Epidemiology &History &Migration &Mosquitoes &Plasmodium/Parasite Bill Brieger | 12 Oct 2019

What to Observe on October 12th? Malaria’s Arrival in the Americas

Controversy exists about what historical event should be observed in the USA on 12th October. Ernest Faust explained many years ago that, “there is neither direct nor indirect evidence that the malaria parasites existed on this continent prior to the advent of the European conquerors,” while at the same time in the 16th through 18th Centuries, malaria  was common in England, Spain, France, Portugal and other European nations that arrived in the “New World.” Initially, with the first voyage of Columbus the European explorers and settlers brought the disease, primarily Plasmodium vivax, while the slave trade brought P. falciparum.

was common in England, Spain, France, Portugal and other European nations that arrived in the “New World.” Initially, with the first voyage of Columbus the European explorers and settlers brought the disease, primarily Plasmodium vivax, while the slave trade brought P. falciparum.

National Geographic in its May 2007 issue provided the story “Jamestown, The Real Story.” This article reported that, “Colonists carried the plasmodium parasite to Virginia in their blood. Mosquitoes along the Chesapeake were ‘infected’ by the settlers and spread the parasite to other humans.” Thus malaria became one of many imported diseases that decimated the indigenous population. The spread of P. vivax in Jamestown was not surprising since the settlement was “located on marshy ground where mosquitoes flourished during the summer.”

Recent research has shown that the “Analysis of genetic material extracted showed that the American P. falciparum parasite is a close cousin of its African counterpart.” This research has documented two genetic groups in Latin America, related to two distinct slave routes run by the Spanish empire in the North, West Indies, Mexico and Colombia and the Portuguese empire to Brazil. Indigenous and remote rural populations of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela and Brazil remain at risk today.

Recent research has shown that the “Analysis of genetic material extracted showed that the American P. falciparum parasite is a close cousin of its African counterpart.” This research has documented two genetic groups in Latin America, related to two distinct slave routes run by the Spanish empire in the North, West Indies, Mexico and Colombia and the Portuguese empire to Brazil. Indigenous and remote rural populations of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela and Brazil remain at risk today.

In the South American continent the native American population might have brought Melanesian strains of P. vivax before the Europeans arrived, but colonizers brought new strains from both Europe and Africa, as well as P. falciparum. Clearly, human migration has played an important role in malaria parasite dissemination through the Americas.

But back to the North American Continent where the USA is observing the historical implications of 12th October, Mark Blackmore reminds us that, “Anthropological and archeological data provide no indication of mosquito-borne diseases among the indigenous people of North America prior to contact with Europeans and Africans beginning in the fifteenth century” (Wing Beats Volume 25 Winter 2015). The spread of malaria by European colonizers is certainly not something to celebrate today.

Asymptomatic &Elimination &Eradication &Monkeys &Mosquitoes &Resistance &Vaccine Bill Brieger | 23 Aug 2019

Biology and Malaria Eradication: Are there Barriers?

During a press conference prior to the release of the executive summary of 3-year study of trends and future projections for the factors and determinants that underpin malaria by its Strategic Advisory Group on Malaria Eradication (SAGme), WHO outlined some hopeful signs emanating from the SAGme including

- Lack of biological barriers to malaria eradication

- Recognition of the massive social and economic benefits that would provide a return on investment in eradication, and

- Megatrends in the areas of factors such as land use, climate, migration, urbanization that could inhibit malaria transmission

Concerning the first point, the executive summary notes that, “We did not identify biological or environmental barriers to malaria eradication. In addition, our review of models accounting for a variety of global trends in the human and biophysical environment over the next three decades suggest that the world of the future will have much less malaria to contend with.”

Concerning the first point, the executive summary notes that, “We did not identify biological or environmental barriers to malaria eradication. In addition, our review of models accounting for a variety of global trends in the human and biophysical environment over the next three decades suggest that the world of the future will have much less malaria to contend with.”

The group did agree that, “using current tools, we will still have 11 million cases of malaria in Africa in 2050.” So one wonders whether there are biological barriers or not.

Interestingly the group did identify, “Potential biological threats to malaria eradication include development of insecticide and antimalarial drug resistance, vector population dynamics and altered vector behaviour. For example, Anopheles vectors might adapt to breeding in polluted water, and mosquito vector species newly introduced to Africa, such as Anopheles stephensi, could spread more widely into urban settings.”

This discussion harkens back to an important conceptual article by Bruce Aylward and colleagues that raised the question in the American Journal of Public Health, “When Is a Disease Eradicable?” They outlined three important criteria that had been proposed at two international conferences in 1997 and 1998.

- biological and technical feasibility

- costs and benefits, and

- societal and political considerations

Their further expansion on the biological issues using smallpox as an example is instructive. They noted that not only are humans essential for the life cycle of the organism, but that there was no other reservoir for the causative virus, and the virus could not amplify in the environment. In short, there were no vectors, as in the case of malaria. The relatively recent documentation of transmission of malaria between humans and other primates of different plasmodium species is another biological concern. At this point, Malaysia, for example, is reporting more cases of Plasmodium knowlesi in humans that either P vivax or P falciparum.

Another biological issue identified by Aylward and colleagues was the fact that smallpox had one effective and proven intervention, the vaccine. Application of the vaccine could be targeted using photograph disease recognition cards as the signs were quite specific to the disease. Malaria has several effective interventions, but most strategies emphasize the importance of using a combination of these, and implementation is met with a number of management and logistical challenges. The signs and symptoms of malaria are confused with a number of febrile illnesses.

Finally, two other issues raised concern. Insecticide resistance was recognized in the first malaria eradication effort, and is raising its head again, as pointed out by SAGme. Comparing smallpox and yaws, the challenge of latent or sub-clinical/asymptomatic infection was mentioned. Malaria too, is beleaguered with this problem.

Clearly, we must not lose momentum in the marathon (not a race) to eliminate malaria, but we must, as WHO stressed at the press conference, increase our research and development efforts to strengthen existing tools and develop new once to address the biological and logistical challenges.

Borders &Diagnosis &Ebola &Elimination &Integrated Vector Management &ITNs &Mosquitoes &NTDs &Snakebite &Trachoma &Urban Bill Brieger | 04 Aug 2019

Tropical Health Update 2019-08-04: Ebola, Malaria Vectors, Snakebite and Trachoma

In the past week urban transmission in Goma, a city of at least 2 million inhabitants in eastern Democratic republic of Congo, was documented as a gold miner came home and infected his wife and child. To get a grip on the spread of the disease, DRC is considering another vaccine, not without some controversy. WHO provides detailed guidance on all aspects of response. On the malaria front we have learned more about malaria vectors, natural immunity and reactive case detection.

Ebola Challenges: Vaccines, Urban Transmission

The current Ebola vaccine being deployed to over 150,000 people in North Kivu and Ituri Provinces was itself an experimental intervention during 2016 when it was first used in the largest ever outbreak located in West Africa. BBC reports that, “World Health Organization (WHO) data show the Merck vaccine has a 97.5% efficacy rate for those who are immunised, compared to those who are not.”

The current Ebola vaccine being deployed to over 150,000 people in North Kivu and Ituri Provinces was itself an experimental intervention during 2016 when it was first used in the largest ever outbreak located in West Africa. BBC reports that, “World Health Organization (WHO) data show the Merck vaccine has a 97.5% efficacy rate for those who are immunised, compared to those who are not.”

The proposed addition of a Johnson and Johnson vaccine would be in that same experimental phase if introduced in DRC now. It has been proven safe as well as effective in other primates. The challenge is that even though the Merck vaccine supplies are near 500,000, this is not enough to cover the potential needs in an area with over 10 million people, although Merck is still producing more. At present, BBC says, “Those pushing for the use of the new Johnson & Johnson vaccine, had proposed using it to create a protective wall, vaccinating people outside the outbreak zone.” In addition, the new national response team is concerned that “Only about 50% of cases of Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo are being identified.”

Finally, there is the issue of community mistrust of government workers and challenging logistics. “There are also concerns that the new vaccine – which requires two injections 56 days apart – may be difficult to administer in a region where the population is highly mobile, and insecurity is rife.”

If efforts at vaccination are needed soon in Goma, up to 2 million doses might be needed. Reuters reports that, “Congolese authorities were racing to contain an Ebola epidemic on Thursday, after a gold miner with a large family contaminated several people in the east’s main city of Goma before dying of the hemorrhagic fever.” Readers may recall that the West Africa outbreak of 2014-16 in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia accelerated greatly after infected people went to major cities in search of help.

The miner is the second ‘imported case into Goma, which borders Rwanda, but because his family lives there, he has already infected his wife and one of his 10 children. Contacts are being traced and monitored, but this urban and border threat is one of the factors that led WHO to finally declare the current outbreak a public health emergency.

Malaria

As we move toward malaria elimination Reactive Case Detection (RCD) has been proposed as an integral part of these efforts with the hopes that is can be conceived of as a way of gradually decreasing transmission, according to an article in Malaria Journal. In fact, the value of RCD may be limited as follows:

- RCD alone can eliminate malaria in only a very limited range of settings, where transmission potential is very low

- In other settings, it is likely to reduce disease burden and help maintain the disease-free state in the face of imported infections

Another article looks at “natural exposure to gametocytes that can result in the development of immunity against the gametocyte by the host as well as genetic diversity in the gametocyte.” The researchers learned that there can be variations in immune response depending on season and geography. This information is helpful in planning malaria elimination interventions.

On the vector front a baseline susceptibility testing was conducted in 16 countries in sub-Saharan Africa for neonicotinoids. “The target site of neonicotinoids represents a novel mode of action for vector control, meaning that cross-resistance through existing mechanisms is less likely.” The findings will help in the preparation for rollout of clothianidin formulations as part of national IRS rotation strategies by PMI and other partners.

Researchers also called on us to learn more about malaria vectors in other parts of the world. In order to eliminate Plasmodium falciparum from the Caribbean and Central America program planners should consider local vector characteristics such as An. albimanus. They found that, “House-screening and repellent IRS are potentially highly effective against An. albimanus if people are indoors during the evening.”

Researchers also called on us to learn more about malaria vectors in other parts of the world. In order to eliminate Plasmodium falciparum from the Caribbean and Central America program planners should consider local vector characteristics such as An. albimanus. They found that, “House-screening and repellent IRS are potentially highly effective against An. albimanus if people are indoors during the evening.”

Vectors are also of concern on the edges of malaria transmission, particularly in South Africa, one of the ‘elimination eight’ countries of the Southern Africa Development Community. Researchers examined the, “potential role of Anopheles parensis and other Anopheles species in residual malaria transmission, using sentinel surveillance sites in the uMkhanyakude District of northern KwaZulu-Natal Province.” They found Anopheles parensis is a potential but minimal vector of malaria in South Africa “owing to its strong zoophilic tendency.” On the other hand, An. arabiensis was found to be the major vector responsible for residual malaria transmission in South Africa. Since these mosquitoes were found in outdoor-placed resting traps, interventions are needed to control outdoor-resting of vector populations.

NTDs of Concern

During the week, the member states of the African Union renewed their commitment to fight and permanently eliminate Neglected Tropical Diseases. Africa.com reported that, “Achievements to date include 1 billion people treated against at least one NTD and 37 countries have completed the removal of at least one NTD.”

Although some reports have discounted the idea of trachoma in Namibia, there may be reason to re-examine the situation. On Twitter Anthony Solomon notes that Namibia needs #trachoma prevalence surveys. A just-completed joint Ministry of Health & Social Services/@WHO mission found active trachoma & trichiasis in Zambezi & Kunene Regions.

The Times of India draws attention to snakebite. It says that “Under-reported and inadequately treated, fatalities in India are estimated at close to 50,000 a year, the world’s highest.”

The Times of India draws attention to snakebite. It says that “Under-reported and inadequately treated, fatalities in India are estimated at close to 50,000 a year, the world’s highest.”

Overall we can see that the concept of ‘neglect’ has several uses. There is neglect if half of Ebola cases are undetected. There is neglect if we do not understand malaria vectors in low transmission areas. Finally, there is neglect if we do not conduct up-to-date disease surveys to determine whether a disease is present or not. Elimination of tropical diseases is challenging when key processes are neglected.

Conflict &Diagnosis &Ebola &ITNs &Mosquitoes &Plasmodium/Parasite &Resistance &Vaccine Bill Brieger | 29 Jul 2019

Tropical Health Update 2019-07-28: Ebola and Malaria Crises

This posting focuses on Malaria and Ebola, both of which have been the recent focus of some disturbing news. The malaria community has been disturbed by the clear documentation of resistance to drugs in Southeast Asia. Those working to contain Ebola in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of Congo saw a change in political leadership even in light of continued violence and potential cross-border spread.

Malaria Drug Resistance

Several sources reported on studies in the Lancet Infectious Diseases concerning the spread of Multidrug-Resistant Malaria in Southeast Asia. Reuters explained that by sing genomic surveillance, researchers concurred that “strains of malaria resistant to two key anti-malarial medicines are becoming more dominant” and “spread aggressively, replacing local malaria parasites,” becoming the dominant strains in Vietnam, Laos and northeastern Thailand.”

The focus was on “the first-line treatment for malaria in many parts of Asia in the last decade has been a combination of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine, also known as DHA-PPQ,” and resistance had begun to spread in Cambodia between 2007 and 2013. Authors of the study noted that while, “”Other drugs may be effective at the moment, but the situation is extremely fragile, and this study highlights that urgent action is needed.” They further warned of an 9impending Global Health Emergency.

The focus was on “the first-line treatment for malaria in many parts of Asia in the last decade has been a combination of dihydroartemisinin and piperaquine, also known as DHA-PPQ,” and resistance had begun to spread in Cambodia between 2007 and 2013. Authors of the study noted that while, “”Other drugs may be effective at the moment, but the situation is extremely fragile, and this study highlights that urgent action is needed.” They further warned of an 9impending Global Health Emergency.

NPR notes that “Malaria drugs are failing at an “alarming” rate in Southeast Asia” and provided some historical context about malaria drug resistance arising in this region since the middle of the 20th century. “Somehow antimalarial drug resistance always starts in that part of the world,” says Arjen Dondorp, who leads malaria research at the Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit in Bangkok and who was a lead author of the report about the randomized trial. Ironically, “one reason could have something to do with the relatively low levels of malaria there. When resistant parasites emerge, they are not competing against a dominant nonresistant strain of malaria and are possibly able to spread easier.

When we are talking about monitoring resistance in low resource and logistically and politically challenging areas, we need to think of appropriate diagnostic tools at the molecular level. Researchers in Guinea-Bissau conducted a proof of concept study and used malaria rapid diagnostic tests applied for parallel sequencing for surveillance of molecular markers. While they noted that, “Factors such as RDT storage prior to DNA extraction and parasitaemia of the infection are likely to have an effect on whether or not parasite DNA can be successfully analysed … obtaining the necessary data from used RDTs, despite suboptimal output, becomes a feasible, affordable and hence a justifiable method.”

A Look at Insecticide Treated Nets

On a positive note, Voice of America provides more details on the insecticide treated net (ITN) monitoring tool developed called “SmartNet” by Dr Krezanoski in collaboration with the Consortium for Affordable Medical Technologies in Uganda. The net uses strips of conductive fabric to detect when it’s in use. Dr. Krezanoski was happy to find that people given the net used it no differently that if they were not being observed. The test nets made it clear who what using and not using this valuable health investment and when it was in use. Such fine tuning will be deployed to design interventions to educate net users based on their real-life use patterns.

Another important net issue is local beliefs that may influence use. We can find out when people use nets, but we also need to determine why. In Tanzania, researchers found that people think mosquitoes that bite in the early evening when people are outside relaxing are harmless. As one community member said, “I only fear those that bite after midnight. We’ve always been told that malaria is spread by mosquitoes that bite after midnight.”

Even if people do use their ITNs correctly, we still need to worry about insecticide resistance. A study in Afghanistan reported that, “Resistance to different groups of insecticides in the field populations of An. stephensi from Kunar, Laghman and Nangarhar Provinces of Afghanistan is caused by a range of metabolic and site insensitivity mechanisms.” The authors conclude that vector control programs need to be better prepared to implement insecticide resistance management strategies.

Ebola Crisis Becomes (More) Political

Headlines such as “Congo health minister resigns over response to Ebola crisis” confronted the global health community this week. this happened after the DRC’s relatively new president took control of the response. The President set up a new government office to oversee the response to an outbreak outside of the Ministry of Health which was managing the current outbreak and the previous ones. The new board was set up without the knowledge of the Minister who was traveling to the effected provinces at the time.

The former Minister, Dr Oly Ilunga stated on Twitter that, “Suite à la décision de la @Presidence_RDC. de gérer à son niveau l’épidémie d’#Ebola, j’ai remis ma démission en tant que Ministre de la Santé ce lundi. Ce fut un honneur de pouvoir mettre mon expertise au service de notre Nation pendant ces 2 années importantes de notre Histoire. (Following the decision of the @Presidence_RDC to manage the # Ebola outbreak, I resigned as Minister of Health on Monday. It was an honor to be able to put my expertise at the service of our Nation during these two important years of our History.)

The former Minister, Dr Oly Ilunga stated on Twitter that, “Suite à la décision de la @Presidence_RDC. de gérer à son niveau l’épidémie d’#Ebola, j’ai remis ma démission en tant que Ministre de la Santé ce lundi. Ce fut un honneur de pouvoir mettre mon expertise au service de notre Nation pendant ces 2 années importantes de notre Histoire. (Following the decision of the @Presidence_RDC to manage the # Ebola outbreak, I resigned as Minister of Health on Monday. It was an honor to be able to put my expertise at the service of our Nation during these two important years of our History.)

The former Minister also warned that the “Multisectoral Ebola Response Committee would interfere with the ongoing activities of national and international health workers on the ground in North Kivu and Ituri provinces.” Part of the issue may likely have been “pressure to approve a new vaccine in addition to one that has already been used to protect more than 171,000 people.” People had warned about the potential confusion to the public as well as ethical issues if a second vaccine was used, especially one that did not have the strong accumulated evidence from both the current outbreak as well as the previous one in West Africa.

The former Minister also warned that the “Multisectoral Ebola Response Committee would interfere with the ongoing activities of national and international health workers on the ground in North Kivu and Ituri provinces.” Part of the issue may likely have been “pressure to approve a new vaccine in addition to one that has already been used to protect more than 171,000 people.” People had warned about the potential confusion to the public as well as ethical issues if a second vaccine was used, especially one that did not have the strong accumulated evidence from both the current outbreak as well as the previous one in West Africa.

One might have thought that this would be a time when stability was needed since “The WHO earlier this month declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern, a rare step meant to highlight the urgency of the moment that has been used only four times before.” In addition, “the World Bank said it would release $300 million from a special fund set aside for crises like viral outbreaks to help cover the cost of the response.”

Unfortunately one of the msain impediments to successful Ebola control, violence in the region, continues. CIDRAP stated that. “the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a rebel group, attacked two villages near Beni, killing 12 people who live in the heart of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC’s) ongoing Ebola outbreak. The terrorists killed nine in Eringeti and three in Oicha, according to Reuters. ADF has not publicly pledged allegiance to the Islamic state (ISIL), but that hasn’t stopped ISIL from claiming responsibility for the attacks.” It will take more than a change of structure in Kinshasa to deal with the realities on the ground.

CIDRAP also observed that since the resignation of the Health Minister, “DRC officials have provided no update on the outbreak, including statistics on the number of deaths, health workers infected, or suspected cases.” The last was seen on 21 July 2019.

CIDRAP also observed that since the resignation of the Health Minister, “DRC officials have provided no update on the outbreak, including statistics on the number of deaths, health workers infected, or suspected cases.” The last was seen on 21 July 2019.

ReliefWeb reports that, “Adding to the peril, the Ebola-affected provinces share borders with Rwanda and Uganda, with frequent cross-border movement for personal travel and trade, increasing the chance that the virus could spread beyond the DRC. There have already been isolated cases of Ebola reported outside of the outbreak zone.”

These are troubling times when parasites and mosquitoes are becoming more resistant to our interventions and when governments and communities are resistant to a clear and stable path to disease containment and control.

Agriculture &Borders &Ebola &Essential Medicines &Integrated Vector Management &ITNs &Larvicide &Mosquitoes &Schistosomiasis &Severe Malaria &Vaccine &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 15 Jul 2019

The Weekly Tropical Health News 2019-07-13

In the past week more attention was drawn to the apparently never-ending year-long Ebola outbreak in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Regarding other diseases, there is new information on the RTS,S malaria vaccine, river prawns have been found to play a biological control role in schistosomiasis, and an update from the World Health Organization on essential medicines and diagnostics. New malaria vector control technologies are discussed.

Second Largest Ebola Outbreak One Year On

Ronald A. Klain and Daniel Lucey in the Washington Post observed raised concern that, “the disease has since crossed one border (into Uganda) and continues to spread. In the absence of a trajectory toward extinguishing the outbreak, the opposite path — severe escalation — remains possible. The risk of the disease moving into nearby Goma, Congo — a city of 1 million residents with an international airport.”

They added their voices to a growing number of experts who are watching this second biggest Ebola outbreak in history and note that, “As the case count approaches 2,500 with no end in sight, it is time for the WHO to declare the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern — a ‘PHEIC’ — to raise the level of global alarm and signal to nations, particularly the United States, that they must ramp up their response.” They call for three actions: 1) improved security for health workers in the region, 2) stepped up community engagement and 3) extended health care beyond Ebola treatment. The inability to adequately respond to malaria, diarrheal diseases and maternal health not only threated life directly, but also threated community trust, putting health workers’ lives at risk.

Olivia Acland, a freelance journalist based in DRC, reporting for the New Humanitarian describes the insecurity and the recent “wave of militia attacks in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s northeastern Ituri province has left hundreds dead and roughly 300,000 displaced in recent weeks, triggering a new humanitarian crisis in a region.” Specifically, “Ituri, a fertile region rich in gold deposits, has been an epicentre of conflict in Congo for decades. Between 1999 and 2003, around 60,000 people were killed here, as a power struggle between rebel groups escalated into ethnic violence,” related to traditional tensions between Hema cattle herders and Lendu farmers with roots in Belgian colonization.

Updates from the DRC Ministry of Health report on average 11 new Ebola cases per day in the past week. So far over 160,000 people have been vaccinated, and yet the spread continues. The Ministry also describes new protocol contains three vaccinations strategies that can be used depending on the environment in which confirmed cases are found including:

- Classic Ring: The classic strategy of vaccinating contacts of confirmed cases and contact contacts.

- Enlarged ring: It is also possible to vaccinate all inhabitants of houses within 5 meters around the outbreak of a confirmed case.

- Geographical Ring: In an area where team safety can not be guaranteed, they can vaccinate an entire village or neighborhood.

Malaria Vaccines, Essential Drugs and New Vector Control Technologies

Halidou Tinto and colleagues enrolled two age groups of children in a 3-year extension of the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine efficacy trial: 1739 older children (aged 5–7 years) and 1345 younger children (aged 3–5 years). During extension, they reported 66 severe malaria cases. Overall they found that, “severe malaria incidence was low in all groups, with no evidence of rebound in RTS,S/AS01 recipients, despite an increased incidence of clinical malaria in older children who received RTS,S/AS01 compared with the comparator group in Nanoro. No safety signal was identified,” as seen in The Lancet.

WHO has updated the global guidance on medicines and diagnostic tests to address health challenges, prioritize highly effective therapeutics, and improve affordable access. Section 6.5.3 presents antimalarial medicines including curative treatment (14 medicines) for both vivax and falciparum and including tablets and injectables. Prophylaxis includes 6 medicines including those for IPTp and SMC. The latest guidance can be downloaded at WHO.

Paul Krezanoski reports on a new technology to monitor bednet use and tried it out in Ugandan households. As a result. “Remote bednet use monitors can provide novel insights into how bednets are used in practice, helping identify both households at risk of malaria due to poor adherence and also potentially novel targets for improving malaria prevention.

In another novel technological approach to vector control, Humphrey Mazigo and co-researchers tested malaria mosquito control in rice paddy farms using biolarvicide mixed with fertilizer in Tanzanian semi-field experiments. The intervention sections (with biolarvicide) had lowest mean mosquito larvae abundance compared to control block and did not affect the rice production/harvest.

Prawns to the Rescue in Senegal Fighting Schistosomiasis and Poverty

Anne Gulland reported how Christopher M. Hoover et al. discovered how prawns could be the key to fighting poverty and schistosomiasis, a debilitating tropical disease. They found that farming the African river prawn could fight the disease and improve the lives of local people, because the African river prawn is a ‘voracious’ predator of the freshwater snail, which is a carrier of schistosomiasis.

The researchers in Senegal said that, “market analysis in Senegal had shown there was significant interest among restaurant owners and farmers in introducing prawns to the diet.” The prawn could also for the basis of aquaculture in rice paddies and remove the threat of schistosomiasis from the rice workers.

—- Thank you for reading this week’s summary. These weekly abstractings have replaced our occasional mailings on tropical health issues due to fees introduced by those maintaining the listserve website. Also continue to check the Tropical Health Twitter feed, which you can see running on this page.

Borders &Diagnosis &Elimination &Environment &Gender &Health Education &Health Workers &Indoor Residual Spraying &IRS &ITNs &Mosquitoes &Plasmodium/Parasite &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 07 Jul 2019

The Weekly Tropical Health News 2019-07-06: Eliminating Malaria in Low Transmission Settings

This week started with articles that drew attention to the challenges of malaria in low transmission areas and with low density infections. Malaria Journal has provided several insightful articles toward this end.

Being an island has certainly helped Zanzibar make progress toward malaria elimination as witness the fact that malaria prevalence has remained below 1% for the past decade. Not only does Zanzibar still face threats of infection from the mainland, it may also experience an upsurge locally if residual transmission and the role of human behavior and community actions are not well understood. April Monroe et al. conducted in-depth interviews with community members and local leaders across six sites on Unguja, Zanzibar as well as semi-structured community observations of night-time activities and special events to learn more.

Being an island has certainly helped Zanzibar make progress toward malaria elimination as witness the fact that malaria prevalence has remained below 1% for the past decade. Not only does Zanzibar still face threats of infection from the mainland, it may also experience an upsurge locally if residual transmission and the role of human behavior and community actions are not well understood. April Monroe et al. conducted in-depth interviews with community members and local leaders across six sites on Unguja, Zanzibar as well as semi-structured community observations of night-time activities and special events to learn more.

While there was high reported ITN use, there were also times when people were exposed t mosquitoes while being outdoors during biting times. This could be around the house, or at special night events like such as weddings, funerals, and religious ceremonies. Men spent more time outdoors than women. Clearly appropriate interventions and needed and should be promoted in culturally appropriate ways in order to further reduce and eventually eliminate transmission.

Angela Early and colleagues presented findings on a diagnostic process of deep sequencing for understanding the dynamics and complexity of Plasmodium infections, but stress that knowing the lower limit of detection is challenging. They present “a new amplicon analysis tool, the Parallel Amplicon Sequencing Error Correction (PASEC) pipeline, is used to evaluate the performance of amplicon sequencing on low-density Plasmodium DNA samples.”

The authors learned that, “four state-of-the-art tools resolved known haplotype mixtures with similar sensitivity and precision.” They also cautioned that, “Samples with very low parasitemia and very low read count have higher false positive rates and call for read count thresholds that are higher than current default recommendations.” Better understanding of the genetic mix of plasmodium infections as countries move toward low transmission and elimination is crucial for selecting appropriate interventions and evaluating their outcomes.

Hannah Edwards and co-researchers examined conditions for malaria transmission along the Thailand-Myanmar border in areas approaching malaria elimination. While prevalence may be less than 1%, residual transmission still occurs. Transmission occurs not only around residences but in the forests where people work. The researchers therefore looked at the behavior of both humans and insects. Overall, they found that, “Community members frequently stayed overnight at subsistence farm huts or in the forest. Entomological collections showed higher biting rates of primary vectors in forested farm hut sites and in a more forested village setting compared to a village with clustered housing and better infrastructure.”

Hannah Edwards and co-researchers examined conditions for malaria transmission along the Thailand-Myanmar border in areas approaching malaria elimination. While prevalence may be less than 1%, residual transmission still occurs. Transmission occurs not only around residences but in the forests where people work. The researchers therefore looked at the behavior of both humans and insects. Overall, they found that, “Community members frequently stayed overnight at subsistence farm huts or in the forest. Entomological collections showed higher biting rates of primary vectors in forested farm hut sites and in a more forested village setting compared to a village with clustered housing and better infrastructure.”

While mosquitoes preferred to bite inside huts, their threat was magnified by those who did not use long lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs). While out in the farms and forests, people tended to wake early and increase their likelihood of being bitten. The authors discuss the challenges of dual residences in terms of LLIN ownership and even concerning the potential access to indoor residual spraying. The definition for universal net coverage needs to expand from one net per two people to include adequate nets wherever people are located.

The Amazonian area of Brazil is another area working toward malaria elimination, in particular, Plasmodium vivax. Felipe Leão Gomes Murta et al. also looked at the human side of the equation and identified misperceptions by both community members and health workers that could inhibit elimination efforts. They found, “many myths regarding malaria transmission and treatment that may hinder the sensitization of the population of this region in relation to the use of current control tools and elimination strategies, such as mass drug administration (MDA),” and LLINs.

The Amazonian area of Brazil is another area working toward malaria elimination, in particular, Plasmodium vivax. Felipe Leão Gomes Murta et al. also looked at the human side of the equation and identified misperceptions by both community members and health workers that could inhibit elimination efforts. They found, “many myths regarding malaria transmission and treatment that may hinder the sensitization of the population of this region in relation to the use of current control tools and elimination strategies, such as mass drug administration (MDA),” and LLINs.

Problematic perceptions included mention by both groups that the use of insecticide-treated nets, may cause skin irritations and allergies. Both community members and health professionals said malaria is “an impossible disease to eliminate because it is intrinsically associated with forest landscapes.” They concluded that such perceptions can be a barrier to control and elimination.

Efforts to eliminate malaria from low transmission settings are an essential to the overall global goals. These four articles tell us that close attention to and better understanding of humans, parasites and mosquitoes is still needed to achieve these goals.

Asymptomatic &Burden &Dengue &Diagnosis &Ebola &Elimination &Epidemiology &Health Systems &ITNs &MDA &Mosquitoes &NTDs &Schistosomiasis &Schools &Vector Control &Zoonoses Bill Brieger | 30 Jun 2019

The Weekly Tropical Health News 2019-06-29

Below we highlight some of the news we have shared on our Facebook Tropical Health Group page during the past week.

Polio Persists

If all it took to eradicate a disease was a well proven drug, vaccine or technology, we would not be still reporting on polio, measles and guinea worm, to name a few. In the past week Afghanistan reported 2 wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) cases, and Pakistan had 3 WPV1 cases. Circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) was reported in Nigeria (1), DRC (4) and Ethiopia (3) from healthy community contacts.

Continued Ebola Challenges

In the seven days from Saturday to Friday (June 28) there were 71 newly confirmed Ebola Cases and 56 deaths reported by the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Ministry of Health. As Ebola cases continue to pile up in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with 12 more confirmed Thursday and 7 more Friday, a USAID official said four major donors have jump-started a new strategic plan for coordinating response efforts. To underscore the heavy toll the outbreak has caused, among its 2,284 cases, as noted on the World Health Organization Ebola dashboard today, are 125 infected healthcare workers, including 2 new ones, DRC officials said.

Pacific Standard explained the differences in Ebola outbreaks between DRC today and the West Africa outbreak of 2014-16. On the positive side are new drugs used in organized trials for the current outbreak. The most important factor is safe, effective vaccine that has been tested in 2014-16, but is now a standard intervention in the DRC. While both Liberia and Sierra Leone had health systems and political weaknesses as post-conflict countries, DRC’s North Kivu and Ituri provinces are currently a war zone, effectively so for the past generation. Ebola treatment centers and response teams are being attacked. There are even cultural complications, a refusal to believe that Ebola exists. So even with widespread availability of improved technologies, teams may not be able to reach those in need.

To further complicate matters in the DRC, Doctors Without Borders (MSF) “highlighted ‘unprecedented’ multiple crises in the outbreak region in northeastern DRC. Ebola is coursing through a region that is also seeing the forced migration of thousands of people fleeing regional violence and is dealing with another epidemic. Moussa Ousman, MSF head of mission in the DRC, said, ‘This time we are seeing not only mass displacement due to violence but also a rapidly spreading measles outbreak and an Ebola epidemic that shows no signs of slowing down, all at the same time.’”

NIPAH and Bats

Like Ebola, NIPAH is zoonotic, and also involves bats, but the viruses differ. CDC explains that, “Nipah virus (NiV) is a member of the family Paramyxoviridae, genus Henipavirus. NiV was initially isolated and identified in 1999 during an outbreak of encephalitis and respiratory illness among pig farmers and people with close contact with pigs in Malaysia and Singapore. Its name originated from Sungai Nipah, a village in the Malaysian Peninsula where pig farmers became ill with encephalitis.

A recent human outbreak in southern India has been followed up with a study of local bats. In a report shared by ProMED, out of 36 Pteropus species bats tested for Nipah, 12 (33%) were found to be positive for anti-Nipah bat IgG antibodies. Unlike Ebola there are currently no experimental drugs or vaccines.

Climate Change and Dengue

Climate change is expected to heighten the threat of many neglected tropical diseases, especially arboviral infections. For example, the New York Times reports that increases in the geographical spread of dengue fever. Annually “there are 100 million cases of dengue infections severe enough to cause symptoms, which may include fever, debilitating joint pain and internal bleeding,” and an estimated 10,000 deaths. Dengue is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes that also spread Zika and chikungunya. A study, published Monday in the journal Nature Microbiology, found that in a warming world there is a strong likelihood for significant expansion of dengue in the southeastern United States, coastal areas of China and Japan, as well as to inland regions of Australia. “Globally, the study estimated that more than two billion additional people could be at risk for dengue in 2080 compared with 2015 under a warming scenario.”

Schistosomiasis – MDA Is Not Enough, and Neither Are Supplementary Interventions

Schistosomiasis is one of the five neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) that are being controlled and potentially eliminated through mass drug administration (MDA) of preventive chemotherapy (PCT), in this case praziquantel. In The Lancet Knopp et al. reported that biannual MDA substantially reduced Schistosomiasis haematobium prevalence and infection intensity but was insufficient to interrupt transmission in Zanzibar. In addition, neither supplementary snail control or behaviour change activities did not significantly boost the effect of MDA. Most MDA programs focus on school aged children, and so other groups in the community who have regular water contact would not be reached. Water and sanitation activities also have limitations. This raises the question about whether control is acceptable for public health, or if there needs to be a broader intervention to reach elimination?

Trachoma on the Way to Elimination

Speaking of elimination, WHO has announced major “sustained progress” on trachoma efforts. “The number of people at risk of trachoma – the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness – has fallen from 1.5 billion in 2002 to just over 142 million in 2019, a reduction of 91%.” Trachoma is another NTD that uses the MDA strategy.

The news about NTDs from Dengue to Schistosomiasis to Trachoma is complicated and demonstrates that putting diseases together in a category does not result in an easy choice of strategies. Do we control or eliminate or simply manage illness? Can our health systems handle the needs for disease elimination? Is the public ready to get on board?

Malaria Updates

And concerning being complicated, malaria this week again shows many facets of challenges ranging from how to recognize and deal with asymptomatic infection to preventing reintroduction of the disease once elimination has been achieved. Several reports this week showed the particular needs for malaria intervention ranging from high burden areas to low transmission verging on elimination to preventing re-introduction in areas declared free from the disease.

In South West, Nigeria Dokunmu et al. studied 535 individuals aged from 6 months were screened during the epidemiological survey evaluating asymptomatic transmission. Parasite prevalence was determined by histidine-rich protein II rapid detection kit (RDT) in healthy individuals. They found that, “malaria parasites were detected by RDT in 204 (38.1%) individuals. Asymptomatic infection was detected in 117 (57.3%) and symptomatic malaria confirmed in 87 individuals (42.6%).

Overall, detectable malaria by RDT was significantly higher in individuals with symptoms (87 of 197/44.2%), than asymptomatic persons (117 of 338/34.6%)., p = 0.02. In a sub-set of 75 isolates, 18(24%) and 14 (18.6%) individuals had Pfmdr1 86Y and 1246Y mutations. Presence of mutations on Pfmdr1 did not differ by group. It would be useful for future study to look at the effect of interventions such as bednet coverage. While Southwest Nigeria is a high burden area, the problem of asymptomatic malaria will become an even bigger challenge as prevalence reduces and elimination is in sight.

Sri Lanka provides a completely different challenge from high burden areas. There has been no local transmission of malaria in Sri Lanka for 6 years following elimination of the disease in 2012. Karunasena et al. report the first case of introduced vivax malaria in the country by diagnosing malaria based on microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests. “The imported vivax malaria case was detected in a foreign migrant followed by a Plasmodium vivax infection in a Sri Lankan national who visited the residence of the former. The link between the two cases was established by tracing the occurrence of events and by demonstrating genetic identity between the parasite isolates. Effective surveillance was conducted, and a prompt response was mounted by the Anti Malaria Campaign. No further transmission occurred as a result.”

Bangladesh has few but focused areas of malaria transmission and hopes to achieve elimination of local transmission by 2030. A particular group for targeting interventions is the population of slash and burn cultivators in the Rangamati District. Respondents in this area had general knowledge about malaria transmission and modes of prevention and treatment was good according to Saha and the other authors. “However, there were some gaps regarding knowledge about specific aspects of malaria transmission and in particular about the increased risk associated with their occupation. Despite a much-reduced incidence of malaria in the study area, the respondents perceived the disease as life-threatening and knew that it needs rapid attention from a health worker. Moreover, the specific services offered by the local community health workers for malaria diagnosis and treatment were highly appreciated. Finally, the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITN) was considered as important and this intervention was uniformly stated as the main malaria prevention method.”

Kenya offers some lessons about low transmission areas but also areas where transmission may increase due to climate change. A matched case–control study undertaken in the Western Kenya highlands. Essendi et al. recruited clinical malaria cases from health facilities and matched to asymptomatic individuals from the community who served as controls in order to identify epidemiological risk factors for clinical malaria infection in the highlands of Western Kenya.

“A greater percentage of people in the control group without malaria (64.6%) used insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) compared to the families of malaria cases (48.3%). Low income was the most important factor associated with higher malaria infections (adj. OR 4.70). Houses with open eaves was an important malaria risk factor (adj OR 1.72).” Other socio-demographic factors were examined. The authors stress the need to use local malaria epidemiology to more effectively targeted use of malaria control measures.

The key lesson arising from the forgoing studies and news is that disease control needs strong global partnerships but also local community investment and adaptation of strategies to community characteristics and culture.

Mosquitoes &Uncategorized &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 19 May 2019

Malaria – an old disease attacking the young population of Kenya

Wambui Waruingi recently described her experiences working on malaria in Kenya on the site, “Social, Cultural & Behavioral Issues in PHC & Global Health.” Her thoughts and lessons are found below.

Malaria is an old disease, and not unfamiliar to the people of Lwala, Migori county, Nyanza province, situated in Kenya, East Africa. The most vulnerable are pregnant women and young children.The Lwala Community Alliance have reduced the rate of under 5 mortality to 20% of what it was 10 years ago, and about 30% of what it is in Migori county (reported 29 deaths/ 1000 in 2018) https://lwala.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Lwala-2018-Annual-Report.pdf

Of the scourges that remain, malaria is one of them.

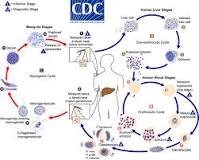

Malaria is caused by a protozoal species called Plasmodium spp; the most severe is Plasmodium falciparum, the predominant type in the region.It’s life cycle exemplifies evolution at it’s most sophisticated, albeit vulnerable, needing two hosts of different species to complete it’s life cycle, the mosquito, and mammalian species in stages of asexual then asexual reproduction respectively. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/malaria/symptoms-causes/syc-20351184https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/biology/index.html

The mosquito types responsible for malaria in the area are A. gambiae spp and A. arabiensis spp. To complete it’s life cycle, the mosquito requires water, or an aquatic environment to develop it’s larvae. This insect therefore seeks to lay it’s eggs in pools of fresh water, abundant in the area due to Lake Victoria, and important source of the local staple fish, and areas of underdeveloped grassland surrounding the lake and village. https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1475-2875-9-62

WHO reported 219 million cases of malaria world wide, with 435,000 deaths in the same year. In this day and age, malaria remains burdensome in 11 countries, 10 of them being in Africa. WHO recommends a focused response. https:// who.int/malaria/en/. I advocate a focus on prevention by eradicating mosquitoes and episodes of mosquito bites in the region. WHO vector control guidelines run along the idea of chemical and biological larvicides, topical repellents,and personal protective measures, such as bed nets, wearing long sleeves and pants (hard to do in the heat of Migori), bug spray and insecticide treated nets. These are effective.

In the area, mosquitoes capitalize on both daytime and nighttime feeding. Lwala benefits from a mosquito net distribution program so there is at least 1 net/ per household and a coverage of about 95%, https://lwala.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Lwala-2018-Annual-Report.pdf, but there is an average of 5.5 individuals per household,

file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Migori%20County.pdf , so it conceivable that not all children under 5 currently sleep under a net.

Let’s start by making sure they do by scaling up this program, so that the number of nets corresponds with the number of individuals per household.

Lwala is an active community, and while use of nets will eliminate night feeders such as A. gambiae , little children will be susceptible to mosquito bites given that they are outdoors nearly daily helping with activities such as fishing, goat herding, fetching water and so forth. That is why active programs for mosquito eradication make so much sense in the region. While promoting personal prevention measures such as the use of “bugspray” containing effective substances such as DEET, efforts by the Bill and Melissa gates foundation, through the Malaria R&D (research and development) active since 2004, have devoted over $323 million dollars, about 20% ($50.4 million) of which has gone to the Innovative Vector Control Consortium, (IVCC) led by the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The aim is to fast track improved insecticides, both biological and chemical, and other measures of vector control. I suggest that partnership with the IVCC be scaled up in the area, allowing Lwala to be first line in any benefits thereof. https://www.gatesfoundation.org/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2010/11/IVCC-Develops-New-Public-Health-Insecticides, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/Media-Center/Press-Releases/2005/10/Gates-Foundation-Commits-2583-Million-for-Malaria-Research

Finally, it’s official. Research endorses use of nets and indoor residual spraying as an effective way to reduce malaria density. https://malariajournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12936-016-1214-9. This should be coupled with house improvement, since much of traditional and poverty-maintained materials, allow environments in which the mosquito can hide, to come out later to feed, and even breed. In Migori county, 72% of the homes have earth floors, 76% have corrugated roofs, and 21% have grass-thatched roofs. file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Migori%20County.pdf

All these promote a healthy habitat for the mosquito during the rainy season, and easy entry and hiding places all year round. Funding to improve house types so that locally-sourced but sturdy, water-proof homes can be built, will eliminate opportunities for the mosquito to access and bite young children.

Let’s get stakeholders vested in this effective, yet economical way to address malaria deaths in the youngest children. Starting now, funding should be diverted from costly treatments with ever mounting resistance patterns, to causing extinction of the Anopheles mosquito in Migori county. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”http://drjarodhalldpt.blogspot.com/2018/02/an-ounce-of-prevention-is-worth-pound.html

Economics &ITNs &Mosquitoes &Vector Control Bill Brieger | 25 Oct 2017

Mis-Use of Insecticide Treated Nets May Actually Be Rational

People have sometimes question whether insecticide treated nets (ITNs) provided for free are valued by the recipients. Although this is not usually a specific question in surveys, researchers found in a review of 14 national household surveys that free nets received through a campaign were six times more likely to be given away than nets obtained through other avenues such as routine health care or purchased from shops.

Giving nets away to other potential users, not hanging nets or not sleeping under nets at least imply that the nets could potentially be used for their intended purpose. What concerns many is that nets may be used for unintended and inappropriate reasons. Often the evidence is anecdotal, but photos from Nigeria and Burkina Faso shown here document cases where nets were found to cover kiosks, make football goalposts, protect vegetable seedlings and fence in livestock.

Giving nets away to other potential users, not hanging nets or not sleeping under nets at least imply that the nets could potentially be used for their intended purpose. What concerns many is that nets may be used for unintended and inappropriate reasons. Often the evidence is anecdotal, but photos from Nigeria and Burkina Faso shown here document cases where nets were found to cover kiosks, make football goalposts, protect vegetable seedlings and fence in livestock.

Newspapers tend to quote horrified health or academic staff when reporting this, such as this statement from Mozambique, “The nets go straight out of the bag into the sea.” The Times said that net misuse squandered money and lives when they observed that “Malaria nets distributed by the Global Fund have ended up being used for fishing, protecting livestock and to make wedding dresses.”

Two years ago the New York Times reported that, “Across Africa, from the mud flats of Nigeria to the coral reefs off Mozambique, mosquito-net fishing is a growing problem, an unintended consequence of one of the biggest and most celebrated public health campaigns in recent years.”5 Not only were people not being protected from malaria, but the pesticide in these ‘fishing nets’ was causing environmental damage. The article explains that the problem of such misuse may be small, but that survey respondents are very unlikely to admit to alternative uses to interviewers.

Two years ago the New York Times reported that, “Across Africa, from the mud flats of Nigeria to the coral reefs off Mozambique, mosquito-net fishing is a growing problem, an unintended consequence of one of the biggest and most celebrated public health campaigns in recent years.”5 Not only were people not being protected from malaria, but the pesticide in these ‘fishing nets’ was causing environmental damage. The article explains that the problem of such misuse may be small, but that survey respondents are very unlikely to admit to alternative uses to interviewers.

Similarly El Pais website featured an article on malaria in Angola this year with a striking lead photo of children fishing in the marshes near their village in Cubal with a LLIN. A video from the New York Times frames this problem in a stark choice: sleep under the nets to prevent malaria or them it to catch fish and prevent starvation.[v]

More recently, researchers who examined net use data from Kenya and Vanuatu found that alternative LLIN use is likely to emerge in impoverished populations where these practices had economic benefits like alternative ITN uses sewing bednets together to create larger fishing nets, drying fish on nets spread along the beach, seedling crop protection, and granary protection. The authors raise the question whether such uses are in fact rational from the perspective of poor people.

More recently, researchers who examined net use data from Kenya and Vanuatu found that alternative LLIN use is likely to emerge in impoverished populations where these practices had economic benefits like alternative ITN uses sewing bednets together to create larger fishing nets, drying fish on nets spread along the beach, seedling crop protection, and granary protection. The authors raise the question whether such uses are in fact rational from the perspective of poor people.

An important fact is that not all ovserved ‘mis-use’ of nets is really inappropriate use. A qualitative study in the Kilifi area of coastal Kenya demonstrated local ‘recycling’ of old ineffective nets. The researchers clearly found that in rural, peri-urban and urban settings people adopted innovative and beneficial ways of re-using old, expired nets, and those that were damaged beyond repair. Fencing for livestock, seedlings and crops were the most common uses in this predominantly agricultural area. Other domestic uses were well/water container covers, window screens, and braiding into rope that could be used for making chairs, beds and clotheslines. Recreational uses such as making footballs, football goals and children’s swings were reported

What we have learned here is that we should not jump to conclusions when we observe a LLIN that is set up for another purpose than protecting people from mosquito bites. Alternative uses of newly acquired nets do occur and may seem economically rational to poor communities. At the same time we must ensure that mass campaigns pay more attention to community involvement, culturally appropriate health education and onsite follow-up, especially the involvement of community health workers. Until such time as feasible safe disposal of ‘retired’ nets can be established, it would be good to work with communities to help them repurpose those nets that no longer can protect people from malaria.

Climate &Community &Development &Epidemiology &Malaria in Pregnancy &Mosquitoes &Surveillance &Urban &Zoonoses Bill Brieger | 11 Jul 2017

Population Health: Malaria, Monkeys and Mosquitoes

On World Population Day (July 11) one often thinks of family planning. A wider view was proposed by resolution 45/216 of December 1990, of the United Nations General Assembly which encouraged observance of “World Population Day to enhance awareness of population issues, including their relations to the environment and development.”

On World Population Day (July 11) one often thinks of family planning. A wider view was proposed by resolution 45/216 of December 1990, of the United Nations General Assembly which encouraged observance of “World Population Day to enhance awareness of population issues, including their relations to the environment and development.”

A relationship still exists between family planning and malaria via preventing pregnancies in malaria endemic areas where the disease leads to anemia, death, low birth weight and stillbirth. Other population issues such as migration/mobility, border movement, and conflict/displacement influence exposure of populations to malaria, NTDs and their risks. Environmental concerns such as land/forest degradation, occupational exposure, population expansion (even into areas where populations of monkeys, bats or other sources of zoonotic disease transmission live), and climate warming in areas without prior malaria transmission expose more populati ons to mosquitoes and malaria.

ons to mosquitoes and malaria.

Ultimately the goal of eliminating malaria needs a population based focus. The recent WHO malaria elimination strategic guidance encourages examination of factors in defined population units that influence transmission or control.

Today public health advocates are using the term population health more. The University of Wisconsin Department of Population Health Sciences in its blog explained that “Population health is defined as the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group.” World Population Day is a good time to consider how the transmission or prevention of malaria, or even neglected tropical diseases, is distributed in our countries, and which groups and communities within that population are most vulnerable.

World Population Day has room to consider many issues related to the health of populations whether it be reproductive health, communicable diseases or chronic diseases as well as the services to address these concerns.