Children &Communication Bill Brieger | 29 Oct 2015

Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Implementation in Senegalese Children

Dr Mamadou L Diouf and colleagues[1] from the National Malaria Control Program, Dakar Senegal and the President’s Malaria Initiative/USAID, Dakar, Senegal presented their experiences with Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention among children aged 3-120 months in four southern regions of Senegal at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Their findings are outlined below.

Dr Mamadou L Diouf and colleagues[1] from the National Malaria Control Program, Dakar Senegal and the President’s Malaria Initiative/USAID, Dakar, Senegal presented their experiences with Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention among children aged 3-120 months in four southern regions of Senegal at the 64th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Their findings are outlined below.

Malaria is major cause of disease and death in infants and children, with seasonal transmission, highest in the southern and eastern regions which are the wettest areas. SMC is administration of a complete treatment course of AQ+SP at monthly intervals to a maximum of 4 doses during the malaria transmission season to children aged between 3 and 59 months in areas of highly seasonal malaria transmission (where both drugs retain sufficient antimalarial efficacy).

Target areas for implementation are areas where more than 60% of clinical malaria cases occur within a maximum of 4 months, the clinical attack rate of malaria is greater than 0.1 attack per transmission season in the target age group, and AQ+SP remains efficacious (>90% efficacy).

Target areas for implementation are areas where more than 60% of clinical malaria cases occur within a maximum of 4 months, the clinical attack rate of malaria is greater than 0.1 attack per transmission season in the target age group, and AQ+SP remains efficacious (>90% efficacy).

Adoption of SMC in 2013 as a new intervention in malaria control policy. Four south-eastern regions eligible according to WHO criteria for SMC (Tambacounda, Kédougou, Sédhiou and Kolda) chosen

The poster presented Senegal’s experience implementing SMC and focuses particularly on process, challenges and lessons learned. Available information generated from the national SMC implementation guidelines, technical documents, field activity reports, and SMC impact evaluation survey were reviewed.

The medication distribution strategy relied on a door to door campaign strategy with community volunteers. On the first day, the volunteers, trained by health workers, administer drugs to the children under surveillance of their mothers or guardians. For the 2 remaining days, mothers administer the medication.

In 2014, the SMC Campaign was conducted in the four regions for three months covering the high transmission season (August, September, October, and November). Kedougou, was the only region that conducted 2 SMC rounds as it started implementing in 2013.

In 2014, the SMC Campaign was conducted in the four regions for three months covering the high transmission season (August, September, October, and November). Kedougou, was the only region that conducted 2 SMC rounds as it started implementing in 2013.

The target was extended to children from 3 to 120 months (624,139 estimated in target age group). This age group extension, compared with WHO recommendations (3 to 60 months,) was based on shift of vulnerability towards the ages from 60 to 120 months shown by the epidemiologic data on malaria morbidity in Senegal.

Administrative coverage rates for the 3 passages respectively was 98.6%, 97.9% and 98.0%. Information was obtained from the SMC impact evaluation survey in the south of Senegal, 2015 July by Dr JL Ndiaye.

Key interventions and process began with the National and regional Steering Committees involving NMCP, health staff, donors/partners and researchers. There was development and update of tools and materials (guidelines, planning forms, data collection and analysis support. Training of staff took place at all levels and operational actors

Key interventions and process began with the National and regional Steering Committees involving NMCP, health staff, donors/partners and researchers. There was development and update of tools and materials (guidelines, planning forms, data collection and analysis support. Training of staff took place at all levels and operational actors

Early field planning was held with staff at regional and district level: identification of activities, dates, estimation of household/child targets, estimation of resources needed (budgets, HR, logistics, etc.). Early delivery of drugs, tools, supports was ensured to be available at health post level at least 1 week before the 1st campaign day.

Rigorous selection of volunteers and supervisors was based on specific criteria. Develop communications activities took place at least 2 weeks before and during the campaign period focusing on SMC gains, HH census, administration by mothers for the 2 remaining days, and possible side effects.

Campaign roll out included supervision of the process at the districts and health posts (organization model, administration). There was mobilization of logistics for transportation of volunteers, drugs, and materials. Day to day monitoring took place with regional debriefing to analyze data from districts, geographical progression, target coverage progression and identify issues and challenges. Daily electronic distribution of “SMC bulletin” to health staff and partners helped to disseminate information on districts performances.

Campaign roll out included supervision of the process at the districts and health posts (organization model, administration). There was mobilization of logistics for transportation of volunteers, drugs, and materials. Day to day monitoring took place with regional debriefing to analyze data from districts, geographical progression, target coverage progression and identify issues and challenges. Daily electronic distribution of “SMC bulletin” to health staff and partners helped to disseminate information on districts performances.

Post campaign evaluation took place at all levels: workshops for sharing and validating data and information, identification of key issues, lessons learned, and formulation of recommendations to improve future campaigns. Local health agents, NMCP staffs, partners and authorities were involved.

Spontaneous pharmacovigilance system tracked and treated side effects. This consisted of distribution of yellow cards to health facilities, case notification by health agents, availability of a side effects line listing, and immediate and free-of-charge case management.

The following key challenges were faced:

- Correct availability of drugs and tools at health posts

- Complete coverage of all households and children

- Completion of 2nd and 3rd doses by guardians of children

- Availability of children and guardians during harvest period and class time

- Comprehensive communication for population particularly in possible occurrence of side effects

- Case management of side effects free of charge

- Availability and promptness of data

- Long term logistic availability

Finally there were some outstanding questions. Can we switch SMC from campaign to routine system at health post level? Can we expand SMC to other regions and with what targets? Also, can we improve formulation and taste of drugs for enhancing children’s compliance?

Finally there were some outstanding questions. Can we switch SMC from campaign to routine system at health post level? Can we expand SMC to other regions and with what targets? Also, can we improve formulation and taste of drugs for enhancing children’s compliance?

Financial support: This work was made possible through support provided by the United States President’s Malaria Initiative, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, under the terms of an Interagency Agreement with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

[1] Dr Mamadou L Diouf, Mr Medoune Ndiop, Dr Mady Ba, Dr Ibrahima Diallo, Dr Moustapha Cisse, Dr Seynabou Gaye, Dr Alioune Badara Gueye, Dr Mame Birame Diouf

Communication &IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 28 Oct 2015

Factors associated with the uptake of malaria prophylaxis during pregnancy among female caretakers in Madagascar

Grace N. Awantang, Stella O. Babalola, Hannah Koenker, and Nan Lewicky of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Center for Communication Programs presented a poster today on IPTp uptake in Madagascar. Their Abstract follows:

Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) is one of the key interventions promoted for combatting maternal mortality and malaria. In Madagascar, supply side factors such as SP availability and ANC attendance are barriers to practicing IPTp.

Intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy (IPTp) is one of the key interventions promoted for combatting maternal mortality and malaria. In Madagascar, supply side factors such as SP availability and ANC attendance are barriers to practicing IPTp.

Less than one fifth of women (18.4%) at risk for malaria take the recommended two doses of sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (SP) to prevent malaria during pregnancy whereas about half (49.7%) visit a health provider at least four times during pregnancy. Understanding the significant predictors of IPTp2 is crucial in order to inform interventions that can effectively promote this behavior.

Prior research has shown that both communication campaigns and individual cognitive, social and emotional factors, ideation, play a role in determining other health behaviors including malaria. We examined the correlates of IPTp2 using cross-sectional household survey data collected from female caretakers of children under five years of age.

Caregiver recall of any anti-malaria messages during the past year was used to determine their exposure to health communication. Knowledge of IPTp, response-efficacy of IPTp, attitudes towards antenatal care (ANC), attitudes towards ANC, discussion of IPTp, and descriptive norm about ANC determined a person’s ideation score.

Caregiver recall of any anti-malaria messages during the past year was used to determine their exposure to health communication. Knowledge of IPTp, response-efficacy of IPTp, attitudes towards antenatal care (ANC), attitudes towards ANC, discussion of IPTp, and descriptive norm about ANC determined a person’s ideation score.

Of 1,589 female caretakers, over half (56.8%) were exposed to an anti-malarial message and a tenth (10.8%) mentioned SP as the drug used by pregnant women to prevent malaria. Message exposure, IPTp ideation and education level were all significant predictors of IPTp2 uptake in multivariate analysis.

Uptake was lowest among caretakers in the Highland transmission zone where transmission is unstable and highest in the Sub-desert transmission zone. Results suggest that both individual ideation and exposure to anti-malaria behavior change communication play a significant role in IPTp uptake among women in Madagascar.

The small portion of the variation in IPTp2 uptake explained by the measured covariates suggests that programmatic efforts should address supply-side factors that hinder access to ANC and preventive treatment of malaria during pregnancy.

Advocacy &Communication Bill Brieger | 19 Mar 2015

Leading by Example: President of Senegalese AIESEC-CESAG supports the Zero Malaria! Count Me In! campaign

Yacine Djibo, Founder & President of Speak Up Africa is helping focus International Women’s Day (March 8th) on efforts to protect women from malaria in Senegal. She is highlighting the  commitments of 8 strong and beautiful women, in Senegal, that are dedicated to eliminating malaria in their country. These commitments are part of an inclusive mass communication campaign that aims to launch a national movement in favor of malaria elimination in Senegal: the “Zero Malaria! Count Me In” campaign

commitments of 8 strong and beautiful women, in Senegal, that are dedicated to eliminating malaria in their country. These commitments are part of an inclusive mass communication campaign that aims to launch a national movement in favor of malaria elimination in Senegal: the “Zero Malaria! Count Me In” campaign

International Women’s Day, represents an opportunity to celebrate the achievements of women all around the world. This year’s theme is “Empowering Women – Empowering Humanity: Picture it” envisions a world where each woman and girl can exercise her choices, such as participating in politics, getting an education or fighting malaria. Below is the seventh feature on women fighting malaria……

Massandjé Touré is the President of Senegalese AIESEC-CESAG, a youth-led network creating positive impact through personal development and shared global experiences. The AIESEC association believes that every young person deserves the chance, and tools, to fulfill their potential, this is why it provides young people, self-driven, practical, global experiences.

As part of the Zero Malaria! Count Me In campaign, Massandjé Touré, signed the Declaration of Commitment on July 10, 2014, at the National Malaria Control Program in Senegal (NMCP), alongside the NMCP Coordinator, Dr. Mady Ba.

To further the commitment of AIESEC-CESAG, the students enrolled in the Sama Video, Sunu Santé (My video, Our Health) programme. This programme gives the opportunity to children, living in rural communities, to express themselves on their own health issues by writing and creating short films with the help of tutor. The first edition of this programme took place in the rural community of Fimela.

To further the commitment of AIESEC-CESAG, the students enrolled in the Sama Video, Sunu Santé (My video, Our Health) programme. This programme gives the opportunity to children, living in rural communities, to express themselves on their own health issues by writing and creating short films with the help of tutor. The first edition of this programme took place in the rural community of Fimela.

The second edition is now taking place in collaboration with Sup’Imax students, a higher education audiovisual school, AIESEC – CESAG students, Ibrahima Thiaw Junior High, PATH, the National Malaria Control Program and Speak Up Africa, in the frame of the Zero Malaria! Count Me In campaign.

Thank you Massandjé for leading by example and joining the Zero Malaria! Count Me In campaign and bringing awareness to all your fellow students, in Senegal and Africa.

*****

Headquartered in Dakar, Senegal, Speak Up Africa is a creative health communications and advocacy organization dedicated to catalyzing African leadership, enabling policy change, securing resources and inspiring individual action for the most pressing issue affecting Africa’s future: child health.

Communication &Ebola &Epidemic Bill Brieger | 26 Oct 2014

What the Press Tells Us about the Early Days of Liberia’s Ebola Outbreak

The mass media are assumed to play an important role in the national response to a crisis, and Ebola should be no exception. The first cases of the disease in Liberia appeared in March 2014 after victims crossed the border from its point of origin In Guinea. A search for Ebola-related articles from the early period, March to May, was undertaken in The Liberian Observer.

While to date over 1,000 articles and references on Ebola were found in The Liberian Observer, most of the news coverage has appeared from August to October. In particular there were few articles in March, a surge in April and then a tapering off in May and June, before Ebola gained more prominence in print from July onwards.

While to date over 1,000 articles and references on Ebola were found in The Liberian Observer, most of the news coverage has appeared from August to October. In particular there were few articles in March, a surge in April and then a tapering off in May and June, before Ebola gained more prominence in print from July onwards.

Generally the early news articles in the Observer report events and opinions surrounding Ebola rather than serve as direct avenues for behavior change communication (BCC). Articles on politics, science, religion, economics, social commentary and even cartoons focused indirectly or directly on key events in the development of the national response.

Because of upcoming elections politicians used the outbreak to criticize each other’s response to the problem. In the early days the economic concerns focused primarily on reduced revenues across national borders in the region. Religious leaders either tried to rally support for control through prayer and fasting or blamed the epidemic on sin.

Because of upcoming elections politicians used the outbreak to criticize each other’s response to the problem. In the early days the economic concerns focused primarily on reduced revenues across national borders in the region. Religious leaders either tried to rally support for control through prayer and fasting or blamed the epidemic on sin.

A couple opinion pieces in April acknowledged that BCC was going on through the radio. Special events such as sporting and athletics adopted an Ebola prevention theme, and several local NGOs pledged support for community outreach and awareness creation. Senators even had a retreat to learn more about the disease so they could educate their constituents.

On March 23rd Marday L Peters wrote in the Observer, As Deadly Virus Threatens Liberia, Where is the Outcry?” At least from the communications point of view, the situation improved in April.

On March 23rd Marday L Peters wrote in the Observer, As Deadly Virus Threatens Liberia, Where is the Outcry?” At least from the communications point of view, the situation improved in April.

A.M. Johnson, The Health Correspondent for the Observer reported about Health Promoters Network, Liberia (HPNL) on April 3rd, quite early in the outbreak. HPNL in expressing its support for Ministry of Health and Social Welfare efforts “urged everyone within our borders to adhere to those preventive measures such as do not eat animals that are found dead in the bush, and avoid contacts with fruit bats, monkeys, chimpanzees, antelopes and porcupines. Limit as much as possible direct contact with body fluids of infected persons or dead persons. Wash your hands with soap and water as frequently as possible.” HPNL called on other Liberian NGOs to join the cause of educating the public.

On April 20th, S. Vaanii Passewe, II mentioned in a commentary that, “… the airwaves were laden with the news of an outbreak of the deadly Ebola outbreak… Subsequent warnings from the Ministry of Health notably said that the populace should report suspected cases, refrain from coming into body contact with suspected Ebola patients, avoid shaking hands, do not have casual sex with strangers, etc. These weird precautionary measures heightened fear.”

Some actionable information was provided in regular news articles in April. For example in an article on April 25th The Observer talked about “Ending Ebola in Liberia, A Collective Approach Needed,” readers were told about the symptoms, the potential spread through fruit bats and the fact that there was no specific cure, but supportive care is needed.

Further study of more mass media outlets concerning Liberia’s Ebola control efforts is needed. We know that although an early start to educate the public was undertaken, a relative dearth of coverage in the Observer might also indicate a reduction in enthusiasm by the press, NGOs and government to sustain Ebola communication and action. For whatever reason, the epidemic spiked. Fortunately efforts are now back on track, but there is a long road ahead.

Communication &Community &Ebola Bill Brieger | 27 Sep 2014

Communication Challenges: Malaria or Ebola

The purpose of health education of behavior change communication (BCC) is to share ideas such that all sides of the communication process learn to act in ways that better control and prevent disease and promote health. Both community members (clients) and health workers (providers) need to change behavior is their interaction to become a health promoting dialogue.

This dialogue becomes easier when all parties share some common perceptions about the issue at hand. Both health workers and community members can usually agree that malaria often presents with high body temperature. Also both usually agree that malaria can be disruptive of daily life and even be deadly.

But there are differences. While both may agree that there are different types of malaria, the health worker may mention different species of Plasmodium such as falciparum, ovale, vivax, malariae and now even knowlesi. The community member may think of yellow malaria, heavy malaria, aching malaria, and ordinary malaria. These differences may put acceptance of interventions to control malaria into jeopardy. Fortunately, current downward trends in malaria incidence imply that our communicants have more in common than not.

Along comes Ebola Viral Disease in West Africa, which has killed around 3000 people in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria at this writing. The disease has never been seen on that side of the continent before. It is spreading more rapidly than it even did in its previous East and Central African outbreaks. How does one communicate with people – both community members and health workers – about a disease they have never seen before?

Along comes Ebola Viral Disease in West Africa, which has killed around 3000 people in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria at this writing. The disease has never been seen on that side of the continent before. It is spreading more rapidly than it even did in its previous East and Central African outbreaks. How does one communicate with people – both community members and health workers – about a disease they have never seen before?

The following encounter reported by BBC shows the initial confusion.

Not infrequently in the last few weeks I’ve encountered people complaining of a headache or a night of intense sweating. They slide off to the hospital and reappear a day or two later with a bag full of drugs, and they laugh it off. “Oh yeah, there are so many mosquitoes at this time of year,” they say. Better it be ‘normal’ malaria than death (Ebola).

The confusion results in harmful changes in treatment seeking behavior according to the The Pacific Northwest Conference of The United Methodist Church.

Misinformation and denial are keeping sick people from getting help. Some people are hiding from government officials and medical teams because they fear that if they go into quarantine, they will never see their loved ones again. Since the early symptoms of malaria and Ebola are similar, many malaria patients are not getting treatment. This crisis jeopardizes the progress toward improving access to health care generally.

In his blog, Larry Hollen summarizes the dilemma as follows: Both diseases disproportionately affect the poor and ill-informed Because Ebola and malaria have common early symptoms, such as fever, headache and vomiting, there may be confusion about the cause of illness among both those who are ill and health care providers.

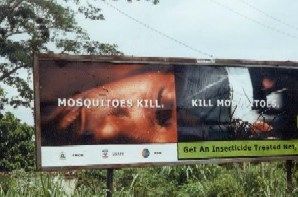

Efforts to communicate the nature and dangers of Ebola have proceeded anyway. Posters, billboards, radio spots and even local volunteers with bullhorns, armed with information from the ministries of health or NGOs remind people that Ebola can kill and that people must report to a health facility for testing and care.

This top-down approach to communication often meets skepticism and suspicion. The messages also do not match reality when people find health centers closed due to loss of staff or health workers reluctant to see febrile patients fearing that they may have Ebola, not malaria. A health education dialogue cannot take place under such circumstances.

In fact suspicion is the order of the day. Sierra Leone and Liberia have emerged not long ago from brutal civil wars that not only destroyed must health and other infrastructure but killed much of their populations and alienated those who survived. Reinforcing this suspicion and distrust are militaristic approaches in both countries to contain the poor populations most affected.

False rumors are spreading that the international donors who are slowly rallying resources to fight the disease are actually the ones who may have created and started the spread of Ebola. It is unfortunately not surprising under such circumstances that a health education team going to a remote village in Guinea were killed.

Some positive approaches to Ebola communication have been documented including the use of trusted community health workers making door-to-door visits in Sierra Leone. More effort is needed to plan a more inclusive dialogue among all parties in order to halt the Ebola epidemic. Dialogue can start from the known – like the similarities with malaria – and move into the unknown. Drugs and vaccines will not be enough, if trust and good communication are lacking.

Communication &ITNs Bill Brieger | 02 Sep 2014

Hearing, Seeing, Changing: Bednet Behavior

An important new article in Malaria Journal by colleagues at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Communications Programs gives confidence to health educators and behavior change practitioners that their interventions do make a difference. Using the 2010 Malaria Indicator Survey (MIS) from Zambia, they were able to comparing women’s reports of exposure to behavior change communication (BCC) messages and their use of insecticide treated nets (ITNs) the previous night.

Exposure to ITN messages was focused on women who “reported hearing or seeing any malaria messages in the past six months and also cited at least one specific channel: television or radio, in the newspaper, on posters or billboards, or from peer educators and drama groups.” Using two different analytic approaches, the authors found that exposure to messages was responsible for between 12-29% of net use. They concluded that the results “illustrate that BCC programmes can contribute to national programmes seeking to increase the use of ITNs inside the home.”

Exposure to ITN messages was focused on women who “reported hearing or seeing any malaria messages in the past six months and also cited at least one specific channel: television or radio, in the newspaper, on posters or billboards, or from peer educators and drama groups.” Using two different analytic approaches, the authors found that exposure to messages was responsible for between 12-29% of net use. They concluded that the results “illustrate that BCC programmes can contribute to national programmes seeking to increase the use of ITNs inside the home.”

The recent MIS in a variety of endemic countries have taken up the task of measuring not just use of ITNs but also knowledge of the role of ITNs in preventing malaria and exposure to BCC messaging about ITNs. Similar analysis should be performed on these data sets.

The 2010 Nigeria MIS, for example, reported that 27.9% of women reported exposure to malaria messages in 4 weeks prior to the study. Likewise 57.9% of women had knowledge that Sleeping under mosquito net prevents malaria in pregnancy (MIP). The 2012 MIS from Malawi reported that 25.3 women claimed exposure to malaria messages in past 4 weeks, and of those, 87.3% had knowledge that Sleeping under mosquito net prevents MIP.

The 2010 Nigeria MIS, for example, reported that 27.9% of women reported exposure to malaria messages in 4 weeks prior to the study. Likewise 57.9% of women had knowledge that Sleeping under mosquito net prevents malaria in pregnancy (MIP). The 2012 MIS from Malawi reported that 25.3 women claimed exposure to malaria messages in past 4 weeks, and of those, 87.3% had knowledge that Sleeping under mosquito net prevents MIP.

A 2011 survey in Ghana found that 57.3% of women claimed exposure to malaria messages in past 4 weeks, and of those 83.7% had knowledge that Sleeping under and ITN prevents MIP. A question remains though, what was the actual nature of those media efforts to which women claim exposure?

The surveys do note the broad sources of information, e.g. radio, health workers/clinic, community activities. A review of overall national malaria strategies and specific malaria BCC documents will certainly indicate that national programs and their partners intend to engage in a variety of BCC activities. The issue is whether, where and how those activities took place.

To give more validity to BCC outcomes, we must also encourage national malaria programs and their partners to document better their BCC activities so we can more easily attribute ITN behavior change itself to specific, funded interventions.

Communication &Treatment Bill Brieger | 27 Aug 2014

Documenting SBCC’s Important Role in Malaria Case Management

Are there examples of effective social and behavior change communication (SBCC) for malaria case management that can be shared with other countries looking to improve their programming?

After examining research, policy documents and program evaluations from Ethiopia, Rwanda, Senegal and Zambia to determine whether effective SBCC activities have been used to improve malaria case management, I haven’t come across many strong examples. Program reports don’t tend to mention SBCC program evaluation. Reports that do mention it are difficult to find credible because the indicators used don’t address the real determinants of behavior.

Behavioral researchers have spent decades trying to illustrate just how insufficient it is to measure only knowledge. Attitudinal factors like perceived risk, self-efficacy and cultural norms are important behavioral determinants conspicuously missing from reports on malaria case management program design and evaluation.

Here’s an example of an attitudinal indicator related to malaria case management: Proportion of health care service providers that believe new diagnosis and treatment guidelines (test before you treat) are effective. I found a carefully designed study (a cluster-randomized controlled trial) assessing community health workers ability to diagnose and treat children. After a brief training, health workers evaluated over a thousand children with fever and accurately treated them based on disease classification 94%-100% of the time. Of note in this study: facility-based health workers (nurses or doctors) in two districts of the Southern Province of Zambia were less likely to follow guidelines or honor the results of rapid diagnostic tests than community health workers.

MalariaCare recently conducted a series of interviews revealing the same pattern. A 2014 systematic review on malaria in pregnancy found health care provider reliance on clinical diagnosis and poor adherence to treatment policy is a consistent problem. Perhaps doctors feel their considerable experience enables them to diagnose patients accurately without policy-mandated tests? Do community health workers adhere to a policy more tightly because they have a limited number of tasks and take pride in fastidiously carrying them out? The point is that the most educated individuals in an entire country – or those most likely to have accurate, timely information – can be outperformed by individuals with little or no formal education when exposed to the exact same set of government guidelines.

The difference is attitude.

Are programs targeting the attitudinal barriers behind adherence to malaria test results? Are evaluators measuring changes in these key attitudes? You can’t measure impact if you didn’t actually change behavior and people don’t change the way they act unless their decision-making process – in all of its beautiful human complexity – is acknowledged and addressed.

The Roll Back Malaria Partnership (RBM) has an SBCC community of practice made up of public health professionals working to promote a more rigorous, evidence-based approach to malaria SBCC program design and evaluation. One of the group’s products, the Malaria Behavior Change Communication Indicator Reference Guide, was developed to help Ministries of Health, donor agencies and implementing partners design and measure levels of behavior change related to malaria prevention and case management. The guide contains a list of indicators that go beyond knowledge and awareness into important behavioral determinants like attitudes. The guide has been available since February 2014 and this month the group is happy to announce its publication in Portuguese (it is also available in French and English).

The answer to the question posed by this desk review is that there is a lot of great work being done in malaria case management but it is being in done in a way that makes it difficult for others to follow. This new tool was developed to ensure SBCC programming is designed in such a way that its impact can be measured and replicated.

Communication &Community Bill Brieger | 29 Jul 2014

Journal of Indigenous and Community Communication (JICC)

Colleagues at the University of Ibadan have started on an important publishing endeavor as described below. Indigenous communication is an often neglected aspect of behavior change communication, and we hope this new Journal will bring more attention on how we can communicate about important health issues like malaria in ways that make sense to the community. Of course we also need to be willing to learn from the community first about their perceptions in order to have effective two-way communication:

Call for Papers for the Maiden Edition

The Editorial Board of the Journal of Indigenous and Community Communication (JICC) hereby invites original research articles, (empirical and discursive/expository), for the maiden edition of the journal that will be published in December 2014. JICC aims at offering space for scholars, researchers and development practitioners to contribute both qualitative and quantitative research findings in form of case studies, community-based situation analysis, reports of community-based interventions, evidence-based policy suggestions and intervention measures, and policy briefs. This volume will explore the theme of Community Communication and Poverty Reduction in Africa, with particular reference to the voices from community’s grassroots.

The Editorial Board of the Journal of Indigenous and Community Communication (JICC) hereby invites original research articles, (empirical and discursive/expository), for the maiden edition of the journal that will be published in December 2014. JICC aims at offering space for scholars, researchers and development practitioners to contribute both qualitative and quantitative research findings in form of case studies, community-based situation analysis, reports of community-based interventions, evidence-based policy suggestions and intervention measures, and policy briefs. This volume will explore the theme of Community Communication and Poverty Reduction in Africa, with particular reference to the voices from community’s grassroots.

From recent researches,[1] the number of people living in absolute poverty in Africa is still high compared to most other low-income regions. Reasons given for the soaring numbers are diverse, ranging from leadership, irrelevant policies, failing institutions, human geography, among others. There are however many success stories from different African countries, stories that hardly get to find audience at the national and international levels, stories of people who through their daily struggle contribute to their betterment of their livelihoods.

This maiden edition is dedicated to how the community grassroots’ communication mechanisms contribute towards alleviating absolute poverty for those involved. Contributions to this edition should therefore centre on the efforts of knowledge and idea transfer at the very community’s basic level. Key questions around this focus include: In what ways do individuals get to exchange ideas about their own, and community’s development? Who takes initiative in the transfer of these ideas, and what informs this initiative? How (in)effective are these modes of communication? How can these grassroots, community-based communication initiatives become more widely accepted and engaged in dealing with poverty issues in African communities? What are the implications of these modes of indigenous/community-based communications with regards to reducing poverty in Africa?

Articles that explore these and other related questions, and especially field researches that are innovative and original are welcome.

Abstract submission

The first stage is to submit an abstract of a maximum of 300 words. In the abstract, indicate the gap that exists in literature and/or the key research question. It is important to link the key question to poverty and communication. Include the area (geographical) specificity of research in the case of empirical data and methodology, and how the findings will be useful in addressing/answering your research question. Include your name, institutional affiliation and email address. Once the editors have reviewed the abstracts, authors whose abstracts are accepted will be contacted to submit full papers. The deadline for abstract submission is August 10 2014. The abstracts should be submitted to: ayo.ojebode@mail.ui.edu.ng and mbusupa@yahoo.com

Article submission

Full articles should be written using the APA 6th style referencing. The words should be limited to 7,000 including footnotes and list of references (avoid providing bibliography). Briefings and policy briefs that provide review of specific country’s topical issues should be limited to a maximum of 3,000 words. Book reviews that are relevant to the theme of the edition should not exceed 1,000 words. Full articles for this volume are due November 15 2014.

JICC does not accept articles that are under consideration by other publishers. JICC does not compromise on matters of ethics and integrity. All academic articles will be peer-reviewed blind by three reviewers. An article is not recommended for revision unless it has at least two positive reviews. Two reviewers will review briefs and reports by organisations working in communities. JICC also strives to ensure that reviewers’ reports are turned in within six weeks. JICC conducts plagiarism checks on each article submitted to it. Any article that fails the test will be rejected and the author(s) will be barred from publishing in JICC in future.

JICC will be published availed online and in print.

Funding and Outlet

The Nigerian Community Radio Coalition supports JICC. However, we welcome support from other institutions and individuals in Africa and beyond.

JICC Editorial Board:

- Dr. Ayobami Ojebode – University of Ibadan, Nigeria

- Dr. Susan M. Kilonzo – Maseno University, Kenya

- Dr. Tunde Adegbola – African Languages Technology Initiative, ALT-I, Nigeria

- Prof. Holger Briel – Xi’an Jiaotong Liverpool University, Suzhou, China

- Prof. Kitche Magak – Maseno University, Kenya

- Prof. Christopher J. Odhiambo – Moi University, Kenya

- Dr. Birgitte Jallov – Empowerhouse, Denmark

- Ms. Jackline A. Owacgiu – Uganda/London School of Economics

[1]See for example Collier, P. Poverty reduction in Africa. Accessible at http://users.ox.ac.uk/~econpco/research/pdfs/PovertyReductionInAfrica.pdf. Collier’s book-The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be done about it. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, explores this further.

Communication &Education Bill Brieger | 19 May 2014

Educating the Media on Malaria Control

The mass media – electronic, print and now social – play an important role in the fight against malaria. The media reach diverse audiences from villagers to policy makers. Because of their potential influence, the media must have the story right when it comes to malaria.

A news story published online this morning from a highly malaria-endemic country shows how some subtle but important mistakes can give wrong impressions and lead to wrong actions. The fact that the information is attributed to “medical science experts” does not mean that the reporters quoted them in the correct context.

A news story published online this morning from a highly malaria-endemic country shows how some subtle but important mistakes can give wrong impressions and lead to wrong actions. The fact that the information is attributed to “medical science experts” does not mean that the reporters quoted them in the correct context.

The first example from the story is, “Spending on malaria and dengue fever treatment programmes should be controlled, with more efforts directed to preventive measures …” As a disease caused by a virus, dengue does not have a definitive treatment, if by treatment we mean a cure.

Life saving palliative care is important in dengue, but dengue in Africa usually goes undiagnosed and is unfortunately often treated by wasting malaria drugs. The issue is not reducing treatment funds, but using rapid diagnostic tests so that we will not waste our expensive malaria medicines on non-malarial fevers.

The article next talks about how scientists in the country, “are advising the government to authorise controlled use of the banned pesticide DDT to strengthen mosquito eradication and bite control programmes in the country.” DDT has been used for indoor residual spraying against the malaria carrying anopheles mosquitoes. This fits into the anopheles behavior of resting on walls after biting.

By contrast dengue is carried by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. They are the ones that breed in pots, tins, etc. around the house, and DDT is not a major part of the efforts to control them. Household members are responsible for removing or not even allowing such small collections of water to occur in their houses, on their property and among their neighbors.

A final odd claim is that, “Donor funded health programmes are disadvantaged because the in-country implementers ‘accept each and every thing directed to them by the donors without challenging their ideas.’” For the biggest malaria funding programs this is not true. The Global Fund for years has required that countries submit their own proposals that were developed and passed through their own national country coordinating mechanisms.

Now Global Fund is requiring countries to submit their own national malaria strategies as a basis for funding. The Global Fund is a financial organization, not a technical one, and thus is not directing countries what to do other that spend their money well on scientifically sound interventions.

Other donors work together with national malaria control programs and their partners to develop country specific and relevant operational plans. Donors do encourage countries to implement scientifically proven guidance that is developed by international technical committees whose members include scientists from endemic countries.

The points above could create unfortunate misunderstandings by the public (about insecticides), professionals (about treatment) and policy makers (about donor support). The media should foster appropriate and timely action against malaria, not confuse the public.

Advocacy &Communication &Community &Health Systems Bill Brieger | 03 Jan 2014

Behavior Change for Malaria: Are We Focusing on the Right ‘Targets’

Two articles caught my attention this morning. One reviewed the merits of improved social and behavior change communication (BCC) for the evolving malaria landscape. The other addressed the damage institutional corruption is doing in Africa. And yes, there is a connection.

When I was trained as a community or public health educator in the MPH program at UNC Chapel Hill, the term BCC had not yet been coined. We were clearly focused on human behavior and health. What was especially interesting about the emphasis of that program was the need to cast a wide net on the human beings whose behaviors influence health.

While the authors in Malaria Journal state that, “The purpose of this commentary is to highlight the benefits and value for money that BCC brings to all aspects of malaria control, and to discuss areas of operations research needed as transmission dynamics change,” a closer look shows that the behaviors of interest are those of individuals and communities who do not consistently use bed nets, delay in seeking effective treatment, and do not take advantage of the the distribution of intermittent preventive therapy (IPTp) during pregnancy. The shortfalls in the behavior of other humans is lies in not “fully explaining” these interventions to community members.

The health education (behavior change, communications, etc. etc.) program at Chapel Hill taught us that a comprehensive intervention included not only means and media for reaching the community, but also processes to train health workers to perform more effectively, to advocate with policy makers to adopt and fund health programs, and intervene in the work environment using organizational change strategies to ensure programs actually reached people whose adoption of our interventions (nets, medicines) could improve their health.

At UNC we tried to focus change on all humans in the process from health staff to policy makers to ensure that we would not be blaming the community for failing to adopt programs that were not made appropriately accessible and available to them. We did not call it a systems approach then, but clearly it was.

This brings me back to the article on corruption. Let’s compare these two quotes from the IRIN article …

- The region accounts for 11 percent of the world’s population, but carries 24 percent of the global disease burden. It also bears a heavy burden of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria but lacks the resources to provide even basic health services.

- Poor public services in many West African countries, with already dire human development indicators, are under constant pressure from pervasive corruption. Observers say graft is corroding proper governance and causing growing numbers of people to sink into poverty.

Illicit cash transfers out of countries and bribery of civil servants, including health workers, are manifestations of the same problem at different ends of the spectrum resulting in less access to basic services and health commodities. Continued national Demographic and Health Surveys show that well beyond 2010 when the original Roll Back Malaria Partnership coverage targets of 80% were supposed to have been achieved, we see few malaria endemic countries have achieved the basics, and some have regressed. Everyone is bemoaning the lack of adequate international funding for malaria (and HIV and TB and NTDs), but what has happened with the money already spent?

Without a systems approach to health behavior and efforts by development partners to hold all those involved accountable, we cannot expect that the behavior of individuals and communities will win the war against malaria.