IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 20 Aug 2013 12:46 am

Burundi- Reduce Neonatal-Mortality by Preventing Maternal Malaria

This guest blog has been re-posted from The blog by Chioma Anigbogu who is in our course, Social and Behavioral Foundations of Primary Health Care.

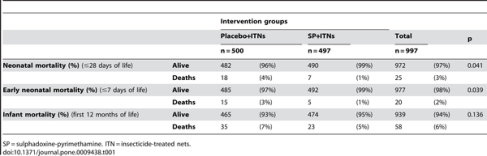

Malaria continues to severely burden many Sub-Saharan countries, including the nation of Burundi. In Burundi, 78% of the country lives in high or low transmission areas. Â In this population, pregnant women are at greater risk of experiencing spontaneous abortions, low birth weight, neonatal deaths and even anemia due to malaria. Â However, researchers have found that prevention treatment (Intermittent prevention therapy or IPT) during pregnancy can significantly reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity.

The WHO has a three-pronged recommendation for the prevention of malaria, including IPT, distribution of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) and proper management of disease. Burundi adopted an ITN policy in 2004 and has many in-country and international programs that distribute ITNs. Burundi even reports 100% treatment coverage for tested malaria cases. However, unlike some other African countries, Burundi has not adopted an IPT policy for malaria, leaving pregnant women and children extremely vulnerable.

In 2011, the government of Burundi (GOB) developed the Global Health Initiative, in partnership with international organizations, that is aimed at reducing maternal, neonatal and child health disease. The GHI holds a specific tenet regarding the “prevention and treatment of malariaâ€. In 2009 Burundi also received funds from the US- Agency for International Development (USAID) to complement already existing malaria activities. These activities sometimes include IPT but there is no formal requirement or enforcement of the treatment. WHO suggests that confusion amongst health workers may contribute to the lack of recommendation for this preventative treatment. A national policy that is developed and properly implemented would train health officials and workers in assuring that this treatment is integrated to the provision of services for women.

It would increase the overall health of the country and further bolster the work of other organizations such as Doctors without Borders and the Canadian Red Cross who are invested in Burundi’s malaria management. Adoption of this policy in Burundi will also reduce the negative impact of malaria, and may even reduce overall health spending by helping to maintaining better health for mothers and neonates.

In order to contribute your voice, leave a comment for the USAID (who works directly with Burundi), encouraging them to work with the Burundi government to adopt an IPT policy.

Photo Credit: Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders)

IPT Table:Â http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0009438