Asymptomatic &Burden &Dengue &Diagnosis &Ebola &Elimination &Epidemiology &Health Systems &ITNs &MDA &Mosquitoes &NTDs &Schistosomiasis &Schools &Vector Control &Zoonoses Bill Brieger | 30 Jun 2019

The Weekly Tropical Health News 2019-06-29

Below we highlight some of the news we have shared on our Facebook Tropical Health Group page during the past week.

Polio Persists

If all it took to eradicate a disease was a well proven drug, vaccine or technology, we would not be still reporting on polio, measles and guinea worm, to name a few. In the past week Afghanistan reported 2 wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) cases, and Pakistan had 3 WPV1 cases. Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) was reported in Nigeria (1), DRC (4) and Ethiopia (3) from healthy community contacts.

Continued Ebola Challenges

In the seven days from Saturday to Friday (June 28) there were 71 newly confirmed Ebola Cases and 56 deaths reported by the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Ministry of Health. As Ebola cases continue to pile up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with 12 more confirmed Thursday and 7 more Friday, a USAID official said four major donors have jump-started a new strategic plan for coordinating response efforts. To underscore the heavy toll the outbreak has caused, among its 2,284 cases, as noted on the World Health Organization Ebola dashboard today, are 125 infected healthcare workers, including 2 new ones, DRC officials said.

Pacific Standard explained the differences in Ebola outbreaks between DRC today and the West Africa outbreak of 2014-16. On the positive side are new drugs used in organized trials for the current outbreak. The most important factor is safe, effective vaccine that has been tested in 2014-16, but is now a standard intervention in the DRC. While both Liberia and Sierra Leone had health systems and political weaknesses as post-conflict countries, DRC’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces are currently a war zone, effectively so for the past generation. Ebola treatment centers and response teams are being attacked. There are even cultural complications, a refusal to believe that Ebola exists. So even with widespread availability of improved technologies, teams may not be able to reach those in need.

To further complicate matters in the DRC, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) “highlighted ‘unprecedented’ multiple crises in the outbreak region in northeastern DRC. Ebola is coursing through a region that is also seeing the forced migration of thousands of people fleeing regional violence and is dealing with another epidemic. Moussa Ousman, MSF head of mission in the DRC, said, ‘This time we are seeing not only mass displacement due to violence but also a rapidly spreading measles outbreak and an Ebola epidemic that shows no signs of slowing down, all at the same time.’”

NIPAH and Bats

Like Ebola, NIPAH is zoonotic, and also involves bats, but the viruses differ. CDC explains that, “Nipah virus (NiV) is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae, genus Henipavirus. NiV was initially isolated and identified in 1999 during an outbreak of encephalitis and respiratory illness among pig farmers and people with close contact with pigs in Malaysia and Singapore. Its name originated from Sungai Nipah, a village in the Malaysian Peninsula where pig farmers became ill with encephalitis.

A recent human outbreak in southern India has been followed up with a study of local bats. In a report shared by ProMED, out of 36 Pteropus species bats tested for Nipah, 12 (33%) were found to be positive for anti-Nipah bat IgG antibodies. Unlike Ebola there are currently no experimental drugs or vaccines.

Climate Change and Dengue

Climate change is expected to heighten the threat of many neglected tropical diseases, especially arboviral infections. For example, the New York Times reports that increases in the geographical spread of dengue fever. Annually “there are 100 million cases of dengue infections severe enough to cause symptoms, which may include fever, debilitating joint pain and internal bleeding,” and an estimated 10,000 deaths. Dengue is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes that also spread Zika and chikungunya. A study, published Monday in the journal Nature Microbiology, found that in a warming world there is a strong likelihood for significant expansion of dengue in the southeastern United States, coastal areas of China and Japan, as well as to inland regions of Australia. “Globally, the study estimated that more than two billion additional people could be at risk for dengue in 2080 compared with 2015 under a warming scenario.”

Schistosomiasis – MDA Is Not Enough, and Neither Are Supplementary Interventions

Schistosomiasis is one of the five neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) that are being controlled and potentially eliminated through mass drug administration (MDA) of preventive chemotherapy (PCT), in this case praziquantel. In The Lancet Knopp et al. reported that biannual MDA substantially reduced Schistosomiasis haematobium prevalence and infection intensity but was insufficient to interrupt transmission in Zanzibar. In addition, neither supplementary snail control or behaviour change activities did not significantly boost the effect of MDA. Most MDA programs focus on school aged children, and so other groups in the community who have regular water contact would not be reached. Water and sanitation activities also have limitations. This raises the question about whether control is acceptable for public health, or if there needs to be a broader intervention to reach elimination?

Trachoma on the Way to Elimination

Speaking of elimination, WHO has announced major “sustained progress” on trachoma efforts. “The number of people at risk of trachoma – the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness – has fallen from 1.5 billion in 2002 to just over 142 million in 2019, a reduction of 91%.” Trachoma is another NTD that uses the MDA strategy.

The news about NTDs from Dengue to Schistosomiasis to Trachoma is complicated and demonstrates that putting diseases together in a category does not result in an easy choice of strategies. Do we control or eliminate or simply manage illness? Can our health systems handle the needs for disease elimination? Is the public ready to get on board?

Malaria Updates

And concerning being complicated, malaria this week again shows many facets of challenges ranging from how to recognize and deal with asymptomatic infection to preventing reintroduction of the disease once elimination has been achieved. Several reports this week showed the particular needs for malaria intervention ranging from high burden areas to low transmission verging on elimination to preventing re-introduction in areas declared free from the disease.

In South West, Nigeria Dokunmu et al. studied 535 individuals aged from 6 months were screened during the epidemiological survey evaluating asymptomatic transmission. Parasite prevalence was determined by histidine-rich protein II rapid detection kit (RDT) in healthy individuals. They found that, “malaria parasites were detected by RDT in 204 (38.1%) individuals. Asymptomatic infection was detected in 117 (57.3%) and symptomatic malaria confirmed in 87 individuals (42.6%).

Overall, detectable malaria by RDT was significantly higher in individuals with symptoms (87 of 197/44.2%), than asymptomatic persons (117 of 338/34.6%)., p = 0.02. In a sub-set of 75 isolates, 18(24%) and 14 (18.6%) individuals had Pfmdr1 86Y and 1246Y mutations. Presence of mutations on Pfmdr1 did not differ by group. It would be useful for future study to look at the effect of interventions such as bednet coverage. While Southwest Nigeria is a high burden area, the problem of asymptomatic malaria will become an even bigger challenge as prevalence reduces and elimination is in sight.

Sri Lanka provides a completely different challenge from high burden areas. There has been no local transmission of malaria in Sri Lanka for 6 years following elimination of the disease in 2012. Karunasena et al. report the first case of introduced vivax malaria in the country by diagnosing malaria based on microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests. “The imported vivax malaria case was detected in a foreign migrant followed by a Plasmodium vivax infection in a Sri Lankan national who visited the residence of the former. The link between the two cases was established by tracing the occurrence of events and by demonstrating genetic identity between the parasite isolates. Effective surveillance was conducted, and a prompt response was mounted by the Anti Malaria Campaign. No further transmission occurred as a result.”

Bangladesh has few but focused areas of malaria transmission and hopes to achieve elimination of local transmission by 2030. A particular group for targeting interventions is the population of slash and burn cultivators in the Rangamati District. Respondents in this area had general knowledge about malaria transmission and modes of prevention and treatment was good according to Saha and the other authors. “However, there were some gaps regarding knowledge about specific aspects of malaria transmission and in particular about the increased risk associated with their occupation. Despite a much-reduced incidence of malaria in the study area, the respondents perceived the disease as life-threatening and knew that it needs rapid attention from a health worker. Moreover, the specific services offered by the local community health workers for malaria diagnosis and treatment were highly appreciated. Finally, the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITN) was considered as important and this intervention was uniformly stated as the main malaria prevention method.”

Kenya offers some lessons about low transmission areas but also areas where transmission may increase due to climate change. A matched case–control study undertaken in the Western Kenya highlands. Essendi et al. recruited clinical malaria cases from health facilities and matched to asymptomatic individuals from the community who served as controls in order to identify epidemiological risk factors for clinical malaria infection in the highlands of Western Kenya.

“A greater percentage of people in the control group without malaria (64.6%) used insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) compared to the families of malaria cases (48.3%). Low income was the most important factor associated with higher malaria infections (adj. OR 4.70). Houses with open eaves was an important malaria risk factor (adj OR 1.72).” Other socio-demographic factors were examined. The authors stress the need to use local malaria epidemiology to more effectively targeted use of malaria control measures.

The key lesson arising from the forgoing studies and news is that disease control needs strong global partnerships but also local community investment and adaptation of strategies to community characteristics and culture.

Mosquitoes &Uncategorized &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 19 May 2019

Malaria – an old disease attacking the young population of Kenya

Wambui Waruingi recently described her experiences working on malaria in Kenya on the site, “Social, Cultural & Behavioral Issues in PHC & Global Health.” Her thoughts and lessons are found below.

Malaria is an old disease, and not unfamiliar to the people of Lwala, Migori county, Nyanza province, situated in Kenya, East Africa. The most vulnerable are pregnant women and young children.The Lwala Community Alliance have reduced the rate of under 5 mortality to 20% of what it was 10 years ago, and about 30% of what it is in Migori county (reported 29 deaths/ 1000 in 2018) https://lwala.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Lwala-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

Of the scourges that remain, malaria is one of them.

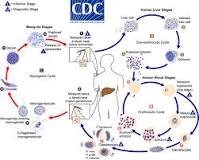

Malaria is caused by a protozoal species called Plasmodium spp; the most severe is Plasmodium falciparum, the predominant type in the region.It’s life cycle exemplifies evolution at it’s most sophisticated, albeit vulnerable, needing two hosts of different species to complete it’s life cycle, the mosquito, and mammalian species in stages of asexual then asexual reproduction respectively. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/malaria/symptoms-causes/syc-20351184https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html

The mosquito types responsible for malaria in the area are A. gambiae spp and A. arabiensis spp. To complete it’s life cycle, the mosquito requires water, or an aquatic environment to develop it’s larvae. This insect therefore seeks to lay it’s eggs in pools of fresh water, abundant in the area due to Lake Victoria, and important source of the local staple fish, and areas of underdeveloped grassland surrounding the lake and village. https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-9-62

WHO reported 219 million cases of malaria world wide, with 435,000 deaths in the same year. In this day and age, malaria remains burdensome in 11 countries, 10 of them being in Africa. WHO recommends a focused response. https:// who.int/malaria/en/. I advocate a focus on prevention by eradicating mosquitoes and episodes of mosquito bites in the region. WHO vector control guidelines run along the idea of chemical and biological larvicides, topical repellents,and personal protective measures, such as bed nets, wearing long sleeves and pants (hard to do in the heat of Migori), bug spray and insecticide treated nets. These are effective.

In the area, mosquitoes capitalize on both daytime and nighttime feeding. Lwala benefits from a mosquito net distribution program so there is at least 1 net/ per household and a coverage of about 95%, https://lwala.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Lwala-2018-Annual-Report.pdf, but there is an average of 5.5 individuals per household,

file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Migori%20County.pdf , so it conceivable that not all children under 5 currently sleep under a net.

Let’s start by making sure they do by scaling up this program, so that the number of nets corresponds with the number of individuals per household.

Lwala is an active community, and while use of nets will eliminate night feeders such as A. gambiae , little children will be susceptible to mosquito bites given that they are outdoors nearly daily helping with activities such as fishing, goat herding, fetching water and so forth. That is why active programs for mosquito eradication make so much sense in the region. While promoting personal prevention measures such as the use of “bugspray” containing effective substances such as DEET, efforts by the Bill and Melissa gates foundation, through the Malaria R&D (research and development) active since 2004, have devoted over $323 million dollars, about 20% ($50.4 million) of which has gone to the Innovative Vector Control Consortium, (IVCC) led by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The aim is to fast track improved insecticides, both biological and chemical, and other measures of vector control. I suggest that partnership with the IVCC be scaled up in the area, allowing Lwala to be first line in any benefits thereof. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2010/11/IVCC-Develops-New-Public-Health-Insecticides, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2005/10/Gates-Foundation-Commits-2583-Million-for-Malaria-Research

Finally, it’s official. Research endorses use of nets and indoor residual spraying as an effective way to reduce malaria density. https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-016-1214-9. This should be coupled with house improvement, since much of traditional and poverty-maintained materials, allow environments in which the mosquito can hide, to come out later to feed, and even breed. In Migori county, 72% of the homes have earth floors, 76% have corrugated roofs, and 21% have grass-thatched roofs. file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Migori%20County.pdf

All these promote a healthy habitat for the mosquito during the rainy season, and easy entry and hiding places all year round. Funding to improve house types so that locally-sourced but sturdy, water-proof homes can be built, will eliminate opportunities for the mosquito to access and bite young children.

Let’s get stakeholders vested in this effective, yet economical way to address malaria deaths in the youngest children. Starting now, funding should be diverted from costly treatments with ever mounting resistance patterns, to causing extinction of the Anopheles mosquito in Migori county. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”http://drjarodhalldpt.blogspot.com/2018/02/an-ounce-of-prevention-is-worth-pound.html

ITNs &Universal Coverage &Vector Control &Zero Malaria Bill Brieger | 25 Apr 2019

Zero Malaria Starts with Universal Coverage: Part 1 Nets

WHO says, “Malaria elimination and universal health coverage go hand in hand,” at a special event during the 72st World Health Assembly. To achieve zero malaria, the goal of involving everyone from the policy maker to the community member must have a focus on achieving universal health coverage (UHC) of all malaria interventions ranging from insecticide treated bednets (ITNs) to appropriate provision of malaria diagnostics and medicines. Many of the studies to date have focused on ITNs, which include long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs), but nationwide monitoring through the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), the Malaria Indicator Surveys (MIS) and the Multi-Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS).

UNICEF’s website provides a data repository that includes the most recent DHS, MIS and MICS survey data per country between 2014 and 2017. For the indicator of one ITN per to people in a household, shows Angola at only 13%, most countries for which recent data are available reached between 40-50%. Only two achieved above 60% on a point-in-time survey, Uganda at 62% and Sao Tome and Principe at 95%. The website shows information that where there were multiple surveys in a country during the period, there were variations, sometimes quite wide, over the years. Aside from the fact that the surveys may have had slightly different procedures, the problem remains of achieving and sustaining UHC for ITNs.

MICS survey data per country between 2014 and 2017. For the indicator of one ITN per to people in a household, shows Angola at only 13%, most countries for which recent data are available reached between 40-50%. Only two achieved above 60% on a point-in-time survey, Uganda at 62% and Sao Tome and Principe at 95%. The website shows information that where there were multiple surveys in a country during the period, there were variations, sometimes quite wide, over the years. Aside from the fact that the surveys may have had slightly different procedures, the problem remains of achieving and sustaining UHC for ITNs.

Another factor that affects maintaining UHC for ITNs, assuming the target can be met is the durability of nets. The physical integrity as well as the insecticide efficacy can decline over time. Intact nets may lose their insecticide through improper washing and drying, yet still prevent mosquito bites to the individual sleeping under them. Nets with holes may still maintain a minimal level of effective insecticide and may not fully prevent bites but ultimately kill the mosquito that flies through. Researchers in Senegal have been grappling with these challenges.

Program managers must themselves grapple with whether such compromised nets count toward universal coverage as well as how often to conduct net replacement campaigns. A report from community surveys in Uganda during 2017 found that, “Long-lasting insecticidal net ownership and coverage have reduced markedly in Uganda since the last net distribution campaign in 2013/14.” UHC for ITNs is always a moving target.

Program managers must themselves grapple with whether such compromised nets count toward universal coverage as well as how often to conduct net replacement campaigns. A report from community surveys in Uganda during 2017 found that, “Long-lasting insecticidal net ownership and coverage have reduced markedly in Uganda since the last net distribution campaign in 2013/14.” UHC for ITNs is always a moving target.

A frequently unaddressed issue in seeking to improve ITN coverage is whether it makes a difference in malaria disease. A study in Malawi reported that although ITNs per household increased from 1.1 in 2012 to 1.4 in 2014, the prevalence of malaria in children increased over the period from 28% to 32%. The authors surmised that factors such as insecticide resistance, irregular ITN use and inadequate coordinated use of other malaria control interventions may have influenced the results. This shows that UHC for ITNs cannot be viewed in isolation.

This brings up the issue of the role of the many different vector control measures available. Researchers in Côte d’ Ivoire examined the use of eave nets and window screening. At present eave nets are mainly deployed in research contexts but use of window and door screening and netting are a commercially available interventions that households employ on their own. One wonders then whether UHC should focus on how the household and the people therein are protected by any malaria vector intervention.

Here the discussion should focus on the question raised by colleagues in the USAID/PMI Vectorworks Project. WHO declared a goal of universal ITN coverage in 2009 using the target f one ITN/LLIN for every two household members. Vectorworks found that a decade on only one instance of a country briefly achieving 80% of this UHC net target, whereas no others reached above 60%. In fact, the bigger the household, the less chance there was of meeting the two people for one ITN target. Just because people live in a household that has the requisite number of nets, does not guarantee the actual target for sleeping under a net can be achieved because of practical or cultural realities in a household. Neither the minimal indicator of having at least one net in a household, or the ideal or ‘perfect’ indicator of UHC are satisfactory for judging population protection.

Here the discussion should focus on the question raised by colleagues in the USAID/PMI Vectorworks Project. WHO declared a goal of universal ITN coverage in 2009 using the target f one ITN/LLIN for every two household members. Vectorworks found that a decade on only one instance of a country briefly achieving 80% of this UHC net target, whereas no others reached above 60%. In fact, the bigger the household, the less chance there was of meeting the two people for one ITN target. Just because people live in a household that has the requisite number of nets, does not guarantee the actual target for sleeping under a net can be achieved because of practical or cultural realities in a household. Neither the minimal indicator of having at least one net in a household, or the ideal or ‘perfect’ indicator of UHC are satisfactory for judging population protection.

The Vectorworks team suggests that, “Population ITN access indicator is a far better indicator of ‘universal coverage’ because it is based on individual people,” and can be compared to, “The proportion of the population that used an ITN the previous night, which enables detailed analysis of specific behavioral gaps nationally as well as among population subgroups.” Population access to ITNs therefore, provides a batter basis for more realistic policies and strategies.

We have seen that defining as well as achieving universal coverage of malaria interventions is a challenging prospect. For example, do we base our monitoring on households or populations? Do we have the funds and technical capacity to implement and sustain the level of coverage required to have an impact on malaria transmission and move toward elimination? Are we able to introduce new, complimentary and appropriate interventions as a country moves closer to elimination?

A useful perspective would be determination if households and individuals even benefit from any part of the malaria package, even if everyone does not have access and utilize all components. This may be why zero malaria has to start with each person living in endemic areas.

Borders &CHW &Climate &Elimination &IPTi &Sahel &Surveillance &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 26 Sep 2018

Hopefully Malaria Elimination will not be the SaME

The Sahel Malaria Elimination Initiative (SaME) has been launched, but builds on a long history of cooperation in the region. Efforts by eight Sahelian countries to share lessons and strategies mirrors the Elimination Eight group on the opposite end of the continent.

The Roll Back Malaria (RBM) Partnership to End Malaria announced that in Dakar on 31st August 2018, the health “ministers from Burkina Faso, Cabo Verde, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal and The Gambia established a new regional platform to combine efforts on scaling up and sustaining universal coverage of anti-malarials and mobilizing financing for elimination.” The group plans a fast-track introduction of “innovative technologies to combat malaria and develop a sub-regional scorecard that will track progress towards the goal of eliminating malaria by 2030.” This will build on the existing country scorecard that has been developed and implemented by AMLA2030 for all countries in the region and tracks roll out of key malaria and health interventions. The Sahel Malaria Elimination Initiative will be hosted by the West African Health Organization, a specialised agency of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

RBM explains that while the eight countries will work together, they do not have a homogenous epidemiological picture or experience with malaria programming. The Sahel experiences 20 million annual malaria cases, according to RBM, and “the Sahel region has seen both achievements and setbacks in the fight against the disease in recent years.” These eight have a highly variable malaria experience. Burkina Faso and Niger continue to be among the countries with high malaria burdens. Cabo Verde is on target for malaria free status by 2020. The Gambia, Mauritania and Senegal are reorienting their national malaria program towards malaria elimination. A benefit of this epidemiological and programmatic diversity is that countries can learn important lessons from each other.

The SaME Initiative will use the following main approaches to accelerate the combined efforts towards the attainment of malaria elimination in the sub-region:3

- Regional coordination

- Advocacy to keep malaria elimination high on the development and political agenda

- Sustainable financing mechanisms

- Cross-border collaboration and ensuring accountability

- Fast-track the introduction of innovative and progressive technologies

- Re-enforcing the Regional regulatory mechanism for quality of malaria commodities and introduction of new tools.

- Establish malaria observatory, regional surveillance, and best practice sharing

Collaboration across borders on vector control is an example of needed regional coordination. According to Thomson et al., climate variations have the potential to significantly impact vector-borne disease dynamics at multiple space and time scales. Another challenge to vector control in the region is the issue of how mosquitoes repopulate areas after an extended dry season. Huestis et al. examined the response of Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles gambiae to environmental cues in season change in the Sahel.

In addition to a history of cooperation, Sahelian countries share a unique malaria intervention, Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) that as the name implies, built on the reality of highly seasonal transmission in the region. SMC grew out of over five years of research in several African settings to test the effect of what was originally termed Intermittent Preventive Treatment for Infants (and later children) or IPTi.

Like IPT for pregnant women, SMC would be given monthly for at least 3-4 months, but unlike IPTp, SMC would consist of a combination two medicines, amodiaquine plus sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (AQ+SP), which required a three daily doses (SP alone as used in IPTp consists on one dose). SMC could not therefore, be delivered effectively as a clinic-based intervention, but “should be integrated into existing programmes, such as Community Case Management and other Community Health Workers schemes.” Access to SMC by pre-school aged children as delivered by CHWs was found to be more equitable than sleeping under an LLIN. SMC has been recommended for school-age children, a neglected group that bears a substantial burden of malaria.

Closely linked to surveillance is modeling the spatial and temporal variability of climate parameters, which is crucial to tackling malaria in the Sahel. This requires reliable observations of malaria outbreaks over a long time period. To date efforts are mainly linked to climate variables such as rainfall and temperature as well as specific landscape characteristics. Other environmental and socio-economic factors that are not included in this mechanistic malaria model.

The Sahel Malaria Elimination initiative offers a unique collaborative opportunity for countries to improve on the quality of proven interventions like SMC and test and take to scale new strategies like school-based malaria programs. Regional coordination can produce better, timelier and longer-term surveillance and better understanding of and actions against malaria vectors. Readers will surely be anticipating the publishing of the regular progress malaria elimination scorecards as promised by SaME leadership.

ITNs &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 26 Jun 2018

Tanzania Malaria Indicator Survey, ITNs and the View of the Press

Take away messages by the Press sometimes need a bit of clarification. A recent report in The Citizen (Dar es Salaam) expressed that the author was ‘startled’ to mean from the recent Malaria Indicator Suvey (MIS/DHS 2017) that there is high malaria prevalence in regions that also have high insecticide treated bednet ownership and use, implying that nets might not be effective. Actually the preliminary Key Indicators Report showed the overlap between prevalence and nets but did not actually present statistical analysis comparing the two to show whether actual sleeping under the net is associated with prevalence one way or the other.

Take away messages by the Press sometimes need a bit of clarification. A recent report in The Citizen (Dar es Salaam) expressed that the author was ‘startled’ to mean from the recent Malaria Indicator Suvey (MIS/DHS 2017) that there is high malaria prevalence in regions that also have high insecticide treated bednet ownership and use, implying that nets might not be effective. Actually the preliminary Key Indicators Report showed the overlap between prevalence and nets but did not actually present statistical analysis comparing the two to show whether actual sleeping under the net is associated with prevalence one way or the other.

The reporter quoted Dr William Kisinza, director and chief researcher at the Amani Research Centre of the National Institute for Medical Research as saying “This shows that mosquito bed-nets aren’t the only solution in addressing malaria in Tanzania,” and while this is true, it should not be construed as meaning nets don’t work. Any national malaria strategy uses ITNs in combination with other interventions to have a comprehensive program, including indoor residual spraying, which is also mentioned in the new article.

The reporter quoted Dr William Kisinza, director and chief researcher at the Amani Research Centre of the National Institute for Medical Research as saying “This shows that mosquito bed-nets aren’t the only solution in addressing malaria in Tanzania,” and while this is true, it should not be construed as meaning nets don’t work. Any national malaria strategy uses ITNs in combination with other interventions to have a comprehensive program, including indoor residual spraying, which is also mentioned in the new article.

Dr Kisinza was also quoted as saying, “In Kigoma and Mtwara, bed-nets are used in fishing. There’s a need for behavioural change, if the problem is to be effectively addressed.” This is a real problem but anecdotal. In order to make a clearer point it would be necessary to test the connection between net ownership and use and do a follow-up study to see if in fact those owning but not sleeping under the nets are practicing alternative net usage.

Actually key findings from the preliminary MIS report include the fact that while 78% of households have one ITN, only 45% have at least one for every two people. Hence it is not surprising that only 55% of children under the age of 5 and 62% of pregnant women reported sleeping under a net. These are important service gaps that must be addressed. Certainly all countries need to monitor the effectiveness of nets and insecticide resistance.

Actually key findings from the preliminary MIS report include the fact that while 78% of households have one ITN, only 45% have at least one for every two people. Hence it is not surprising that only 55% of children under the age of 5 and 62% of pregnant women reported sleeping under a net. These are important service gaps that must be addressed. Certainly all countries need to monitor the effectiveness of nets and insecticide resistance.

Analysis of net use and malaria parasitaemia among the children can and should be presented to address the reporter’s questions as well as provide a clue to potential insecticide resistance.

Economics &ITNs &Mosquitoes &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 25 Oct 2017

Mis-Use of Insecticide Treated Nets May Actually Be Rational

People have sometimes question whether insecticide treated nets (ITNs) provided for free are valued by the recipients. Although this is not usually a specific question in surveys, researchers found in a review of 14 national household surveys that free nets received through a campaign were six times more likely to be given away than nets obtained through other avenues such as routine health care or purchased from shops.

Giving nets away to other potential users, not hanging nets or not sleeping under nets at least imply that the nets could potentially be used for their intended purpose. What concerns many is that nets may be used for unintended and inappropriate reasons. Often the evidence is anecdotal, but photos from Nigeria and Burkina Faso shown here document cases where nets were found to cover kiosks, make football goalposts, protect vegetable seedlings and fence in livestock.

Giving nets away to other potential users, not hanging nets or not sleeping under nets at least imply that the nets could potentially be used for their intended purpose. What concerns many is that nets may be used for unintended and inappropriate reasons. Often the evidence is anecdotal, but photos from Nigeria and Burkina Faso shown here document cases where nets were found to cover kiosks, make football goalposts, protect vegetable seedlings and fence in livestock.

Newspapers tend to quote horrified health or academic staff when reporting this, such as this statement from Mozambique, “The nets go straight out of the bag into the sea.” The Times said that net misuse squandered money and lives when they observed that “Malaria nets distributed by the Global Fund have ended up being used for fishing, protecting livestock and to make wedding dresses.”

Two years ago the New York Times reported that, “Across Africa, from the mud flats of Nigeria to the coral reefs off Mozambique, mosquito-net fishing is a growing problem, an unintended consequence of one of the biggest and most celebrated public health campaigns in recent years.”5 Not only were people not being protected from malaria, but the pesticide in these ‘fishing nets’ was causing environmental damage. The article explains that the problem of such misuse may be small, but that survey respondents are very unlikely to admit to alternative uses to interviewers.

Two years ago the New York Times reported that, “Across Africa, from the mud flats of Nigeria to the coral reefs off Mozambique, mosquito-net fishing is a growing problem, an unintended consequence of one of the biggest and most celebrated public health campaigns in recent years.”5 Not only were people not being protected from malaria, but the pesticide in these ‘fishing nets’ was causing environmental damage. The article explains that the problem of such misuse may be small, but that survey respondents are very unlikely to admit to alternative uses to interviewers.

Similarly El Pais website featured an article on malaria in Angola this year with a striking lead photo of children fishing in the marshes near their village in Cubal with a LLIN. A video from the New York Times frames this problem in a stark choice: sleep under the nets to prevent malaria or them it to catch fish and prevent starvation.[v]

More recently, researchers who examined net use data from Kenya and Vanuatu found that alternative LLIN use is likely to emerge in impoverished populations where these practices had economic benefits like alternative ITN uses sewing bednets together to create larger fishing nets, drying fish on nets spread along the beach, seedling crop protection, and granary protection. The authors raise the question whether such uses are in fact rational from the perspective of poor people.

More recently, researchers who examined net use data from Kenya and Vanuatu found that alternative LLIN use is likely to emerge in impoverished populations where these practices had economic benefits like alternative ITN uses sewing bednets together to create larger fishing nets, drying fish on nets spread along the beach, seedling crop protection, and granary protection. The authors raise the question whether such uses are in fact rational from the perspective of poor people.

An important fact is that not all ovserved ‘mis-use’ of nets is really inappropriate use. A qualitative study in the Kilifi area of coastal Kenya demonstrated local ‘recycling’ of old ineffective nets. The researchers clearly found that in rural, peri-urban and urban settings people adopted innovative and beneficial ways of re-using old, expired nets, and those that were damaged beyond repair. Fencing for livestock, seedlings and crops were the most common uses in this predominantly agricultural area. Other domestic uses were well/water container covers, window screens, and braiding into rope that could be used for making chairs, beds and clotheslines. Recreational uses such as making footballs, football goals and children’s swings were reported

What we have learned here is that we should not jump to conclusions when we observe a LLIN that is set up for another purpose than protecting people from mosquito bites. Alternative uses of newly acquired nets do occur and may seem economically rational to poor communities. At the same time we must ensure that mass campaigns pay more attention to community involvement, culturally appropriate health education and onsite follow-up, especially the involvement of community health workers. Until such time as feasible safe disposal of ‘retired’ nets can be established, it would be good to work with communities to help them repurpose those nets that no longer can protect people from malaria.

Elimination &Surveillance &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 11 Apr 2017

A malaria elimination framework that includes high prevalence countries, too

When the Nigeria Malaria Control Program changes its name to Nigeria Malaria Elimination Program (NMEP) a few years ago, people wondered whether this was getting too far ahead of the situation in one of the highest burden malaria countries in the world. The recently released Framework for Malaria Elimination by the Global Malaria Program of WHO shows that all endemic countries can fit into the elimination process.

Recent Webinar by WHO’s Global Malaria Program stressed that all countries have a role in malaria elimination

The Framework stresses that, “Every country can accelerate progress towards elimination through evidence-based strategies, regardless of the current intensity of transmission and the malaria burden they may carry.” The Three pillars of the malaria elimination framework have room for high burden countries. Pillar 1 states that, “Ensure universal access to malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment.”

First it is important to understand that the Framework defines malaria elimination as the cessation of indigenous mosquito-borne transmission of malaria throughout a country. The Framework also observes that even within countries there are diverse transmission areas. Some are not amenable to malaria transmission, while others may be amenable but do not experience transmission.

It is important to realize that malaria transmission in most countries is characterized by diversity and complexity. Areas where transmission is occurring range from very low transmission zones where hotspots erupt to high levels of ongoing transmission. Thus even high burden countries may have variation that require development of intervention packages tailored to the specific transmission setting.

This stratifi cation and development of appropriate intervention packages requires, “Excellent surveillance and response are the keys to achieving and maintaining malaria elimination; information systems must become increasingly ‘granular’ to allow identification, tracking, classification and response for all malaria cases (e.g. imported, introduced, indigenous).” This should lead to “subnational elimination targets as internal milestones.”

cation and development of appropriate intervention packages requires, “Excellent surveillance and response are the keys to achieving and maintaining malaria elimination; information systems must become increasingly ‘granular’ to allow identification, tracking, classification and response for all malaria cases (e.g. imported, introduced, indigenous).” This should lead to “subnational elimination targets as internal milestones.”

For high burden countries key components of Pillar 1 is, “Vector control strategies, such as use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs/LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), together with case management (prompt access to diagnosis and effective treatment) are critical for reducing malaria morbidity and mortality, and reducing malaria transmission.”

For high burden countries key components of Pillar 1 is, “Vector control strategies, such as use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs/LLINs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS), together with case management (prompt access to diagnosis and effective treatment) are critical for reducing malaria morbidity and mortality, and reducing malaria transmission.”

Recommendations like ensuring political commitment, private sector involvement and establishment of an independent advisory committee are valuable at all stages of elimination. A challenge for high burden countries will be maintaining political commitment over many years. Early involvement of the private sector will boost coverage of major interventions. An independent advisory/monitoring group will help track data and progress.

It is important to put in place good monitoring systems to ensure that program coverage is well targeted, achieved and maintained. “Systematic tracking of programme actions over time, including budget allocations and adherence to standard operating procedures.” This enables accountability and enhances political commitment.

Finally the Malaria Atlas Project has mapped most recent data, and as we can see Nigeria does have a variety of transmission settings. We know now that the decision of Nigeria’s malaria program to update its name was appropriate. Hopefully not only the NMEP but also the various state malaria programs will look at their malaria transmission strata and plan according toward elimination.

Finally the Malaria Atlas Project has mapped most recent data, and as we can see Nigeria does have a variety of transmission settings. We know now that the decision of Nigeria’s malaria program to update its name was appropriate. Hopefully not only the NMEP but also the various state malaria programs will look at their malaria transmission strata and plan according toward elimination.

ITNs &Partnership &Private Sector &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 05 Apr 2017

The Business Case for Malaria Prevention: Employer Perceptions of Workplace LLIN Distribution in Southern Ghana

Kate Klein as part of her Master of Science in Public Health program in Social and Behavioral Interventions at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health undertook a study of the potential for private sector involvement in malaria prevention in Ghana. She shares a summary of her work here. During her practicum in Ghana she was hosted by JHU’s Center for Communications Programs and its USAID supported VectorWorks Program. Her practicum she was also supported by the JHU Center for Global Health, and she presented her findings in a poster at the CGH’s Global Health Day on 30th March 2017. Her essay readers/advisers were Dr. Elli Leontsini (Department of International Health) and Kathryn Bertram (Center for Communication Programs).

Malaria is endemic in all parts of Ghana and significantly burdens families, communities, and economies. Malaria remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in Ghana; it accounts for eight percent of deaths in the country (The Global Fund, Ghana). It was also responsible for about 38% of outpatient visits, 27.3% of admissions in health facilities, and 48.5% of under-five deaths in 2015 (Nonvignon et al., 2016). In Ghana, the estimated cost of malaria to businesses in 2014 alone was estimated to be US$6.58 million, and 90% of these were direct costs (Nonvignon et al., 2016). Malaria leads to reduced productivity due to increased worker absenteeism and increased health care spending, which negatively impact business returns and tax revenue to the state (Nabyonga et al., 2011).

Although long-lasting insecticidal treated nets (LLINs) are a well-documented strategy to prevent disease in developing countries, most governments, including Ghana, lack the resources needed to comprehensively control malaria. The Global Fund (GF), USAID/President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI Ghana), and the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DfID Ghana) are the main donors for the national malaria control strategy and have worked primarily with the public sector (World Malaria Report, 2015). As government funding remains unable to close the funding gap for malaria, there is an increasing need to revitalize the private sector in sales and distribution of this life-saving technology.

A “Journey mapping” exercise to consider the process of employers buying and distributing nets to employees, created during a PSMP advocacy workshop in December 2016

Ghana is looking to the private sector to encourage a departure from previous dependence on donor-funded free bed nets. The Private Sector Malaria Prevention (PSMP at JHU) project is being implemented in Southern Ghana to increase commercial sector distribution of LLINs. Three case studies served as a situation analysis and exemplified the potential for the PSMP: a rubber producing company, a mining company and a brewery.

All three had experience in malaria control and prevention but only one had specific experience with LLINs (which dovetailed well with its own corporate strengths in logistics management as exemplified by other bottling companies in Africa). Another supported the idea of adding LLINs to its existing indoor residual spraying and community health education efforts, but needed to consider how to develop the flexibility to engage in multiple malaria interventions.

The third had had the right climate and leadership to be able to partner with PSMP, but recently underwent a takeover by a large multinational brewing company and the resulting period of transition could potentially complicate their participation in LLIN distribution efforts from a budgetary standpoint. Generally these companies had the understanding of the potential benefits to the company of situating malaria control within their structure, and thus being early candidates for adoption of the PSMP.

While the three case study companies recognized the business case for malaria, this was not a unanimous opinion among other five companies interviewed. Their concerns ranged from a preference toward treatment interventions to concerns expressed by employees about the difficulty of achieving high levels of net usage due to an array of complaints surrounding sleeping under LLINs. Some of these others had financial constraints.

While the three case study companies recognized the business case for malaria, this was not a unanimous opinion among other five companies interviewed. Their concerns ranged from a preference toward treatment interventions to concerns expressed by employees about the difficulty of achieving high levels of net usage due to an array of complaints surrounding sleeping under LLINs. Some of these others had financial constraints.

Through case studies and interviews PSMP was able to identify various challenges moving forward as well as areas where further clarity must be sought. PSMP learned that several companies are pouring their resources into strong treatment and case management programs, and one challenge will be determining how to push for preventative action, such as LLIN distribution, when treatment mechanisms are so established and bias exists.

For those companies who are making tremendous strides in malaria prevention, bringing recognition to these successes through advocacy will be necessary for encouraging future participation and convincing other similar employers of the benefits of starting their own LLIN distribution programs. Finally, PSMP needs to prioritize clarifying viewpoints on LLIN efficacy and use, with a focus on understanding why employers may hold unfavorable views and what it would take to overturn them.

In the future it will be necessary to move beyond the occupational considerations specific to mining and agro-industrial operations and consider how the work has changed the environment into a malaria habitat and the non-traditional work hours that may create more significant Anopheles mosquito exposures. PSMP should gather specific information on lifestyle, housing, and work environments during future visits with employers so that companies that have the most to gain through LLIN distribution are identified and targeted.

NTDs &Vector Control &water Bill Brieger | 22 Mar 2017

World Water Day: Water and Neglected Tropical Diseases

The United Nations introduces us to the challenges of water. “Water is the essential building block of life. But it is more than just essential to quench thirst or protect health; water is vital for creating jobs and supporting economic, social, and human development.” Unfortunately, “Today, there are over 663 million people living without a safe water supply close to home, spending countless hours queuing or trekking to distant sources, and coping with the health impacts of using contaminated water.”

Many of the infectious health challenges known as Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) have issues of water associated with their transmission. This may relate to scarcity of water and subsequent hygiene problems. It may relate to water quality and contamination. It may also relate to water in the lifecycle of vectors that carry some of the diseases.

Even though water is crucial to the control of many NTDs, it is not often the feature of large scale interventions. The largest current activity against five NTDs is mass drug administration (MDA) on an annual or more frequent basis to break the transmission cycle. Known as diseases that respond to preventive chemotherapy (PCT) through MDA, these include lymphatic filariasis (LF), trachoma, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis and soil transmitted helminths (STH) has been undertaken for over 10 years.

We have recently passed the Fifth Anniversary of the London Declaration on NTDs, which calls for the control of ten of the many these scourges The Declaration calls for “the elimination “by 2020 lymphatic filariasis, leprosy, sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis) and blinding trachoma.” Another water-borne NTD, guinea worm, should be eradicated soon. Two of the elimination targets are part of MDA efforts, LF and trachoma.

Ministries of Health and their donor and NGO partners who deliver MDA against the 5 diseases in endemic countries express interest in coordinating with water and sanitation for health (WASH) programs. People do recognize the value of collaboration between NTD MDA efforts and WASH projects, but these may be located in other ministries and organizations.

The long term implementation of WASH efforts is seen as a way to prevent resurgence of trachoma, for example, and strongly compliment efforts to control STH and schistosomiasis. Hopefully before the 10th Anniversary of the London Declaration the vision of “ensuring access to clean water and basic sanitation,” can also be achieved.

Finally as a reminder our present tools for the control of Zika and Dengue fevers relies almost entirely on safe and protected household and community sources of water to prevent breeding of disease carrying Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. If we neglect water, we will continue to experience neglected tropical diseases. Hopefully the topic of water and NTDs will feature prominently at next months global partners meeting hosted by the World Health Organization.

Borders &Elimination &Indoor Residual Spraying &Monitoring &Surveillance &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 13 Jun 2015

Moving toward Malaria Elimination in Botswana

The just concluded 2015 Global Health Conference in Botswana, hosted by Boitekanelo College at Gaborone International Convention Centre on 11-12 June provided us a good opportunity to examine how Botswana is moving toward malaria elimination. Botswana is one of the four front line malaria elimination countries in the Southern African Development Community and offers lessons for other countries in the region. Combined with the 4 neighboring countries to the north, they are known collectively as the “Elimination Eight”.

The just concluded 2015 Global Health Conference in Botswana, hosted by Boitekanelo College at Gaborone International Convention Centre on 11-12 June provided us a good opportunity to examine how Botswana is moving toward malaria elimination. Botswana is one of the four front line malaria elimination countries in the Southern African Development Community and offers lessons for other countries in the region. Combined with the 4 neighboring countries to the north, they are known collectively as the “Elimination Eight”.

The malaria elimination countries are characterised by low leves of transmission in focal areas of the country, often in seasonal or epidemic form. The pathway to malaria elimination requires that a country or defined areas in a country reach a slide positivity rates during peak malaria season of < 5%.

Chihanga Simon et al. provide us a good outline of 60+ years of Botswana’s movements along the pathway beginning with indoor residual spraying (IRS) in the 1950s. Since then the country has expanded vector control to strengthened case management and surveillance. Particular recent milestones include –

Chihanga Simon et al. provide us a good outline of 60+ years of Botswana’s movements along the pathway beginning with indoor residual spraying (IRS) in the 1950s. Since then the country has expanded vector control to strengthened case management and surveillance. Particular recent milestones include –

- 2009: Malaria elimination policy required all cases to be tested before treatment malaria elimination target set for 2015

- 2010: Malaria Strategic Plan 2010–15 using recommendations from programme review of 2009; free LLINs

- 2012: Case-based surveillance introduced

The national malaria elimination strategy includes the following:

- Focus distribution LLIN & IRS in all transmission foci/high risk districts

- Detect all malaria infections through appropriate diagnostic methods and provide effective treatment

- Develop a robust information system for tracking of progress and decision making

- Build capacity at all levels for malaria elimination

Botswana like other malaria endemic countries works with the Roll Back Malaria Partnership to compile an annual road map that identifies progress made and areas for improvement. The 2015 Road Map shows that –

- 116,229 LLINs distributed during campaigns in order to maintain universal coverage in the 6 high risk districts

- 200,721 IRS Operational Target structures sprayed

- 2,183,238 RDTs distributed and 9,876 microscopes distributed

- While M&E, Behavior Change, and Program Management Capacity activities are underway

Finally the African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA) provides quarterly scorecards on each member. Botswana is making a major financial commitment to its malaria elimination commodity and policy needs. There is still need to sustain high levels of IRS coverage in designated areas.

Finally the African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA) provides quarterly scorecards on each member. Botswana is making a major financial commitment to its malaria elimination commodity and policy needs. There is still need to sustain high levels of IRS coverage in designated areas.

Monitoring and evaluation is crucial to malaria elimination. Botswana has a detailed M&E plan that includes a geo-referenced surveillance system, GIS and malaria database training for 60 health care workers, traininf for at least 80% of health workers on Case Based Surveillance in 29 districts, and regular data analysis and feedback.

M&E activities also involve supervision visits for mapping of cases, foci and interventions, bi-annual malaria case management audits, enhanced diagnostics through PCR and LAMP as well as Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviour, and Practice surveys.

Malaria elimination activities are not simple. Just because cases drop, our job is easier. Botswana, like its neighbors in the ‘Elimination Eight’ is putting in place the interventions and resources needed to see malaria really come to an end in the country. Keep up the good work!