Human Resources &Research Bill Brieger | 11 Oct 2013

Looking toward Generation F3 and Beyond – Sustaining Malaria Research Capacity in Africa

Olumide Ogundahunsi, of WHO/TDR Geneva, Switzerland provided a look back and toward the future of the Multilateral Initiative for Malaria (MIM) during one of the final plenary sessions at the MIM2013 6th Pan-African Malaria Conference in Durban. Excerpts from his talk and slides are presented below…

Twenty years ago, we were asleep, malaria elimination was a dream, and the reality was a nightmare. After the serial failures of the malaria eradication campaign in Africa, malaria control was barely moving along. But today we are wide awake, it is not yet “uhuru” as far as malaria goes but we are making gains having learnt the importance of combined interventions, we are applying them with success in a number of places.

Twenty years ago, we were asleep, malaria elimination was a dream, and the reality was a nightmare. After the serial failures of the malaria eradication campaign in Africa, malaria control was barely moving along. But today we are wide awake, it is not yet “uhuru” as far as malaria goes but we are making gains having learnt the importance of combined interventions, we are applying them with success in a number of places.

However, there is still some distance to go in this war and many battles ahead. To quote one of the plenary speakers during this conference, “the fight against malaria can only be won by well-trained people” (Dr Robert Newman). …..

- People who have the necessary capacity to optimise the available tools and develop new ones.

- People who are embedded in the endemic countries

- People who know and understand the contexts in which the tools and interventions will be deployed.

- Communities empowered to implement and sustain interventions

The issue I would like to ponder in the next half hour is how we ensure that we have enough of these people to do the job!

The last time we were in Durban (as the MIM), the Welcome Trust, the MIM secretariat at that time, had just published a comprehensive report on malaria research capacity in Africa. The report included data on for example the number of African institutions publishing more than 10 malaria related papers in the 3 years preceding the report – a mere 15 in the whole continent! This has changed significantly in the past 14 years to 38 Institutions.

The last time we were in Durban (as the MIM), the Welcome Trust, the MIM secretariat at that time, had just published a comprehensive report on malaria research capacity in Africa. The report included data on for example the number of African institutions publishing more than 10 malaria related papers in the 3 years preceding the report – a mere 15 in the whole continent! This has changed significantly in the past 14 years to 38 Institutions.

Fifteen years ago only a handful of agencies and programs were interested in research capacity strengthening and there were even those who considered capacity building poor investments…..the situation has of course changed since and the members of my generation – the so called F2 generation who were either graduate students or post docs at that time maturing as

- Established researchers in reputable and highly successful institutions

- Working in Africa and meeting the challenges of working in a challenging environment

- Highly motivated scientists recognised by their peers and the international scientific community

- Contributing to research and control of malaria in their countries and the continent

Of the 90 plus researchers in the F2 generation only 4 are no longer working in Africa. They remain committed and well recognized experts in their fields.

There are also several institutions that have evolved in the past 14 years because of support for RCS…. Noguchi Memorial Institute or medical research in Ghana and the health research facilities in Kitampo, Bagamoyo, Centre Muraz Bobo Diolasso and the Centre Nationale de Recherche et de Formation Paludisme (CNRFP) in Ouagadougou. CNRFP received the first grant in 1999 (slide 11) to study the relationship between malaria transmission intensity and clinical malaria, immune response and plasmodic index. The institution has since grown from a modest staff of six in 1999 to 36 currently.

There are also several institutions that have evolved in the past 14 years because of support for RCS…. Noguchi Memorial Institute or medical research in Ghana and the health research facilities in Kitampo, Bagamoyo, Centre Muraz Bobo Diolasso and the Centre Nationale de Recherche et de Formation Paludisme (CNRFP) in Ouagadougou. CNRFP received the first grant in 1999 (slide 11) to study the relationship between malaria transmission intensity and clinical malaria, immune response and plasmodic index. The institution has since grown from a modest staff of six in 1999 to 36 currently.

It has acquired well established capacities for operational / implementation research, clinical trials and studies on vector management (slide 113, and funding from several international partners.

These stories illustrate how capacity is being built in Africa not only by WHO/TDR and the MIM but also MCDC, the WT, EDCTP/EC, the NIH, BMGF and SIDA/SAREC among others.

Is this enough? And can we rest content on the success and contributions of the current generation of African malaria researchers? Is the capacity adequate?

It will be naive to look at Africa as a single entity as is often done. The capacity (human resource and infrastructure) for research and control against malaria does not match the burden or the scope of the battle. There are still places where there are:

- Limited human resources

- Lack of infrastructure

- Funding disparity

- Limited access to technology

- Limited interactions between the research and control communities

The last of these….. “limited interactions between research and control communities“ in particular pose a significant barrier to effective deployment of interventions and strategies.

The last of these….. “limited interactions between research and control communities“ in particular pose a significant barrier to effective deployment of interventions and strategies.

It is not enough to prove that a strategy or an intervention works (often in a controlled setting). In the real life context, there are multiple factors ranging from the quality and structure of the health system, to culture, the political, and the socio economic that impact on our ability to effectively implement or scale up for impact.

The next generation of malaria researchers in Africa must be able to better address this gap if we must extend the frontiers of malaria elimination and shrink the malaria map further.

I can say most of the current generation (my generation) stood on the shoulders of an older generation of African scientists and their collaborators in other continents (someone referred to them as baobab trees a few days ago), the exposure, training, mentorship and the opportunities they created following Dakar have helped us along……

However when you consider the proportion of Africans speaking at the plenaries during this conference and the number of young scientists and graduate students attending as a whole, I think we have still have a long way to go!

How can we foster the next generation and further strengthen capacity for malaria research in Africa – within the unique context of each country.

As I conclude I want to reflect on the African perspective of training needs and solutions. 14 years ago in identifying enhancers of developing and maintaining a research career in tropical medicine in Africa, we put forward the following:

- Research funding

- Research infrastructure

- Communications

- Better salaries and career development

- High quality training

To this I could add one more …. Mentoring

These issues remain highly relevant and must be continuously addressed if we are to sustain and indeed improve malaria research capacity in Africa.

These issues remain highly relevant and must be continuously addressed if we are to sustain and indeed improve malaria research capacity in Africa.

Since the creation of MIM, we have seen an increase in research funding in Africa, emergence of centers of excellence, better communication and collaboration to a large extent driven by the global it boom. Better salaries, career development and high quality training!

However in general, funding for research including operations research (and capacity building) in Africa is to a large extent dependent on external funding.

National efforts at capacity building are to a large extent limited to statutory funding for graduate, postgraduate and diploma programmes. Beyond this there is little funding for post-doctoral research training, operational research within programs or innovative product research and development.

In the more than almost one and a half decade since the global community committed to Roll Back Malaria, we have had malaria initiatives from presidents but the human resources to under pin these efforts remain inadequate. We have to do better in capacity building so that 10 years down the road, there is a new generation of well-trained people embedded in the endemic countries with the capacity to optimise the tools and develop new ones if necessary. Now is the time ……….

- To lobby and convince African political leaders and governments to invest in research and capacity building

- To convince the African billionaires who feature in Forbes list to invest in African scientists

- And to the senior, successful and established African scientists and managers…. It is time to invest in younger talent as mentors.

In 1997, MIM was in the vanguard of an effort to address the issues of

- Research funding

- Research infrastructure

- Communications

- Better salaries and career development

- High quality training

Bringing these issues to the attention of the international community and in some cases providing inputs to address them is still an important part of the MIM agenda.

The MIM is even more important now as an advocate for research and capacity building in Africa. WHO/TDR will work with the MIM secretariat to conduct an independent review of the MIM for continued relevance and contribution to the fight against malaria.

Human Resources Bill Brieger | 09 Oct 2013

Where are human resource capacity issues addressed at MIM2013

MIM2013 is at its half-way mark. Ironically the issue of the number, the quality and the location of human resource capacity for malaria programming has not been explicitly addressed in the program.

Sure, individual speakers had talked a bit about personnel needed for vector control, community case management, diagnostics, among others, but few specific session – symposium, plenary or parallel paper presentations- were titled in a way that focused conclusively about the people who are needed to achieve these program tasks and goals. There were even two parallel sessions on health systems strengthening, but these addressed such topics as changing prescribing practices, vaccines and treatment seeking.

One looked forward to human resource issues being raised in a session that addressed task shifting in malaria prescribing and in capacity for designing clinical trials for vaccines. This was overwhelmed by the plethora of presentations on vector issues that did not include a specific presentation on adequacy and skills of entomologists in endemic countries.

Fifteen years ago the Roll Back Malaria partnership recognized that malaria targets could not b achieved unless malaria programming went hand-in-hand with health systems strengthening. Malaria services were seen as an integral part of basic primary health care and the people, staff and volunteers who provided PHC.

Conference speakers recognize the financial and logistical factors that make coverage, let alone achieving a complete cure and complete prevention as described by Dr Magill challenging. Yet this is not enough. Who are the people who will provide these complete interventions, how will they be trained, and where will they be posted?

One MIM conference participant observed that conference panels were dominated by too many older, non-African scientists. This reflects either an oversight by conference planners of the reality that we lack enough African health and research personnel to take the lead in eliminating malaria. We are particularly concerned for the special people and skills needed to apply appropriate surveillance and lead us to malaria elimination.

It will be too late to address these human resources issues by the next MIM conference. Hopefully in the meantime countries will plug into the ongoing moves to strengthen human resources for health and ensure that they have enough well trained people to diagnose disease, manage cases, prevent transmission and track malaria, This needs to be addressed through both in-service and basic pre-service training programs.

Human Resources &MIM2013 Bill Brieger | 29 Sep 2013

Human Resources for Malaria

Two major international meetings are coming up in the next two months. One if the Multilateral Initiative for Malaria’s 6th Pan-African Malaria Conference (MIM2013) and the Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health. Neither apparently cross-reference the other. None of the Plenary Sessions or Symposiums at MIM2013 explicitly address the crucial need of appropriate human resources to eliminate malaria, though we are sure it will be woven in to several presentations.

One of the most prominent focal points for malaria human resources arises from the effort to expand integrated Community Case Management (iCCM). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene features a special supplement launched at its 2012 annual Conference on iCCM. The most interesting aspect of the iCCM movement is the innovative task shifting that is occurring to bring malaria and other disease solutions to the grassroots through a variety of auxiliary health workers and community volunteers. It has become clear that malaria treatment coverage cannot meet targets – either the 2010 Roll Back Malaria goal or 80%, let alone the push toward universal coverage – without involving non-formal providers such as volunteer community health workers (CHWs) as well as patent medicine shop staff.

One of the most prominent focal points for malaria human resources arises from the effort to expand integrated Community Case Management (iCCM). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene features a special supplement launched at its 2012 annual Conference on iCCM. The most interesting aspect of the iCCM movement is the innovative task shifting that is occurring to bring malaria and other disease solutions to the grassroots through a variety of auxiliary health workers and community volunteers. It has become clear that malaria treatment coverage cannot meet targets – either the 2010 Roll Back Malaria goal or 80%, let alone the push toward universal coverage – without involving non-formal providers such as volunteer community health workers (CHWs) as well as patent medicine shop staff.

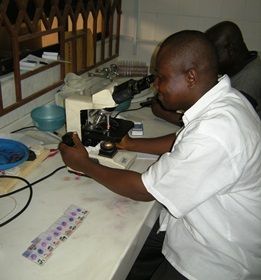

But finding human resources for treatment tasks is only the tip of the iceberg. A variety of health workers are needed for malaria work in the areas of entomology/vector control, health information systems/surveillance, and laboratory/diagnosis, to name three.

The Global Health Workforce Alliance did issue a report in 2011 that questioned the ability of countries to meet Millennium Development Goal number 6 – reducing the inpact of HIV, TB, Malaria and other endemic diseases. Issues such as the distribution of health workers in a country were raised – especially the challenge of meeting the needs of rural areas where malaria is more common.

Training has a major role to play. When Jhpiego/MCHIP began a 3-year effort with USAID to improve malaria services in Burkina Faso in 2009, they found a need to provide in-service training on malaria for newly graduated nurses and midwives. An examination of the curricula of the various cadres and branches of the National School for Public Health (ENSP) found a paucity of malaria content, especially content that reflected current national malaria guidelines from the Ministry of Health. This led to work with the ENSP to set up a planning committee to update the malaria components of its curricula.

WHO has a variety of training materials on issues and cadres ranging from strengthening malaria laboratory workers, entomology and vector control staff, as well as the basic training of health workers involved in malaria case management.

WHO has a variety of training materials on issues and cadres ranging from strengthening malaria laboratory workers, entomology and vector control staff, as well as the basic training of health workers involved in malaria case management.

In addition to issues of health worker number are the issues of retention and performance quality. Researchers in Kenya are undertaking a study that will test whether a pay-for-performance (P4P) will improve malaria case management. Pay incentives might aid retention as well as improve quality of care. We need more such efforts to tackle the coverage gaps in malaria service delivery. This also means addressing the human resource gaps among malaria researchers in national institutes and universities in endemic countries.

We need to use every forum available to discuss human resources for malaria control, elimination and eradication. The scourge of malaria will linger as long as we lack the quantity and quality of human resources to fight the disease.

Human Resources &Malaria in Pregnancy &Mortality Bill Brieger | 02 Dec 2010

Nigeria Midwives Scheme May Help Control Malaria

Nigeria has introduced the Midwives Service Scheme (MSS) through its National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) to meet the needs of women and children served by basic primary health care clinics rural communities. There is hope that the scheme will help to address the country’s high maternal mortality rate, which according to the 2008 Demographic and Health Survey, averages 545/100,000 live births, but ranges widely across the country’s six health zones from 165 to 1549.

Nigeria used to have separate midwife and nurse training, but some years ago midwifery became a specialty area for nursing training, not a stand alone profession. Fortunately the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria maintained its name and is now an active player along with the NPHCDA and the Society of Gyneacology and Obstetrics of Nigeria (SOGON) in reintroducing and strengthening the training of midwives.

Nigeria used to have separate midwife and nurse training, but some years ago midwifery became a specialty area for nursing training, not a stand alone profession. Fortunately the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria maintained its name and is now an active player along with the NPHCDA and the Society of Gyneacology and Obstetrics of Nigeria (SOGON) in reintroducing and strengthening the training of midwives.

The first batch of the new midwives graduated in 2006. The intention is that up to four midwives will serve a basic primary health clinic (PHC) enabling 24-hour delivery services.

The NPHCDA conducted a baseline survey recently in 652 PHCs throughout the country where the midwives are or would be serving. Of interest to malaria control, the study reported that 73% of these facilities offered Intermittent Preventive Treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine to pregnant women, and only 48% provided insecticide treated bednets.

Providing a cadre of health workers focused women and children is an important step in malaria control. Ensuring that these staff have the resources to prevent malaria during and after pregnancy must be part of the total package.

Health Systems &Human Resources &Migration Bill Brieger | 19 Dec 2009

Health worker migration – push or pull?

The New Vision of Uganda reports that according to the 2009 Human Development Report, “THE majority of Ugandans who migrate to other countries are among the higher educated group. And those who migrate, whether within their own country or abroad, are doing better in terms of income, education and health than those who stayed where they were born.”

Health workers are among those educated emigrants, but the factors behind their movement are complex.

Citing the case of health workers deserting Africa, (the World Development Report) explains that this is being caused by poor staffing levels and poor public health conditions. “Migration is more accurately portrayed as a symptom, not a cause, of failing health systems.â€Â It notes that improving working conditions at home might be a better strategy to stop the brain-drain than restricting emigration.

The Canadian Medical Association Journal explains the problem thus:

You can’t force someone to stay and attempt to work in a place that is lacking even minimum provisions for them to do their job. “If you tell them they can only hand out band-aids and aspirin, no one will stay,” says Dr. Otmar Kloiber, secretary general of the World Medical Association. “People should have the privilege to migrate. For medical workers it’s important to have exchanges in order to learn and to work. You can’t put someone on a dead end road and ask them to build a health care system.”

WHO also reminds us that health workforce maldistribution and migration occurs within countries, too. “Approximately one half of the global population lives in rural areas, but these people are served by only 38% of the total nursing workforce and by less than a quarter of the total physicians’ workforce.” Health workers locate in urban centers to gain greater economic, educational and social opportunities for themselves and their families.”

The loss of health workers is a major impediment in implementing malaria coverage targets and making progress toward disease elimination even when malaria commodities are provided in adequate amounts. More generally, WHO notes that, “Without available, competent, and motivated health workers, the potential for achieving the Millennium Development Goals, and for effective, efficient use of the financial and other resources committed to achieving the Goals, remains extremely limited.”

The solution, according to the comments above is not simply finding more people to deliver malaria services in isolation, but ensuring that malaria control services are integrated into a well functioning health system. Donors who provide malaria and other health and development support are also cautioned to become aware of how their own programs, policies and activities can disrupt the health workforce in the countries receiving aid.

Health Systems &Human Resources Bill Brieger | 27 Sep 2009

When health workers strike

There are often opposing views about whether health workers should be able to strike or should be considered essential service staff who must remain on the job and resolve labor issues through other means. It should be noted that when most people talk about health workers striking, they are talking almost exclusively about health staff in the public sector, which in many malaria endemic is the largest provider of care, especially preventive services.

IRIN News reports today on a health worker strike in Adamawa State, Nigeria that has paralyzed service delivery. In-patients in government facilities have been discharged, and a very rudimentary out-patient service has been maintained. The strike is now in its third month, and as IRIN reports

Most of the state’s 7,000 health workers, including nurses, specialists and administrators but not general doctors, began an indefinite strike on 25 June to protest the suspension of an improved salary structure by the state government, according to head of the health workers union.

Although private care is available, “Only a few patients who can afford high medical fees have moved to private clinics, while [most] have resigned to their homes hoping the matter is soon resolved and the strike suspended.” Of special concern is the inability of the state to respond to an impending cholera epidemic.

In Gabon earlier this year a 3-month strike “demanding premiums, pay raises and better work facilities” was reported to have cost many lives. One man told IRIN that, “He is at a loss as to what to do about his three-year-old daughter who he said has had a severe cough for two weeks. ‘I do not have the means to take her to a private hospital. My only recourse is the [public hospital], so I just do not know what to do and this saddens me deeply.'”

In Cote d’Ivoire back in February, “After talks between the medical workers’ union and the government broke down … union leaders called a strike … Unlike past strikes medical workers are maintaining minimum services – emergency care, similar to that normally provided on weekends and holidays, said the union leader.”

The relationship between health workers and government often appears contentious. As one physician told IRIN, “We do not like going on strike. We know that people are in hard times, given the situation of the country. But we have been forced to do so.” Obviously the government cannot ‘force’ people to strike, but what does this say about the overall management and priority of health in a heavily government dependent setting?

These health systems and management issues were cause for reflection by Afrol News. Health workforce problems have “been a recurring matter in most part of Ghana’s 50-year existence, especially as economic conditions worsen. While public health workers deserve good pay, like other professionals, their problems are increasingly being worsened by mounting health problems and population increases. This calls for sober and holistic reflection of the entire Ghanaian healthcare delivery system.”

Part of the problem may increased pressure on existing staff because of workforce shortages. “Sub-Sahara Africa alone needs about 1 million health workers,” reports Afrol News. This may reflect a vicious cycle of disappointed staff, brain drain, greater staff shortages and even more disgruntled and overworked staff.

A basic principle in human resources management is that self-actualization at the worksite – being able to perform one’s duties with all the necessary resources – is more satisfying and motivating than salary, which can never be seen as enough. Since malaria control services need to be well integrated into primary care, we need to ask whether donor programs are adequately addressing issues like skill upgrading, quality control, timely and adequate procurement and supply, and other basic health service components that will make it possible for health workers to perform their duties and gain maximum job satisfaction.

We may think we are doing enough in providing billions of dollars of malaria commodities to endemic countries, but unless we address these human resource concerns, strikes may render these malaria control services unavailable just when people need them.

Human Resources &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 21 May 2009

Malaria Training Trounced by Transfers

In an effort to ensure the human capacity to deliver malaria services, partners are embarking on in-service and pre-service training throughout endemic countries. Such training is not something that can be accomplished quickly. Most partners plan training in a phased approach that eventually covers all districts and facilities, but quality training cannot be rushed.

Jhpiego has a 35 year history of capacity building of the health workforce in maternal and reproductive health, including the issue of malaria in pregnancy. Jhpiego has been working in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria for the past 2 years to test the concept of community-clinic collaboration in the delivery of malaria in pregnancy control services. The effort began by developing a core team of trainers at the state level, who in turn trained another core among staff of seven of the states 31 local government areas (LGA).

These LGA teams then embarked on training front line health facility staff in both malaria in pregnancy control and outreach through community directed interventions. The actual service delivery of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) took off in July 2008 after both health workers and community selected and directed volunteers were trained. Nearly 10,000 pregnant women have received two doses of IPTp since then.

Now the Pioneer Newspaper reports that many of those trained have been transferred to other LGAs, and this could disrupt the smooth delivery of MIP control services. The challenge in Nigeria is that while the State Ministry of Health provides technical guidance to LGA health staff, and the LGA itself provides the facilities and supplies to run the services, most of the actual health workers are employed by another entity – the State Local Government Service Commission. Transfers and repostings occur as frequently as every two years or only as often as every 5 years. Often a transfer is the only way a health worker can move into a higher grade position – in effect get a promotion.

So while the system may benefit the individual employee, it makes it difficult to offer continuity in service and to build strong community relations needed to deliver public health care. Eventually the State will have the resources through the World Bank Malaria Booster Program to train health staff in all LGAs on malaria. In the short term the efforts to prove that LGA health facilities can improve the quality and reach of malaria in pregnancy control services may be jeopardized.

The ultimate irony is that the bulk of health workers on the front line in Nigeria are not part of a system that could provide coordinated human resource planning for health. Instead, they are transfered by a non-health bureaucracy like any other LGA civil servant, whether she be a clerk, accountant, secretary or in this case a nurse. When Nigerian health planners are able to train and update all health staff in malaria, such transfers may not disrupt services. For now, these planners need to examine the effects of a system that treats health staff like civil service pawns.

Health Systems &Human Resources Bill Brieger | 10 Dec 2008

Training – as important as commodities

New tools are said to be the answer to the question of malaria eradication. Even with the not so new tools available – ACTs, RDTs, IRS, LLINs, IPTp, IPTi – progress toward elimination can be made if health workers are trained in their appropriate use. Ssekabira and colleagues found that training improved some aspects of malaria case management such as reduced treatment of people testing negative in the lab, but they also pointed out that there needs to be integrated ‘team based’ training around all these tools in order to achieve success.

In their focus on training for improved malaria case management SSekabira’s group learned that ‘integrated’ means getting all clinical and laboratory staff on board as well as ensuring adequate procurement/supply of drugs, equipment and supplies, supportive supervision and especially adequate human resources to be trained, deliver services and supervise. This is a tall order, but alternative is bleak.

The advent of large scale donor funding of malaria control in the past six or so years began with a focus on malaria commodities. Concern was expressed to achieve coverage targets – 60% in 2005, 80% in 2010 – which was thought to be possible only if enough drugs, supplies and materials were made available to endemic countries. In this context, countries were reluctant to ‘waste’ their donor dollars and euros on health systems strengthening, human resource development and operations research. SSekabira’s efforts show these seeming peripheral elements actually provide a crucial framework without which all the malaria commodities in the world will really go to waste in storerooms and warehouses.

The use of Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) provide a simple example of the commodity vs. integrated approach. Harvey et al. reported that, “Manufacturer’s instructions like those provided with the RDTs … are insufficient to ensure safe and accurate use by CHWs. However, well-designed instructions plus training can ensure high performance.”

Training resources exist, as for example Jhpiego’s Malaria in Pregnancy Resource Package, which is freely available online. Management Sciences for Health has training tools for the procurement and supply management. Greater use of such tools is needed so that the billions of dollars and euros spent on commodities will actually save lives.

Funding &Health Systems &Human Resources Bill Brieger | 07 Aug 2007

Malaria Resource Gap

Kiszewski et al. paint a stark picture of the potential funding gaps for malaria control programming in endemic countries. Based on data available between 2000-03, the authors found that only 4.6% of approximately $1.4 billion of projected annual funding needs were available from domestic sources in African countries. With notable exceptions including Cameroon, Malawi and South Africa, most countries could contribute less than 2-3% of the total malaria programming needs, e.g. 0.1% in Kenya, 0.5% in Mozambique, 1.1% in Nigeria and 2.6% in Mali. Even if domestic contribution (which includes out-of-pocket expenditure) doubles, triples or quadruples, the gap will remain.

Obviously there are large scale donor programs addressing this gap but none can do it alone. Recently around 55% of support from the Global Fund to Fight against AIDS, TB and Malaria has gone to sub-Saharan Africa and roughly a quarter of total GFATM funding has been allocated for malaria projects. This needs to be viewed in light of the fact that $7.7 billion has been committed by GFATM over the six annual rounds of funding to date. GFATM hopes to more than double its annual commitments, but this will not meet the malaria resource gap.

The US President’s Malaria Initiative hopes to work up to a $300 million annual contribution to 15 sub-Saharan countries. The World Bank’s Malaria Booster Program is targeting specific countries with good size grants, such as $180 million for Nigeria over 5 years. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding major malaria research and expand use of existing tools. UNICEF has mobilized funds and bilateral donors to make a major contribution to meeting needs for insecticide-treated nets. NGOs in industrialized countries have been supporting this with net fund raising campaigns. An innovative taxation on air travel has brought UNITAID into the malaria arena. But is this enough?

The big challenge is sustaining funding levels. Although the GFATM is developing mechanisms for a rolling continuation of grants with good performance, grants that don’t perform or are mismanaged can be canceled. A key factor in determining performance is the strength of the health system. Kiszewski and colleagues do acknowledge that ‘program costs’ such as training, communications, monitoring and infrastructure account for 14.1% of the malaria funding needs.

The GFATM itself stresses health system strengthening (HSS) through monitoring and evaluation tools and that “funding for HSS activities can and should be applied for as part of disease components.”

Some HSS problems are deep and chronic as pointed out by MSF who has documented the health worker crises in many African countries. Therefore the question remains, will donors commit not only to addressing the malaria resource gap on a sustainable basis, but also to strengthening the underlying health system which is crucial for managing those malaria resources?

Human Resources &IPTp &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 10 Jul 2007

Build Capacity for IPTp

The August issue of Tropical Medicine and International Health demonstrates the fact that malaria control interventions do not implement themselves. Providing commodities is only part of the picture. Ouma et al. representing a team from KEMRI, JHPIEGO, CDC and the University of Amsterdam have shown that coverage of Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy is enhanced when health workers received training on focused antenatal care (FANC) and the national malaria guidelines.

“The 3-day training used a competency-based learning approach, emphasizing theory with one full day spent in a clinical setting for practical experience. The training materials included a training/orientation package of two-page laminated service provider job aids on malaria in pregnancy and FANC/MIP and community brochures.”

Ironically in Kenya there had been an IPTp policy since 1998, but without adequate staff capacity building the policy was not achieving results. The situation is similar in other countries.

An assessment for malaria in pregnancy in Akwa Ibom State in southeast Nigeria documented that two years after the national Malaria in Pregnancy Guidelines had been published (2005), front line antenatal clinic staff were not familiar with the term IPT. JHPIEGO has worked with the Federal Ministry of Health to develop the guidelines and an orientation package on FANC and MIP and is now planning to roll out MIP training for the health workers in Akwa Ibom State with support from the ExxonMobil Foundation. Hopefully this will produce similar results as the efforts in Kenya.

In conclusion, national malaria control programs and projects cannot succeed on commodities alone. Health workers need basic orientation and skills to roll back malaria