Case Management &CHW &Elimination &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 11 Apr 2018

Multilateral Initiative for Malaria (MIM) – Jhpiego Presents in Dakar

The 7th Pan African Malaria Conference holds from 15-20 April 2017, Dakar, Senegal. The conference celebrates 20 years since the initial establishment of the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM) by the Tropical Disease Research Program and partners.

The 7th Pan African Malaria Conference holds from 15-20 April 2017, Dakar, Senegal. The conference celebrates 20 years since the initial establishment of the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM) by the Tropical Disease Research Program and partners.

During the conference next week, staff from Jhpiego malaria projects in Burkina Faso, Liberia, Nepal, Madagascar and Cameroon will share oral and poster presentations to highlight their work. Below is a list along with the location numbers.

- Application d’un Audit de la Qualité des données (DQA) du paludisme dans le District Sanitaire de Kribi, Cameroun, SS-13 Oral

- Contribution des Agent de Santé Communautaire (ASC) à l’amélioration de la prévention et la prise en charge du paludisme dans le district de Kribi, Cameroun, B-40 Poster

- MOH’s effort in developing and implementing Quality Assurance plan (QAP) for Global Fund-supported antimalarial drugs: A case study of Nepal in the context of malaria elimination, C-107 Poster

- Community-Based Health Workers in Burkina Faso: Are they ready to take on a larger role to prevent malaria in pregnancy? D-115 Poster

- Contribution of Community-Based Health Workers (CBHWs) to Improving Prevention of Malaria in Pregnancy in Burkina Faso: Review of health worker perceptions from the baseline study D-118 Poster

- Malaria in Pregnancy: The Experience of MCSP in Liberia, D-140 Poster

- Improved Malaria Case Management of Under-Five Children: The Experience of MCSP-Restoration of Health Liberia project D-141 Poster

- Experiences and perceptions of care seeking for febrile illness among caregivers, pregnant women and health providers in eight districts of Madagascar D-142 Poster

Abstracts will be shared here on the day of each presentation for those unable to attend MIM. Also check Jhpiego at Exhibit Booth 148.

Abstracts will be shared here on the day of each presentation for those unable to attend MIM. Also check Jhpiego at Exhibit Booth 148.

Case Management &Severe Malaria Bill Brieger | 27 Feb 2018

The Heart of the Malaria Problem

February is Heart Month in some countries. This is a good time to explore how malaria affects the heart and cardiovascular health.

February is Heart Month in some countries. This is a good time to explore how malaria affects the heart and cardiovascular health.

In 1946 Howard Sprague observed that although “malaria is a disease from which no organ or tissue is exempt, this paper is concerned with its influence upon the circulation, and more particularly upon the heart itself.” He then outlined four ways by which this influence happens:

- its chronic and recurrent nature

- the systemic toxemia of the paroxysm

- the profound anemia produced by hemolysis and suppression of hemopoiesis

- the occlusion of capillaries and arterioles of the myocardium

Since that time other researchers have elaborated on malaria and the cardiovascular system.

Mishra et al. raise a concern that, “The role of the heart in severe malaria has not received due attention.” They point out the following:

- hypotension, shock and circulatory collapse observed in severe malaria patients

- raised cardiac enzymes in complicated malaria

- compromised microcirculation and lactic acidosis as well as excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

- Intravascular fluid depletion associated with severe malaria leading to impaired microcirculation … among others

They conclude that “Sudden cardiac deaths can also occur due to cardiac involvement,” but worry that, “It is not feasible to assess the cardiac indices in resource poor settings.”

A study by Ray and co-researchers indicated “involvement of cardiovascular system in severe malaria as evidenced from ECG and echocardiography. The study also revealed that cardiovascular instabilities are common in falciparum malaria, but can also be observed in vivax malaria.” A fatal case of imported malaria where the sole finding revealed at the postmortem evaluation was an acute lymphocytic myocarditis with myocardiolysis was described by Costenaro and colleagues.

In another example, Onwuamaegbu, Henein, and Coats reviewed the potential role of malaria in chronic and severe malaria and the connection to chronic heart failure. They concluded that, “Our review of the literature suggests that there are significant similarities in the cachexia seen in CHF and that of malaria, especially as related to the effects of muscle mass and immunology.” Clinical manifestations in P. falciparum malaria also include reduced cardiac output as was reported in an imported case of malaria by Johanna Herr and co-workers.

Marrelli and Brotto note that, “Sequestration of red blood cells, increased levels of serum creatine kinase and reduced muscle content of essential contractile proteins are some of the potential biomarkers of the damage levels of skeletal and cardiac muscles.” They explain that, “These biomarkers might be useful for prevention of complications and determining the effectiveness of interventions designed to protect cardiac and skeletal muscles from malaria-induced damage.”

Not just malaria as a disease is involved, but also the medicines used to treat it. Ngouesse and colleagues draw attention to antimalarial drugs with cardiovascular side effects. They draw particular attention to the dangers of halofantrine, quinine and quinidine, but also note mild and/or transient effects of other antimalarials.

Guidelines exist for proper and prompt malaria case management, especially protocols for caring for patients with severe malaria. These and the medicines required must be more readily available to front line health staff. And of course is we are more diligent in preventing malaria through long lasting insecticide-treated nets and other measures, our worries about severe malaria and CVD complications will reduce.

Case Management &Epidemiology &Malaria in Pregnancy Bill Brieger | 09 Dec 2017

Prof Lateef A Salako, 1935-2017, Malaria Champion

Professor Lateef Akinola Salako was an accomplished leader in malaria and health research in Nigeria whose contributions to the University of Ibadan and the Nigeria Institute for Medical Research (among others) advanced the health of the nation, the region and the world. His scientific research and his over 140 scientific publications spanned five decades.

Professor Lateef Akinola Salako was an accomplished leader in malaria and health research in Nigeria whose contributions to the University of Ibadan and the Nigeria Institute for Medical Research (among others) advanced the health of the nation, the region and the world. His scientific research and his over 140 scientific publications spanned five decades.

His research not only added to knowledge but also served as a mentoring tool to junior colleagues. Some of his vast areas of interest in malaria ranged from malaria epidemiology, to testing the efficacy of malaria drugs to tackling the problem of malaria in pregnancy. He led a team from three research sites in Nigeria that documented care seeking for children with malaria the acceptability of pre-packaged malaria and pneumonia drugs for children that could be used for community case management. Prof Salako was also involved in malaria vaccine trials and urban malaria studies.

As recent as 2013 Prof Lateef Salako, formerly of NIMR said: “It is true there is a reduction in the rate of malaria cases in the country, but to stamp out this epidemic there is the urgent need for a synergy between researchers, the government, ministries, departments and agencies and involved in malaria control. That will enable coordinated activities that will produce quicker results than what obtains at the moment.”

At least one website has been set up where people can express their condolences. As one person wrote, “Professor Lateef Salako was an exceptional student, graduating with distinction from medical school; an unforgettable teacher, speaking as a beneficiary of his tutelage; an exemplary scholar, mentoring many others; an accomplished scientist, making indelible contributions to knowledge. May his legacy endure.”

Readers are also welcome to add their own comments here about Prof Salako’s contribution to malaria and tropical health.

Case Management &Community &ITNs &Training Bill Brieger | 15 Nov 2017

Community Based Intervention in Malaria Training in Myanmar

Nu Nu Khin of Jhpiego who is working on the US PMI “Defeat Malaria Project” led by URC shares observations on the workshop being held in Yangon with national and regional/state malaria program staff to plan how to strengthen malaria interventions at the community level. The workshop has adapted Jhpiego’s Community Directed Intervention training package to the local setting.

Nu Nu Khin of Jhpiego who is working on the US PMI “Defeat Malaria Project” led by URC shares observations on the workshop being held in Yangon with national and regional/state malaria program staff to plan how to strengthen malaria interventions at the community level. The workshop has adapted Jhpiego’s Community Directed Intervention training package to the local setting.

Yesterday’s opening speech was being hailed as a significant milestone to give Community-Based Intervention (CBI) training teams the knowledge, skills, and attitudes they need to effectively provide quality malaria services and quality malaria information.

Yesterday’s opening speech was being hailed as a significant milestone to give Community-Based Intervention (CBI) training teams the knowledge, skills, and attitudes they need to effectively provide quality malaria services and quality malaria information.

This core team is going to train the critical groups of community-level implementers including CBI focal persons and malaria volunteers at the community level.

This core team is going to train the critical groups of community-level implementers including CBI focal persons and malaria volunteers at the community level.

We embarked this important step yesterday with the collaboration of Johns Hopkins University, Myanmar Ministry of Health and Sports, and World Health Organization Myanmar.

Participants will be developing action plans to apply the community approach to malaria efforts in townships and villages in three high transmission Rakhine State, Kayin State and Tanintharyi Region.

Participants will be developing action plans to apply the community approach to malaria efforts in townships and villages in three high transmission Rakhine State, Kayin State and Tanintharyi Region.

Case Management Bill Brieger | 09 Nov 2017

Contribution of the Improving Malaria Care (IMC) Project to Improving Malaria Case Management in Burkina Faso

Malaria case management including diagnosis and treatment is an essential component of malaria control and elimination. Ousmane Badolo, Mathurin Dodo, and Bonkoungou Moumouni of Jhpiego working on the USAID Improving Malaria Care Project in Burkina Faso explained at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene how they worked to improve case management by Strengthening the capacity of health care providers. There findings follow:

Malaria case management including diagnosis and treatment is an essential component of malaria control and elimination. Ousmane Badolo, Mathurin Dodo, and Bonkoungou Moumouni of Jhpiego working on the USAID Improving Malaria Care Project in Burkina Faso explained at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene how they worked to improve case management by Strengthening the capacity of health care providers. There findings follow:

Malaria kills mostly children under five and pregnant women in Burkina Faso, and is the leading reason for medical consultation and hospitalization. Improving case management is a real challenge in reducing morbidity and mortality. The goal of the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) was to reduce the morbidity by 75% by end of 2000 and malaria mortality to close to zero by the end of 2015.

Malaria kills mostly children under five and pregnant women in Burkina Faso, and is the leading reason for medical consultation and hospitalization. Improving case management is a real challenge in reducing morbidity and mortality. The goal of the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) was to reduce the morbidity by 75% by end of 2000 and malaria mortality to close to zero by the end of 2015.

The United States Agency for International Development-supported Improving Malaria Care (IMC) project aims to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality. This includes strengthening the capacity of health providers to deliver high quality management- diagnosis and treatment, of malaria cases.

The United States Agency for International Development-supported Improving Malaria Care (IMC) project aims to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality. This includes strengthening the capacity of health providers to deliver high quality management- diagnosis and treatment, of malaria cases.

Between 2014 and 2016 IMC and the NMCP revised malaria guidelines, oriented 163 national trainers, trained 1,819 providers at all levels and organized supportive supervision of these staff. As a result correct diagnostic testing of malaria cases increased from 62% to 82%.

The proportion of people with uncomplicated malaria who received artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) increased from 85% to 94%. Strengthening of the data management system facilitated this information to be collected.

The proportion of people with uncomplicated malaria who received artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) increased from 85% to 94%. Strengthening of the data management system facilitated this information to be collected.

Training these providers based on national guidelines and reinforcing their learning through supervision has enabled the NMCP to have a pool of health providers capable of treating the most vulnerable population and helping to reduce malaria mortality level in Burkina Faso.

This training is accompanied by the implementation of formative supervision. Continued supervision and quality data management positions the NMCP to reach and document its goals.

This training is accompanied by the implementation of formative supervision. Continued supervision and quality data management positions the NMCP to reach and document its goals.

Funding for this effort was provided by the United States President’s Malaria Initiative. This poster was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the Improving Malaria Care Project and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Case Management &Health Workers &IPTp &Quality of Services Bill Brieger | 08 Nov 2017

Contribution of the Standards-Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R) approach to fighting malaria in Burkina Faso

Quality improvement tools play an important role in ensuring better malaria services. Moumouni Bonkoungou, Ousmane Badolo, and Thierry Ouedraogo describe how

Jhpiego’s quality approach, Standards-Based Management and Recognition, was applied to enhancing the provision of malaria services in Burkina Faso at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. Their work was supported through the President’s Malaria Initiative and the USAID Improving Malaria Care Project.

In 2015, Burkina Faso recorded 8,286,463 malaria cases, including 450,024 severe cases with 5379 deaths. The main reasons for these death are: Inadequate application of national malaria diagnosis and treatment guidelines, delays in seeking health care and poor quality of case management.

The Standards-Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R) approach is used to improve quality of care using performance standards based on national guidelines. SBM-R includes the following steps:

- set performance standards

- implement the standards

- monitor progress and

- recognize as well as celebrate achievements

Areas or domains assessed by the approach are: services organization, case management at both health center and community, Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy (IPTp), promotion of Long Lasting Insecticide treated Nets (LLIN) use and infection prevention and control.

Areas or domains assessed by the approach are: services organization, case management at both health center and community, Intermittent Preventive Treatment in Pregnancy (IPTp), promotion of Long Lasting Insecticide treated Nets (LLIN) use and infection prevention and control.

Since June 2016, 26 health facilities in three regions have been implementing SBMR. Therefore, 105 health workers have been trained. Performance progress was measured through 5 evaluations including baseline. Baseline has shown the highest score was 47% (Kounda) while the lowest was 9% (Niangoloko).

The main issues observed were: lack of program activities, management tools, handwashing facilities, LLINs and misuse of Rapid Diagnosis Tests. Their cause was determined and an improvement plan was developed by each site. The second, third and final evaluations revealed a change in performance scores for all sites.

The external evaluation showed 17 out of 26 health facilities with a score higher than 60%; among them 10 with a score above 80% (Bougoula, 94%). At the same time, IPTp 3 increased from 34.48% in 2014 to 78.38% in 2016 and no malaria death has been registered since October 2015.

The external evaluation showed 17 out of 26 health facilities with a score higher than 60%; among them 10 with a score above 80% (Bougoula, 94%). At the same time, IPTp 3 increased from 34.48% in 2014 to 78.38% in 2016 and no malaria death has been registered since October 2015.

For the site under 80% the key reasons were: staff turnover, commodities stock-out and lack of infrastructure. The process continues with recognition of health facilities and supporting others (those at less than 80%) to reach the desired performance level. The SBM-R approach appears to be a great tool for improving quality and performance of health facilities.

Case Management &Health Workers &Training Bill Brieger | 08 Nov 2017

Health provider orientation to national malaria case management guidelines in regional hospitals in Burkina Faso

Good clinical practice in managing malaria requires awareness and understanding of national case management guidelines. Moumouni Bonkoungou, Ousmane Badolo, and Thierry Ouedraogo of Jhpiego in Collaboration with the National Malaria Control Program and sponsorship from the “Improving Malaria Care” project of USAID/PMI explain how health workers in Burkina Faso were oriented to the national guidelines at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. They have found that short orientations are less expensive and reach more health workers that traditional training sessions.

Good clinical practice in managing malaria requires awareness and understanding of national case management guidelines. Moumouni Bonkoungou, Ousmane Badolo, and Thierry Ouedraogo of Jhpiego in Collaboration with the National Malaria Control Program and sponsorship from the “Improving Malaria Care” project of USAID/PMI explain how health workers in Burkina Faso were oriented to the national guidelines at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. They have found that short orientations are less expensive and reach more health workers that traditional training sessions.

Malaria remains the leading cause of consultations, hospitalization and death in health facilities in Burkina Faso. In 2015, 23,634 cases of severe malaria were recorded in hospitals with 1,634 deaths, a mortality rate of 7% at this level compared to 1% nationally. Since April 2014, 1,819 providers from 49 districts have been trained in malaria case management, specifically at the first level (health center – CSPS). Conversely, at referral centers – medical centers with surgical units (CMA), regional hospitals (CHR) and university hospitals (CHU) – providers are not well educated on the new WHO guidelines for malaria prevention and case management.

This situation led the United States Agency for International Development-supported Improving Malaria Care (IMC) project and the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) to organize orientation sessions for providers in 8 CHR in September 2016. The sessions were conducted by trainers at the national level, supported by clinicians from hospitals including pediatricians and gynecologists.

A total of 298 health workers were oriented, including 24 physicians, 157 nurses, 56 midwives, as well as pharmacists and laboratory technicians. 39% of participants were female and 43% have less than 5 years of service in these hospitals. The sessions have provided participants with an opportunity to familiarize themselves with the new guidelines for malaria prevention and case management.

The orientations have also made it possible to identify the difficulties encountered by referral structures in malaria case management, which include: insufficient staff, inadequate capacity building, no blood bank in some hospitals, reagent stock-outs, inadequacies in the referral system, and insufficient equipment.

The orientations have also made it possible to identify the difficulties encountered by referral structures in malaria case management, which include: insufficient staff, inadequate capacity building, no blood bank in some hospitals, reagent stock-outs, inadequacies in the referral system, and insufficient equipment.

To address these difficulties, staff redeployment, internal supervision, development of tools to monitor reagents stocks have been proposed. To move forward, response plans for the period of high malaria transmission is expected to be developed for these referral facilities.

Case Management &IPTp &Quality of Services Bill Brieger | 06 Nov 2017

Implementation of a Quality Improvement Approach for Malaria Service Delivery in Zambezia Province, Mozambique

Baltazar Candrinho, Armindo Tiago, Custodio Cruz, Mercino Ombe, Katherine Wolf, Maria da Luz Vaz, Connie Lee and Rosalia Mutemba are sharing their work during a scientific session on enhancing quality of care for malaria services in Mozambique at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine 66th Annual Meeting on 6 November 2017. A summary of their talk follows:

Baltazar Candrinho, Armindo Tiago, Custodio Cruz, Mercino Ombe, Katherine Wolf, Maria da Luz Vaz, Connie Lee and Rosalia Mutemba are sharing their work during a scientific session on enhancing quality of care for malaria services in Mozambique at the 66th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Tropical Medicine 66th Annual Meeting on 6 November 2017. A summary of their talk follows:

In Mozambique, malaria in pregnancy (MIP) is one of the leading causes of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Malaria also accounts for over 40% of deaths in children less than five years old. With provincial and facility-level commitment, a simple and comprehensive quality improvement (QI) system has been established in 10 of 16 districts in Zambezia Province.

In Mozambique, malaria in pregnancy (MIP) is one of the leading causes of maternal and newborn morbidity and mortality. Malaria also accounts for over 40% of deaths in children less than five years old. With provincial and facility-level commitment, a simple and comprehensive quality improvement (QI) system has been established in 10 of 16 districts in Zambezia Province.

Since 2016, the Mozambique Ministry of Health (MOH) and Zambezia Provincial Health Directorate, in collaboration with partners, have implemented a malaria QI effort based on the Standards-Based Management and Recognition (SBM-R) approach. A standards-based approach to improving quality of malaria care engages both management and service providers to work together to assess the current performance, address gaps to ensure that all patients receive a minimum (standardized / evidence-based) package of care, and ultimately improve patient outcomes and facility performance.

Thirty-one performance standards in five content areas (MIP, Case Management, Laboratory, Pharmacy, and Management of Human Resources and Malaria Commodities) were developed and adopted by the MOH in 2016. With support from partners, 40 health workers, including managers, clinicians and lab technicians, received training on SBM-R, and facility QI teams were established.

Thirty-one performance standards in five content areas (MIP, Case Management, Laboratory, Pharmacy, and Management of Human Resources and Malaria Commodities) were developed and adopted by the MOH in 2016. With support from partners, 40 health workers, including managers, clinicians and lab technicians, received training on SBM-R, and facility QI teams were established.

These teams use checklists based on standards to conduct quarterly assessments that identify performance gaps, and then develop action plans to address areas of improvement. The MOH antenatal care and child health registers also contain information o n coverage of key malaria interventions, including IPTp, and malaria diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy and for children under five with fever.

n coverage of key malaria interventions, including IPTp, and malaria diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy and for children under five with fever.

Average attainment of standards at baseline in 20 health facilities was 30%, and is expected to improve as implementation progresses with quarterly application of the checklist (data will be available before November). Improvements in key malaria indicators for pregnant women and children under five years old are expected as the percentage of standards attained increases.

Case Management &Resistance Bill Brieger | 22 Oct 2017

The Need to Prevent the Spread of Malaria Drug Resistance to Africa

Chike Nwangwu is a Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist who is currently working on his Doctor of Public Health (DrPH) degree at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Here he presents an overview of the threat of parasite resistance to first-line antimalarial drugs and the need to prevent the spread of this problem in Africa which beard the greatest burden of the global malaria problem.

Malaria, remains one of the most pervasive and most malicious parasitic infections worldwide. Malaria is caused by Plasmodium parasites when they enter the human body. There are currently five known plasmodium species that cause malaria in humans- P. falciparum and P. vivax are the most prevalent globally. These parasites are transmitted through the bites of infected female anopheles mosquitoes “malaria-vectors” which perpetuate the spread of the parasite from human-human or from host- human.

Globally, according to the WHO, an estimated 212 million cases of malaria and 429 000 malaria related deaths occurred in 2015.[1] The global share of malaria is spread disproportionately across regions; Over 90% of global malaria cases and deaths occurred in the African region, with over 70% of the global burden in one sub region-Sub Saharan Africa. In areas with high transmission of malaria, children under 5 are at the highest risk to infection and death; more than two thirds of all malaria deaths occur in this age group.[2]

Although malaria remains a global concern, malaria is preventable and curable. Increased efforts in malaria prevention and treatment within the past two decades has led to revolutionary success- 6.8 million lives have been saved globally and malaria mortality cut by 45% since 2001.[3] Globally, within a five-year interval (2010-2015) new malaria transmission and mortality in children under 5 years of age fell by 21% and 29% respectively. This has been the one the greatest public health successes in recent years [4]

Although malaria remains a global concern, malaria is preventable and curable. Increased efforts in malaria prevention and treatment within the past two decades has led to revolutionary success- 6.8 million lives have been saved globally and malaria mortality cut by 45% since 2001.[3] Globally, within a five-year interval (2010-2015) new malaria transmission and mortality in children under 5 years of age fell by 21% and 29% respectively. This has been the one the greatest public health successes in recent years [4]

The improvement of malaria indices aligns with intensification of efforts, through funding, research, innovation pushing the scale up of key malaria interventions in the malaria prevention- diagnostic- treatment cascade. For example, in Sub-Saharan Africa where malaria is most prevalent, there has been a recorded 48% increment in Insecticide Treated Net (ITN) usage since 2005, 15% rise in chemoprevention in pregnant women and within the same time frame diagnostic testing increased from 40% of suspected malaria cases to 76%.[5]

Treatment/ Emergence of insecticide and drug resistance

Malaria treatment plays a key role in controlling its transmission. First, prompt and effective treatment of malaria prevents progression to severe disease and limits the development of gametocytes, thus blocking transmission of parasites from humans to mosquitoes.[6] Drugs can also be used to prevent malaria in endemic populations, including various strategies of chemoprophylaxis, intermittent preventive therapy, and mass drug administration can be effective.[7] Like other interventions, availability and use of antimalarial has been a success. However, this has also come with some challenges. The emergence of resistance, particularly in P. falciparum and P. vivax to antimalarial-quinine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, has been a major contributor to reported resurgences of malaria in the last three decades.[8]

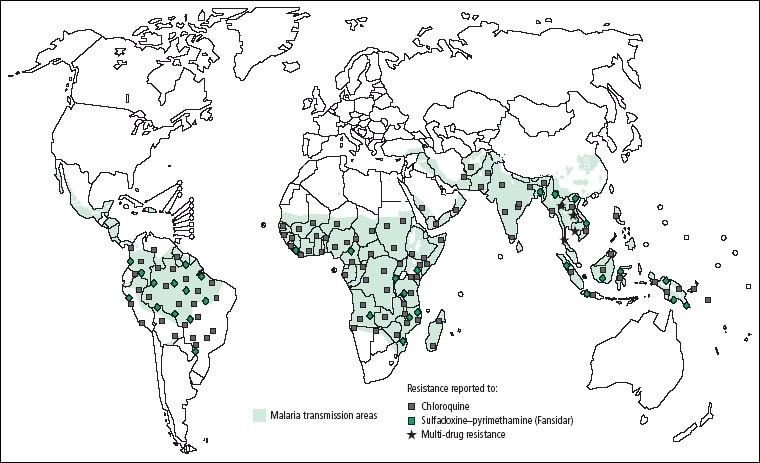

Distribution of reported resistance to antimalarials. As at 2005, antimalarial resistance was is established in 81 of the 92 countries where the disease was endemic (WHO, 2004)

Falciparum resistance first developed in some areas in Southeast Asia, Oceania, and South America before the 70’s eventually the parasite became resistant to other drugs (sulfadoxine/ pyrimethamine, mefloquine, halofantrine, and quinine. Drug-resistant P. vivax was first identified in 1989 in one region and later spread to other regions of the world.[9] As at 2005, antimalaria resistance to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine was established in 81 of the 92 countries where the disease was endemic. (Figure 1) In 2005, alongside acetaminophen, antimalarial were among the most commonly abused medications in the African region, with the majority of the population having detectable amounts of chloroquine in the blood.[10]

Antimalarial drug resistance is the decrease in viability of an antimalarial to cure an infection. Parasite resistance results in a delayed or partial clearance of parasites from the blood when a person is being treated with an antimalarial.[11] Antimalaria resistance occurs as the byproduct of at least one mutation in the genome of the parasite, giving an advantageous capacity to evade the impacts of the drug. Within the human host, drug resistance develops gradually. First, a modest number of drug-resistant parasites survive exposure to the drug whilst the drug-sensitive parasites are eliminated. In the absence of additional drugs and competition from drug-sensitive pathogens, the drug-resistant parasites proliferate and their populace develops. This new population is therefore resistant to additional malaria medications of the same type.

Following the discovery of resistance to quinine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, the development of resistance was initially forestalled by the utilization of a new class of malaria drugs – Artemisinin-derivative combinations. These ACTs (Artemisinin Combination Therapy) work by combining artemisinin and an active partner drug with different mechanisms of action. The WHO, with guidance from extensive drug efficacy tests and research, recommends the use of 5 types of ACTs for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by the P. falciparum parasite. By 2014, ACTs have been adopted as first-line treatment policy in 81 countries.[12]

Although ACT use has been a breakthrough in malaria treatment, development of resistance to de novo ACTs poses one of the greatest threats to malaria control efforts. P. falciparum resistance to artemisinin has been detected in five countries of the Greater Mekong sub-region (Lao, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam). To date P. vivax resistance to an ACT has not been detected.

Artemisinin resistance is currently defined within the confines of delayed parasite clearance; it represents partial/relative resistance-i.e. most patients who have delayed parasite clearance do not necessarily have treatment failure. Following treatment with an ACT, infections are still cleared, as long as the partner drug remains effective. Various factors are believed to contribute to the development and spread of resistance to artemisinin; use of oral artesunate monotherapies (oAMT) inclusive.

A global response has been mounted to curtail the spread of ACT resistance to other regions, especially to regions like Sub-Saharan Africa. Research on the mechanisms of drug resistance has steered efforts in the direction, recently the identification of the PfKelch13 (K13) mutations has allowed for a more refined definition of artemisinin resistance that includes information on the genotype. [13] In addition, stricter policies have been developed for malaria control; Therapeutic efficacy studies (TES) are conducted and used as the main reference from which national malaria control programmes determine their national treatment policy.[14] These studies help to ensure the efficacy of treatments with recommendations to ensure that these medicines are monitored through surveillance at least once every 24 months at established sentinel sites and in regions with emerging resistance, the creation of additional sentinel surveillance sites. [15]

A global response has been mounted to curtail the spread of ACT resistance to other regions, especially to regions like Sub-Saharan Africa. Research on the mechanisms of drug resistance has steered efforts in the direction, recently the identification of the PfKelch13 (K13) mutations has allowed for a more refined definition of artemisinin resistance that includes information on the genotype. [13] In addition, stricter policies have been developed for malaria control; Therapeutic efficacy studies (TES) are conducted and used as the main reference from which national malaria control programmes determine their national treatment policy.[14] These studies help to ensure the efficacy of treatments with recommendations to ensure that these medicines are monitored through surveillance at least once every 24 months at established sentinel sites and in regions with emerging resistance, the creation of additional sentinel surveillance sites. [15]

Preventing and containing antimalarial drug resistance- Recommendations to countries

As research is being done to fully understand the mechanisms of antimalarial resistance; basic recommendations to limit its spread have been disseminated.[16] First, the production and use of oral artemisinin-based monotherapy should be halted and access to the use of quality-assured ACTs for the treatment of falciparum malaria should be ensured. In countries where antimalarial treatments remain fully efficacious; correct medicine use must be promoted, with weight placed on encouraging diagnostic testing, quality-assured treatment, and good patient adherence to the treatment. Lastly, to reduce the burden of the disease, and prevent the spread of resistance, in regions where there is still high transmission, intensification of malaria control efforts is key, rapid elimination of falciparum malaria would accelerate efforts.

- [1] World Malaria Report 2016, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2016

- [2] ibid

- [3] CDC, Malaria Fast Facts 2017

- [4] ibid

- [5] World Malaria Report, 2016

- [6] Gosling RD, Okell L, Mosha J, Chandramohan D. The role of antimalarial treatment in the elimination of malaria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1617–1623.

- [7] Greenwood B. Anti-malarial drugs and the prevention of malaria in the population of malaria endemic areas. Malar J. 2010;9

- [8] White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1084–1092

- [9] CDC, Malaria Fast Facts, 2017

- [10] White NJ. Antimalarial drug resistance. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1084–1092.

- [11] Peter B. Bloland, Drug resistance in malaria, World Health Organization, 2001

- [12] World Malaria Report, 2016, World Health Organization, Geneva,2016

- [13] Artemisinin and artemisinin-based combination therapy resistance April 2017,World Health Organization, 2017

- [14] Responding to antimalarial drug resistance, World Health Organization, 2017: http://www.who.int/malaria/areas/drug_resistance/overview/en/

- [15] ibid

- [16] Ibid

Asia &Case Management &Diagnosis &Elimination &MDA Bill Brieger | 12 May 2017

Nepal on the Path to Malaria Elimination

Jhpiego’s Emmanuel Le Perru has been placed with Nepal’s malaria control program by the Maternal and Child Survival Program (USAID) to strengthen the agency’s overall response to malaria as well as ensure top performance of Nepal’s Global Fund Malaria grant. Emmanuel shares his experiences with us here.

From 3,000 cases in 2010, Nepal reported around 1,000 cases in 2016, including 85% Plasmodium vivax cases. However private sector reporting is almost null so number of total cases may be the double. Nepal’s National Malaria Strategic  Plan (NMSP) targets Elimination by 2022 (0 indigenous cases) with WHO certification by 2026.

Plan (NMSP) targets Elimination by 2022 (0 indigenous cases) with WHO certification by 2026.

Ward Level Micro-stratification is an important step for targeting appropriate interventions. Key interventions in the NMSP include case notification system by SMS (from health post workers or district vector control inspectors) to a Malaria Disease Information System, later to be merged with DHIS2. Case investigation teams conduct case and foci profiling as well as “passive cases” active detection and treatment (including staff from district such as surveillance coordinator, vector control inspector, and entomologist).

Malaria Mobile Clinics actively search/treat new cases in high risk areas (slums, brick factories, river villages or flooded areas, migrant workers villages, etc.). PCR diagnosis with Dry Blood Spot or Whole Blood is used to identify low density parasite cases, relapses or re-introduction. Coming up in April-June 2018 will be a Pilot of MDA (primaquine) for Plasmodium vivax in isolated settings (80% of cases in the country are P vivax).

Malaria Mobile Clinics actively search/treat new cases in high risk areas (slums, brick factories, river villages or flooded areas, migrant workers villages, etc.). PCR diagnosis with Dry Blood Spot or Whole Blood is used to identify low density parasite cases, relapses or re-introduction. Coming up in April-June 2018 will be a Pilot of MDA (primaquine) for Plasmodium vivax in isolated settings (80% of cases in the country are P vivax).

Recent successes in the national malaria effort include the number of cases notified by SMS went from 0% to 45%. Also the number of cases fully investigated went from 22% to 52%, though this needs to go up to 95% for elimination. 73% of districts are now submitting timely malaria data reports per national guidelines, an increase from 52% in November 2015.

The Global Fund (GFATM) malaria grant rating went from B2 to A2. Nepal Epidemiology Disease Control Division (EDCD), WHO and GFATM are keen to pilot MDA for P vivax in isolated setting which MCSP/Jhpiego Advisor taking the lead.

Moving forward the malaria elimination effort needs to address Indo-Nepal Cross boarder collaboration since 45% cases are imported. Hopefully WHO will help EDCD Nepal to propose a plan of action to India. The program still needs to convince partners of relevance of malaria mobile clinics vs community testing and of the relevance of MDA for P vivax. More entomological and PCR/laboratory expertise is needed. With these measures malaria elimination should be in sight.