that receive IPT 1 is always higher in all facilities. Pregnant women face logistical challenges in returning to receive the second dose or as a result of women arriving for appointments too late in their pregnancy to receive the second dose. Accurately Tracking IPT use is a challenge because patients migrate from county to county based on the perceived quality of care received at a health care facility.

- The health facilities are not consistently communicating the need for pregnant women to return for a second dose due to understaffing and lack of communication and behavior change messaging and strategy addressing IPT 1 and 2.

Opportunities to Leverage Strengths to Address Challenges:

Opportunities to Leverage Strengths to Address Challenges:

- Unparalleled collaboration and integration in programming, monitoring and evaluation and policy development between partners, funders, and the MOH which provides a ripe opportunity to align resources and strategy to address existing challenges (Photo at right shows Ngozi and Liz at one health facility where observations were made).

- Rich history with the revitalized general community health volunteers system in Liberia. Strong structures in place that can be further strengthened through strategies to address compensation, motivation, community buy-in/perception.

- Strong track record of success using communication and behavior change messaging to increase use of long lasting insecticide treated nets, this can be similarly leveraged to improve IPT 2 uptake.

- Strong trained traditional midwives network that can be increasingly leveraged to promote early ANC visits and adherence to IPT 1 and 2 in coordination with a strong IEC/BCC campaign.

- Efforts underway to build a warehouse and strengthen the supply chain management system at all levels.

- Integrated monitoring and evaluation system utilized by all partners. Plans in place to address data accuracy. These efforts also include potential plans to pilot mobile health platforms to address issues with tracking.

These findings will guide the national malaria and reproductive health programs in serving pregnant women better and protecting them from malaria.

Communication &IPTp Bill Brieger | 10 Apr 2012

Mobile Technology to Increase ANC Attendance and IPTp Uptake in Uganda

On April 5th 2011 the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health observed Global Health Day. A key event was a series of poster presentations by students who had won global health grants to undertake field projects. Several were on malaria. We are fortunate that the presentation below has been shared with us. Hopefully more will follow.

Use of Mobile Technology to Increase ANC Attendance and IPTp Uptake – Results from a Pilot Study in Uganda

Use of Mobile Technology to Increase ANC Attendance and IPTp Uptake – Results from a Pilot Study in Uganda

Hsin-yi Lee, MSPH Candidate, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

In search of innovative ways to increase IPTp uptake, the Stop Malaria Project (SMP) in Uganda wished to investigate whether mobile technology can be part of the solution. With nearly 42% of the population owning a mobile phone, mobile technology has demonstrated its incredible potential creates an impact at scale.

The SMP SMS pilot campaign was designed to address the issue of irregular Antenatal Care (ANC) attendance and low uptake of IPTp by sending out text message reminders to pregnant women and their close contact. The program was piloted at four facilities in Mukono District with 327 pregnant enrolled during their first antenatal visit.

Results from a post-campaign survey shows that after adjusting for control variables, program exposure remained a significant factor to determining ANC and IPTp completion rates. Respondents who received three to four messages had the highest odds for completing their ANC visits and were five times more likely to complete two doses of IPTp compared to those that received less than two messages.

Results also show that women whose husband or other contact had talked to them about the messages had higher ANC completion rates. The husband felt a “shared responsibility†about the women’s antenatal care by receiving the message on his phone. An unexpected outcome of the campaign was the clients increased trust towards the facility and health providers. Respondents from the survey had talked about how the messages showed that “the providers were responsible†and “caring.â€

The Pilot SMS Campaign has demonstrated that text messages can play an effective role in promoting antenatal care attendance and uptake of IPTp. However, voice messaging methods should be further explored to overcome the issue of illiteracy. How to integrate a mobile health component into routine antenatal care in a resource limit setting is another pressing issue for program scale-up.

The Pilot SMS Campaign has demonstrated that text messages can play an effective role in promoting antenatal care attendance and uptake of IPTp. However, voice messaging methods should be further explored to overcome the issue of illiteracy. How to integrate a mobile health component into routine antenatal care in a resource limit setting is another pressing issue for program scale-up.

Further reading for similar mhealth programs:

IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy &Surveillance Bill Brieger | 18 Jun 2011

The changing face of malaria in maternal health

Jhpiego organized a panel attended by over 80 people at the just concluded Global Health Council annual conference entitled, “The changing face of malaria in maternal health,” moderated by Bill Brieger and coordinated by Aimee Dickerson. The overlap between high malaria prevalence and high maternal mortality in Africa was stressed. Although both are generally decreasing, the pace of change is quite slow for meeting Millennium Development Goals and malaria elimination targets. The time of neglecting malaria in pregnancy (MIP) should be over.

As efforts increase toward malaria elimination and the epidemiology of malaria changes, we need to be prepared at the country and global levels. This was illustrated through four presentations that focused on …

As efforts increase toward malaria elimination and the epidemiology of malaria changes, we need to be prepared at the country and global levels. This was illustrated through four presentations that focused on …

- Nigeria, a high burden country, needs to consider ways to scale up

- Rwanda, a country closing in on elimination, needs to more carefully define and target MIP transmission

- New interventions developed through research and

- Rolling out these new interventions through donor support

Enobong Ndekhedehe of Community Partners for Development based in Akwa Ibom State Nigeria spoke on community involvement to increase IPTp & ITN coverage in a highly endemic area. This joint project with Jhpiego, sponsored by the ExxonMobil Foundation, showed successfully that community volunteers supported by front-line antenatal clinic staff could greatly increase uptake of intermittent preventive treatment and thus provided a model for scale up in a high burden country.

Corine Karema who heads the National Malaria Control Program in the Rwanda Ministry of Health, addressed the feasibility of determining the prevalence of MIP during ANC in an era of declining incidence. Intense distribution of long lasting insecticide treated nets and wide availability of artemisinin-based combination therapy for malaria treatment at the community level have resulted in a 70% decline in malaria incidence between 2005 & 2010. Good ANC coverage and availability of staff to test pregnant women on their first ANC visit were found to bode well for providing not only an opportunity for pregnancy-specific prevalence determination, but also an opportunity for future interventions based on routing screening and treatment.

Theonest Mutabingwa from the Hubert Kairuki Memorial University, Tanzania talked on “The future MIP research agenda in the context of malaria elimination,” based on the plans and experiences of the Malaria in Pregnancy Consortium (MIPc), of which he is a member. MIPc teams from African and northern research institutes are looking into such issues as the changing role of prevention (e.g. IPTp vs screening and treatment), When is it optimal to change interventions (use of modelling), what are the changing patterns of disease epidemiology and immunity in pregnant women, what are the criteria or thresholds upon which to switch control strategies, what should constitute guidelines to define high/moderate, low and very low transmission settings, among others.

Theonest Mutabingwa from the Hubert Kairuki Memorial University, Tanzania talked on “The future MIP research agenda in the context of malaria elimination,” based on the plans and experiences of the Malaria in Pregnancy Consortium (MIPc), of which he is a member. MIPc teams from African and northern research institutes are looking into such issues as the changing role of prevention (e.g. IPTp vs screening and treatment), When is it optimal to change interventions (use of modelling), what are the changing patterns of disease epidemiology and immunity in pregnant women, what are the criteria or thresholds upon which to switch control strategies, what should constitute guidelines to define high/moderate, low and very low transmission settings, among others.

Finally Jon Eric Tongren of the US President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) provided a donor’s perspective on MIP programming in countries with changing malaria epidemiology. This presentation showed that even with input from multiple donors, MIP intervention targets for IPT and LLIN use are well below the RBM 2010 goal of 80% and the PMI goal of 85% despite demonstrated increases in coverage of both services. Even though effective MIP interventions exist, they need to be strengthened through well-executed assessments, collaborative implementation, and careful follow-up, monitoring, and evaluation. Echoing the research agenda expressed before, the presenter stressed the need for continued surveillance to map progress and change in prevalence and adaptation of MIP strategies as prevalence changes.

MIP control faces a double challenge. Since this component of national malaria control programs has often been neglected, there is a need to catch up and achieve 2010 coverage targets. Then moving forward, strengthened monitoring and surveillance is needed to fine tune, revise and better target MIP interventions to make a bigger impact on reducing maternal mortality in endemic countries.

Advocacy &IPTp Bill Brieger | 10 Apr 2010

Malaria Matters was named a top 50 public health blog

From: Emily Johnston

Sent: Saturday, April 10, 2010 12:04 AM

To: Brieger, William

Subject: Malaria Matters was named a top 50 public health blog

Hello Dr. Brieger

I’m just writing this to let you know about a new featured post we just made over here at Health Sherpa entitled, “Top 50 Public Health Blogs.†I thought that both you and your readers at Malaria Matters might find it to be an interesting article.

Please do let me know if you have any feedback — http://mastersofpublichealth.org/top-50-public-health-blogs.html

Malaria Matters: Bill Brieger is currently a Professor in the Health Systems Program of the Department of International Health at Johns Hopkins University as well as the Senior Malaria Adviser for JHPIEGO.

Warm Regards,

Emily Johnston

Health Sherpa

IPTp Bill Brieger | 27 Mar 2010

IPTp – are controversies preventing prevention?

According to WHO, “Malaria in pregnancy increases the risk of maternal anaemia, stillbirth, spontaneous abortion, low birth weight and neonatal death.†We have interventions to help, but are we giving them our full support?Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria among pregnant women (IPTp) using the drug Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) has been in use in antenatal clinics in Africa for over a decade. Even so, controversies remain that may deprive pregnant women of malaria protection at a time when they are most vulnerable. These controversies include questions of parasite resistance to SP and appropriate venues for administration of IPTp.

Currently WHO recommends a minimum of two doses of IPTp during pregnancy, but because of questions raised about parasite resistance to SP, WHO convened a Technical Expert Group* that concluded …

- Even though the IPTp policy was recommended and adopted in 1998 based on limited data, subsequent evidence has confirmed that IPTp is a useful intervention

- Given the possible detrimental effect that increasing SP resistance would have on the benefits and cost-effectiveness of SP-IPTp, there is uncertainty as to how long this intervention with SP will remain useful.

- Currently available SP efficacy data are insufficient to make specific and meaningful changes to current WHO recommendations on SP-IPTp. SP efficacy as currently measured in children cannot be extrapolated directly to the efficacy of IPTp. Therefore, in the absence of new data, the recommendation be streamlined to state that all countries in stable malaria transmission situations should deploy and scale up the strategy of SP-IPTp, until relevant data on its effectiveness under current conditions becomes available for WHO to review this recommendation.

Rwanda has already stopped using IPTp because of fears of SP resistance, although its neighbors have not made this move. The challenge of not providing IPTp is ensuring that two additional key interventions are in place, 1) provision of insecticide treated nets in the first trimester and 2) availability of prompt parasitological diagnosis and artemisinin-based combination therapy in antenatal clinics.

Unfortunately, countries are not achieving adequate coverage of these additional interventions to help pregnant women. It does not make sense to throw out an intervention like IPTp when we are so far from achieving RBM targets for protecting pregnant women. At present the effect of SP resistance may be more of reducing the duration of protection – not a reason to completely abandon IPTp until we have an alternative.

In the meantime people are raising questions about most of delivering IPTp. Recently Ndyomugyenyia and Katamanywa reported from Uganda that ANC attendance does not guarantee that pregnant will get a full course of IPTp. Problems of staff training and procurement and supply distribution may be in play. Also there are concerns that although most women in Africa attend ANC sometime, they may not do so early enough and at the right intervals to successful complete two IPTp doses.

These ANC attendance concerns have given rise to community approaches. A basic community mobilization approach had positive effects in attendance and coverage in Burkina Faso. A Ugandan intervention showed that provision of SP by volunteer community agents could increase IPTp coverage. While community volunteers did help increase coverage in Malawi, researchers there found that ANC attendance decreased in communities where volunteers were used. An ongoing study in Nigeria is testing community IPTp delivery that is strongly linked into ANC service provision (see abstract #632 at link).

Even if we can harness and improve the resources at antenatal clinics to achieve malaria prevention targets, we have problems in the wider environment. In most countries, contrary to official pronouncements, SP is still being sold to treat malaria in private pharmacies and shops. This inappropriate usage of SP will in fact contribute to increasing parasite resistance and decreasing efficacy of IPTp. Until countries can get proper control on their drug supplies, IPTp and even appropriate treatment generally, will be threatened.

The lack of concern about protecting SP leads one to wonder whether endemic countries and donors are really concerned about protecting pregnant women from malaria and are just using SP controversies to continue their neglect of this vulnerable group.

__________

*Technical Expert Group meeting on intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) WHO HEADQUARTERS, GENEVA, 11–13 JULY 2007.